Friendships

Kay and Sarah are my best friends—we talk and share secret things…and we sometimes do things with Jo and Kerry and Sue. Then there’s all the rest of the girls—some are nice. But the boys—yuk!

(Annie, aged 8, cited by Dunn, personal communication, 1999)

friendship  an intimate, reciprocated positive relationship between two people

an intimate, reciprocated positive relationship between two people

Annie, the speaker above, clearly differentiates her close friends from other children she knows and with whom she may also interact. Researchers generally agree that friends are people who like to spend time together and feel affection for one another. In addition, their interactions are characterized by reciprocities; that is, friends have mutual regard for one another, exhibit give-and-take in their behavior (such as cooperation and negotiation), and benefit in comparable ways from their social exchanges (Bukowski, Newcomb, & Hartup, 1996). In brief, a friendship is an intimate, reciprocated positive relationship between two people. As we will discuss next, the degree to which the conditions of friendship become evident in peer interactions increases with age during childhood.

Early Peer Interactions and Friendships

Very young children usually cannot verbally indicate who they like, so researchers must make inferences about children’s friendships from observing their behavior with peers. In doing so, researchers have focused particularly on such issues as the age at which friendships first develop, the nature of early friendships, and age-related changes in friendships.

Do Very Young Children Have Friends?

Some investigators have argued that children can have friends by or before the age of 2 (C. Howes, 1996). Consider the following example:

Anna and Suzanne are not yet 2 years old. Their mothers became acquainted during their pregnancies and from their earliest weeks of life the little girls have visited each other’s houses. When the girls were 5 months old they were enrolled in the same child-care center. They now are frequent play partners, and sometimes insist that their naptime cots be placed side by side. Their greetings and play are often marked by shared smiles. Anna and Suzanne’s parents and teachers identify them as friends.

(C. Howes, 1996, p. 66)

514

Even 12- to 18-month-olds seem to select and prefer some children over others, touching them, smiling at them, and engaging in positive interactions with them more than they do with other peers (D. F. Hay, Caplan, & Nash, 2009; C. Howes, 1983; Shin, 2010). In addition, when a preferred peer shows distress, toddlers are three times more likely to respond by offering comfort or by alerting an adult than they are when a nonpreferred peer is upset (C. Howes & Farver, 1987). Starting at around 20 months of age, children also increasingly initiate more interactions with some children than with others and contribute more when playing games with those children (H. S. Ross & Lollis, 1989). By age 3 or 4, children can make and maintain friendships with peers (Dunn, 2004), and most have at least one friendship (M. Quinn & Hennessy, 2010). By age 3 to 7 years, it is not uncommon for children to have “best friends” who retain that status over at least several months’ time (Sebanc et al., 2007).

Differences in Young Children’s Interactions with Friends and Nonfriends

By the age of 2, children begin to develop several skills that allow greater complexity in their social interactions, including imitating peers’ and other people’s social behavior (Seehagen & Herbert, 2011), engaging in cooperative problem solving, and trading roles during play (C. A. Brownell, Ramani, & Zerwas, 2006; C. Howes, 1996; C. Howes & Matheson, 1992). These more complex skills tend to be in greater evidence in the play of friends than of nonfriends (acquaintances) (Werebe & Baudonniere, 1991).

Especially with friends, cooperation and coordination in children’s interactions continue to increase substantially from the toddler to the preschool years (C. Howes & Phillipsen, 1998). This is especially evident in shared pretend play (Dunn, 2004), which occurs more often among friends than among nonfriends (C. Howes & Unger, 1989). As discussed in Chapter 7, pretend play involves symbolic actions that must be mutually understood by the play partners, as in the following example:

Johnny, 30 months, joins his friend Kevin who is pretending to go on a picnic. Johnny, on instruction from 3-year-old Kevin, fills the car with gas, “drives” the car, then gets the food out, pretends to eat it, saying he doesn’t like it! Both boys pretend to spit out the food, saying “yuk!,” laughing.…

(Dunn, personal communication, 1999)

Pretend play may occur more often among friends because friends’ experiences with one another allow them to trust that their partner will work to interpret and share the meaning of symbolic actions (C. Howes, 1996). The degree to which preschoolers engage in, and are competent at, such pretend play is related to their prosocial behaviors such as kindness, cooperation, sharing, and empathy (Spivak & Howes, 2011).

While the rate of cooperation and positive interactions among young friends is higher than among nonfriends, so is the rate of conflict. Preschool friends quarrel as much or more with one another as do nonfriends and also more often express hostility by means of assaults, threats, and refusing requests (Fabes et al., 1996; D. C. French et al., 2005; Hartup et al., 1988). The higher rate of conflict for friends is likely due, in part, to the greater amount of time friends spend together.

