The Role of Parents in Children’s Peer Relationships

Cliff is having a hard time…he just doesn’t have any good friends, says he has no one to do things with…he’s just not part of the gang.…I hate to see him having troubles with the other kids—I keep wondering if I should do something about it, or if he just has to sort it out hisself.…And it reminds me of my troubles at school.

(quoted in Dunn, personal communication)

The speaker, the mother of 8-year-old Cliff, not only worries about Cliff ’s problems with his peers but also feels that she may have contributed to them—a common reaction of parents of lonely and rejected children. The idea that parents influence children’s ability to relate to peers has a long history, beginning with Freud’s emphasis on the importance of the mother–child relationship as a foundation for later personality development and interpersonal relationships. Moreover, attachment theorists (see Chapter 11) as well as social learning theorists (see Chapter 9) have asserted that early parent–child interactions are linked to children’s peer interactions at an older age. It also seems likely that children’s ongoing relationships with their parents can affect their relationships with their peers.

Relations Between Attachment and Competence with Peers

Attachment theory maintains that whether a child’s attachment to the parent is secure or insecure affects the child’s future social competence and the quality of the child’s relationships with others, including peers. Attachment theorists have suggested that a secure attachment between parent and child promotes competence with peers in at least three ways (Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992). First, children with a secure attachment develop positive social expectations. They are thus inclined to interact readily with other children and expect these interactions to be positive and rewarding. Second, because of their experience with a sensitive and responsive caregiver, they develop the foundation for understanding reciprocity in relationships. Consequently, they learn to give and take in relationships and to be empathic to others. Finally, children who are securely attached are likely to be confident, enthusiastic, and emotionally positive—characteristics that are attractive to other children and that facilitate social interaction.

545

Conversely, attachment theorists argue, an insecure attachment is likely to impair a child’s competence with peers. If parents are rejecting and hostile or neglectful, young children are likely to become hostile themselves and to expect negative behavior from other people. They may be predisposed to perceive peers as hostile and, consequently, are likely to be aggressive toward them. These children may also expect rejection from other people and may try to avoid experiencing it by withdrawing from peer interaction (Furman et al., 2002; Renken et al., 1989).

There is a good deal of evidence to support these theoretical views. Children who are not securely attached do, in fact, tend to have difficulties with peer relationships. Toddlers and preschoolers who were insecurely attached as infants tend to be aggressive, whiny, socially withdrawn, and low in popularity in elementary school (Bohlin, Hagekull, & Rydell, 2000; Burgess et al., 2003; Erickson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 1985). Throughout childhood, these children, in comparison with securely attached children, express less positive emotion with peers, as well as less sympathy and prosocial behavior, and they demonstrate poorer skills in resolving conflicts (Elicker et al., 1992; Fox & Calkins, 1993; Kestenbaum, Farber, & Sroufe, 1989; Panfile & Laible, 2012; Raikes & Thompson, 2008).

Securely attached children, on the other hand, tend to exhibit positive emotions and good social skills and, not surprisingly, tend to have high-quality friendships and to be relatively popular with peers—both as preschoolers (LaFreniere & Sroufe, 1985; McElwain, Booth-LaForce, & Wu, 2011) and in elementary school and adolescence (Granot & Mayseless, 2001; Kerns, Klepac, & Cole, 1996; B. H. Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001; see Chapter 11). Even in late childhood and early adolescence, children with more and higher-quality (e.g., more intimate and supportive) friendships tend to be those with a history of a secure attachment (Dwyer et al., 2010; Freitag et al., 1996; B. H. Schneider et al., 2001; J. A. Simpson et al., 2007). Some recent research suggests that the security of attachment with fathers may be especially important for the quality of children’s and adolescents’ friendships (e.g., Doyle, Lawford, & Markiewicz, 2009; Verissimo et al., 2011).

Thus, security of the parent–child relationship is linked with quality of peer relationships. This link probably arises from both the early and the continuing effect that parent–child attachment has on the quality of social behavior, as well as their working models of relationships (Shomaker & Furman, 2009). However, it is also possible that the individual characteristics of each child, such as sociability, influence both the quality of attachments and the quality of his or her relationships with peers.