Although preschool friends are more likely than nonfriends to fight, they also are more likely to resolve conflicts in controlled ways, such as by negotiating, asserting themselves nonaggressively, acquiescing, or simply ceasing the activity that is causing the conflict (Fabes et al., 1996; Hartup et al., 1988) (see Table 13.1). Moreover, friends are more likely than nonfriends to resolve conflicts in ways that result in equal outcomes rather than in one child’s winning and another’s losing. Thus, after a conflict, friends are more likely than nonfriends to resume their interactions and to have positive feelings for one another.

515

Developmental Changes in Friendship

In the school years, many of the patterns apparent in the interactions among preschool-aged friends and nonfriends persist and become more sharply defined. As earlier, friends, in comparison with nonfriends, communicate more and better with one another and cooperate and work together more effectively (Hartup, 1996). They also fight more often—but again, they are also more likely to negotiate their way out of the conflict (Laursen, Finkelstein, & Betts, 2001). In addition, they now have the maturity to take responsibility for the conflict and to give reasons for their disagreement, increasing the likelihood of their maintaining the friendship (Fonzi et al., 1997; Hartup et al., 1993; Whitesell & Harter, 1996).

Although children’s friendships remain similar in many aspects as the children grow older, they do change in one important dimension: the level and importance of intimacy. The change is reflected both in the nature of friends’ interactions with one another and in the way children conceive of friendship. Between ages 6 and 8, for example, children define friendship primarily on the basis of actual activities with their peers and tend to define “best” friends as peers with whom they play all the time and share everything (Gummerum & Keller, 2008; Youniss, 1980). At this age, children also tend to view friends in terms of rewards and costs (Bigelow, 1977). In this respect, friends tend to be close by, have interesting toys, and have similar expectations about play activities. Nonfriends tend to be uninteresting or difficult to get along with. Thus, in the early school years, children’s views of friendship are instrumental and concrete (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006) (see Table 13.2).

In contrast, between the early school years and adolescence, children in both Asian and Western countries increasingly define their friendships in terms of characteristics such as companionship, similarity in attitudes/interests, acceptance, trust, genuineness, mutual admiration, and loyalty (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Gummerum & Keller, 2008; McDougall & Hymel, 2007). At about 9 years of age, children seem to become more sensitive to the needs of others and to the inequalities among people. Children define friends in terms of taking care of one another’s physical and material needs, providing general assistance and help with school work, reducing loneliness and the sense of being excluded, and sharing feelings. The following descriptions of friends are typical:

female, 10: If you’re hurt, they come over and visit.

male, 9: Help someone out. If the person is stuck, show them the answer but tell them why it’s the answer.

male, 9: You’re lonely and your friend on a bike joins you. You feel a lot better because he joined you.

(Youniss, 1980, pp. 177–178)

516

When children are about 10 years old, loyalty, mutual understanding, and self-disclosure become important components of children’s conceptions of friendship (Bigelow, 1977). In addition, both preadolescents and adolescents emphasize cooperative reciprocity (doing the same things for one another), equality, and trust between friends (Youniss, 1980). The following descriptions are indicative of how children in this age range view their friends:

female, 10: Somebody you can keep your secrets with together. Two people who are really good to each other.

male, 12: A person you can trust and confide in. Tell them what you feel and you can be yourself with them.

female, 13: They’ll understand your problems. They won’t always be the boss. Sometimes they’ll let you decide; they’ll take turns. If you did something wrong, they’ll share the responsibility.

male, 14: They have something in common. You hang around with him.…We’re more or less the same; the same personalities.

(Youniss, 1980, pp. 180–182)

More than younger children, adolescents use friendship as a context for self-exploration and working out personal problems (Gottman & Mettetal, 1986). Thus, friendships become an increasing source of intimacy and disclosure with age, as well as a source of honest feedback. These changes may explain why adolescents perceive the quality of their friendships as improving from middle to late adolescence and why they value them so highly (Way & Greene, 2006).

What accounts for the various age-related changes that occur in children’s friendships, particularly with regard to their concept of friendship? Some researchers have argued that the changes in children’s thinking about friendship are qualitative, or discontinuous. For example, Selman (1980) suggested that changes in children’s reasoning about friendships are a consequence of age-related qualitative changes in their ability to take others’ perspectives (see Chapter 9). In the view of Selman, as well as of Piaget and others, young children have limited awareness that others may feel or think about things differently than they themselves do. Consequently, their thinking about friendships is limited in the degree to which they consider issues beyond their own needs. As children begin to understand others’ thoughts and feelings, they realize that friendships involve consideration of both parties’ needs so that the relationship is mutually satisfying.