Quality of Ongoing Parent–Child Interactions and Peer Relationships

Ongoing parent–child interactions are associated with peer relations in much the same way that attachment patterns are. For example, socially competent, popular children tend to have mothers who are warm in general, discuss feelings with them, and who use warm control, positive verbalizations, reasoning, and explanations in their approach to parenting (C. H. Hart et al., 1992; Kam et al., 2011; McDowell & Parke, 2009; Updegraff et al., 2010). Research that has investigated ongoing father–child interactions has found that they, too, can play a role in children’s peer relationships. For example, fathers’ warmth and expression of positive rather than negative emotion with their children has been linked to the positivity of children’s interactions with close friends in the preschool years (Kahen, Katz, & Gottman, 1994; Youngblade & Belsky, 1992) and to children’s peer acceptance in elementary school (McDowell & Parke, 2009).

546

Overall, research in this area suggests that when the family is generally characterized by a warm, involved, and harmonious family style, young children tend to be sociable, socially skilled, liked by peers, and cooperative in child care (R. Feldman & Masalha, 2010). These associations may occur because such parenting fosters children’s self-regulation (Eiden et al., 2009; N. Eisenberg, Zhou et al., 2005; Kam et al., 2011). In contrast, parenting that is characterized by harsh, authoritarian discipline and low levels of child monitoring is often associated with children’s being unpopular and victimized (Dishion, 1990; Duong et al., 2009; C. H. Hart, Ladd, & Burleson, 1990; Ladd, 1992).

In considering findings such as these, it is generally assumed that quality of parenting influences the degree to which children behave in socially competent ways, which in turn affects whether children are accepted by peers. But as in the case of attachment, it is difficult to prove that quality of parenting actually has a causal influence on children’s social behavior with peers. As we noted in Chapter 12, it may be that children who are aggressive and disruptive because of constitutional factors (e.g., heredity, prenatal influences) elicit both negative parenting and negative peer responses (Rubin et al., 1998); or it may be that both harsh parenting and the children’s negative behavior with peers are due to heredity. The most likely possibility is that the causal links are bidirectional—that parents’ behavior affects their children’s social competence and vice versa—and that both environmental and biological factors play a role in the development of children’s social competence with peers.

Parental Beliefs

Parents of socially competent children think about parenting and their children somewhat differently than do parents of children who have low social competence. For one thing, they are more likely to believe that they should play an active role in teaching their children social skills and in providing them with opportunities for peer interaction. They also tend to believe that when their children display inappropriate or maladaptive behavior with a peer (e.g., aggression, hostility, social withdrawal), it is because of the circumstances of the specific situation, such as a provocation by the peer or a mutual misunderstanding. In contrast, parents of less socially competent children tend to believe that when their children behave in socially inappropriate ways, it is because of something in their children’s nature and that it would thus be very hard to alter such behavior (Rubin et al., 2006). In other words, they tend to believe that their children “were born that way.” Of course, it is difficult to know the degree to which parents’ beliefs about their children’s social competencies are based on realistic perceptions of their offspring or on their own belief systems and personal history (such as the troubles Cliff ’s mother experienced when she was a schoolchild).

Gatekeeping and Coaching

Other dimensions of parent–child interactions may influence children’s competencies in peer relationships. Two of the more salient ones are parents’ gatekeeping role in their children’s social life and their coaching of their children in social skills.

547

Gatekeeping

As noted in Chapter 12, parents, especially those of young children, act as gatekeepers, controlling where their children go, with whom they interact, and how much time they spend with peers doing various activities. However, some parents are more thoughtful and active in this role than are others (Mounts, 2002). Preschoolers whose parents arrange and oversee opportunities for them to interact with peers tend to be more positive and social with peers, have a larger and more stable set of play partners, and more easily initiate social interactions with peers than do other children—so long as their parents are not overly controlling in this gatekeeping role (Ladd & Golter, 1988; Ladd & Hart, 1992). Similarly, elementary school children whose parents allow them to engage in numerous social activities in the neighborhood and extracurricular activities at school are more socially competent and liked by peers (McDowell & Parke, 2009).