517

Other researchers argue that the age-related changes in children’s conceptions of friendships reflect differences in how children think and express their ideas rather than age-related differences in the basic way they view friendships. Hartup and Stevens (1997) maintain that children of all ages consider their friendships “to be marked by reciprocity and mutuality—the giving and taking, and returning in kind or degree” (p. 356). What differs with age is merely the complexity with which children view friendship and describe its dimensions. Nonetheless, these differences likely have important effects on children’s behavior with friends and on their reactions to friends’ behavior. For example, because 6th-graders are more likely than 2nd-graders to report that intimacy and support are important features of friendships (Furman & Bierman, 1984), they are more likely to evaluate their own and their friends’ behaviors in terms of these dimensions.

The Functions of Friendships

As is clear from their statements about the meaning of friendships, having friends provides numerous potential benefits for children. The most important of these, noted by Piaget, Vygotsky, and others, are emotional support and the validation of one’s own thoughts, feelings, and worth, as well as opportunities for the development of important social and cognitive skills.

Support and Validation

Friends can provide a source of emotional support and security, even at an early age. Consider the following fantasy play interaction between Eric and Naomi, two 4-year-olds who have been best friends for some time. In the course of their play, Eric expresses his ongoing fear that other children don’t like him and think he’s stupid:

Eric: I’m the skeleton! Whoa! [screams] A skeleton, everyone! A skeleton!

Naomi: I’m our friend, the dinosaur.

Eric: Oh, hi Dinosaur. [subdued] You know, no one likes me.

Naomi: [reassuringly] But I like you. I’m your friend.

Eric: But none of my other friends like me. They don’t like my new suit. They don’t like my skeleton suit. It’s really just me. They think I’m a dumb-dumb.

Naomi: I know what. He’s a good skeleton.

Eric: [yelling] I am not a dumb-dumb!

Naomi: I’m not calling you a dumb-dumb. I’m calling you a friendly skeleton.

(Parker & Gottman, 1989, p. 95)

In this fantasy play situation, Naomi clearly served as a source of support and validation for Eric. When he expressed concern that others do not like him, she reassured him that she does. And when he confessed that the other children think he, not the skeleton, is dumb, she shifted the focus from him to the fantasy skeleton character, praising the skeleton character to make Eric feel competent (“He’s a good skeleton”) (Gottman, 1986).

518

Friends also can provide support when a child feels lonely. School-aged children with best friends and with intimate, supportive friendships experience less loneliness compared with children who do not have a best friend or whose friends are less caring and intimate (Asher & Paquette, 2003; Erdley et al., 2001; Kingery, Erdley, & Marshall, 2011). Correspondingly, chronic friendlessness predicts internalizing problems such as depression and social withdrawal, which often cause or accompany loneliness (Engle, McElwain, & Lasky, 2011; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003; Palmen et al., 2011; S. Pedersen et al., 2007).

The support of friends can be particularly important during difficult periods of transition that involve peers. For example, young children have more positive initial attitudes toward school if they begin school with a large number of established friends as classmates (Ladd & Coleman, 1997; Ladd & Kochenderfer, 1996). In part, this may be because the presence of established friends in the early weeks of school reduces the strangeness of the new environment. Similarly, as 6th-graders move into junior high, they are more likely to increase their levels of sociability and leadership if they have stable, high-quality, intimate friendships during this period (Berndt, Hawkins, & Jiao, 1999).

Friendships may also serve as a buffer against unpleasant experiences, such as being yelled at by the teacher, being excluded or victimized by peers (Bukowski, Laursen, & Hoza, 2010; Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1996; Waldrip, Malcolm, & Jensen-Campbell, 2008), or being socially isolated (i.e., having low levels of involvement with peers more generally; Laursen et al., 2007). In one study that demonstrated this effect, 5th- and 6th-graders reported on their negative experiences over a 4-day period, indicating shortly after each such experience how they felt about themselves and whether or not a best friend had been present during each experience. The researchers also recorded the children’s cortisol levels multiple times each day, as a measure of the children’s stress reactions. The study showed that when a best friend was not present, the more negative children’s everyday experiences were, the greater the increase in their cortisol levels and the greater the decline in their sense of self-worth following each experience (R. E. Adams, Santo, & Bukowski, 2011). In contrast, when a best friend was present, there was less change in cortisol responding and in the child’s self-worth due to negative experiences.