In adolescence, gatekeeping may be affected by parents’ cultural orientation. For example, in Mexican American families, parents who had a stronger orientation toward Mexican culture and the traditional Mexican value of familism—which emphasizes closeness in the family, family obligations, and consideration of the family in making decisions—placed more restrictions on adolescents’ peer relationships than did parents whose orientation was less traditional. They were also more likely to restrict their adolescents’—especially a daughter’s—contact with peers if the adolescent reported associating with deviant peers (Updegraff et al., 2010).

Coaching

Preschool children tend to be more socially skilled and more likely to be accepted by peers if their parents effectively coach them on how to interact with unfamiliar peers (Laird et al., 1994; McDowell & Parke, 2009). Mothers of accepted children tend to teach their children group-oriented strategies for gaining entry into a group of peers: they may make suggestions about what to say when entering the group, for example, or they may discourage the child from disrupting the group’s current activities. In contrast, mothers of children who are low in sociometric status often try to direct the group’s activity themselves or urge their child to initiate activities that are inconsistent with what the group is currently doing (Finnie & Russell, 1988; A. Russell & Finnie, 1990).

548

Children may also benefit in their peer relations when their parents provide emotion coaching—that is, explanations about the acceptability of emotions and how to appropriately deal with them (L. F. Katz, Maliken, & Stettler, 2012). Children whose parents use high levels of emotion coaching are, for example, more likely to use appropriate conflict-avoidance strategies, such as laughter, to deflect teasing, and they are less likely to display socially inappropriate behaviors when dealing with peers’ provocations (L. F. Katz, Hunter, & Klowden, 2008). Some evidence suggests that a fairly high level of parental advice giving is sometimes associated with low levels of children’s social competence and peer acceptance; but, in part, this may be because parents are more likely to try to help when their children are experiencing a high level of problems (McDowell & Parke, 2009). It is likely that coaching needs to be provided in a sensitive, skilled manner to be effective; that is, it should convey clear, useful information about others’ feelings and behavior, along with strategies for dealing with them, and it should be presented in a way that does not overwhelm children or derogate them. For reasons that are not yet clear, mothers’ coaching may be especially important for enhancing girls’ social skills (Pettit et al., 1998).

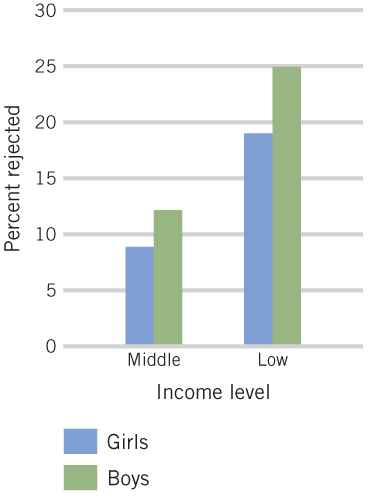

Family Stress and Children’s Social Competence

As discussed in Chapter 12, parents who are preoccupied and distressed by problems related to poverty are more likely to be negative and less likely to be warm and supportive and to monitor their children’s behavior (Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, 2007; McLoyd, 1998). Thus, it is not surprising that children from families with fewer economic resources and higher levels of stress (e.g., unemployment, health problems) exhibit less social competence, have fewer friends, and are more likely than other children to be rejected by their peers (Brophy-Herb et al., 2007; Criss et al., 2002; Dishion, 1990; C. J. Patterson et al., 1992). For example, in a longitudinal study, elementary school children from low-income families were considerably more likely to be rejected than were children from middle-class families (boys also were rejected more than girls; see Figure 13.5). It is likely that the effects of poverty and stress on parenting are reflected in children’s compromised social competence.

review:

Although differences in children’s social behavior likely are based in part on constitutional factors that influence temperament and personality, parents appear to influence children’s competence with peers. Attachment theorists have suggested that a secure attachment between parent and child promotes peer competence because securely attached children develop positive social expectations, the foundation for understanding reciprocity in relationships, and a sense of self-worth and self-efficacy. In fact, securely attached children tend to be more positive in their behavior and affect, more socially skilled, and better liked than insecurely attached children. Ongoing parent–child interactions show similar associations with peer relations.

549

Parents can also influence their children’s competence with peers through their beliefs, their role as gatekeepers, and the social behaviors they teach their children. It is probable that the causal links between quality of parenting and children’s social competence are bidirectional and that both environmental (e.g., parenting, poverty) and biological factors play a role in the development of children’s social competence with peers.