This buffering effect of friends is especially clear for victimized children. Victimized children fare better if they have a number of reciprocated friendships (Hodges et al., 1999; D. Schwartz et al., 1999), if their friends are capable of defending them and are liked by peers (Hodges et al., 1997), and if their friendships are of high quality—that is, are perceived as providing intimacy, security, and help when needed (Kawabata, Crick, & Hamaguchi, 2010; M. E. Schmidt & Bagwell, 2007).

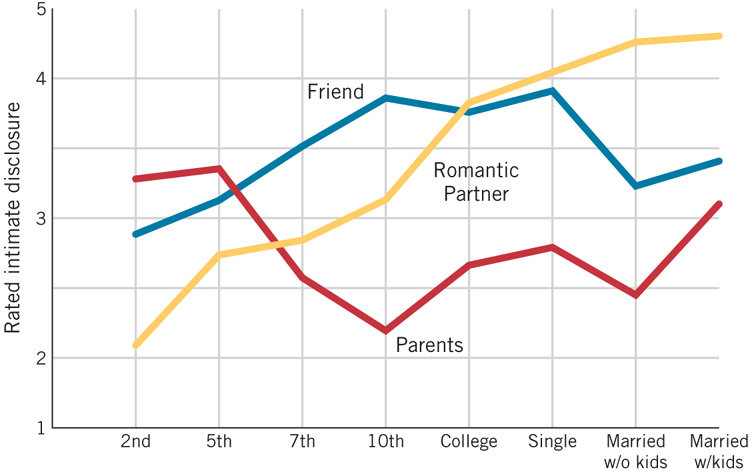

As noted previously, the degree to which friends provide caring and support generally increases from childhood into adolescence (De Goede, Branje, & Meeus, 2009). Indeed, around age 16, adolescents, especially girls, report that friends are more important confidantes and providers of support than their parents are (Bokhorst, Sumter, & Westenberg, 2010; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000; Hunter & Youniss, 1982) (Figure 13.1).

519

The Development of Social and Cognitive Skills

Friendships provide a context for the development of social skills and knowledge that children need to form positive relationships with other people. As discussed earlier, young children seem to first develop more complex play in interactions with friends; and throughout childhood, cooperation, negotiation, and the like are all more common among friends than among nonfriends. In addition, young children who discuss emotions with their friends and interact with them in positive ways develop a better understanding of others’ mental and emotional states than do children whose peer relationships are less close (C. Hughes & Dunn, 1998; Maguire & Dunn, 1997). These skills can be brought to bear when helping their friends. In a study of 3rd- to 9th-graders over the course of the school year, those with high-quality friendships improved in the quality of their reported strategies for helping friends deal with social stressors. For example, they reported becoming more likely to be emotionally engaged in talking with their friend about a problem and less likely to act as though the problem did not exist (Glick & Rose, 2011).

Friendship provides other avenues to social and cognitive development as well. Through gossip with friends about other children, for example, children learn about peer norms, including how, why, and when to display or control the expression of emotions and other behaviors (Gottman, 1986; McDonald et al., 2007). As Piaget pointed out, friends are more likely than nonfriends to criticize and elaborate on one another’s ideas and to elaborate and clarify their own ideas (Azmitia & Montgomery, 1993; J. Nelson & Aboud, 1985).

This kind of openness promotes cognitive skills and enhances performance on creative tasks (Miell, 2000; Rubin et al., 2006). One demonstration of this was provided by a study in which teams of 10-year-olds, half of them made up of friends and the other half made up of nonfriends, were assigned to write a story about rain forests. The teams consisting of friends engaged in more constructive conversations (e.g., they posed alternative approaches and provided elaborations more frequently) and were more focused on the task than were teams of nonfriends. In addition, the stories written by friends were of higher quality than those written by nonfriends (Hartup, 1996).

Gender Differences in the Functions of Friendships

As children grow older, gender differences emerge in what girls and boys feel they want and get from their friendships. Girls are more likely than boys to desire closeness and dependency in friendships and also to worry about abandonment, loneliness, hurting others, peers’ evaluations, and loss of relationships if they express anger (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). By late elementary school, girls, compared with boys, feel that their friendships are more intimate and provide more validation, caring, help, and guidance (Bauminger et al., 2008; A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006; Zarbatany, McDougall, & Hymel, 2000). For instance, girls are more likely than boys to report that they rely on their friends for advice or help with homework, that they and their friends share confidences and stick up for one another, and that their friends tell them that they are good at things and make them feel special.

Probably as a consequence of this intimacy, girls also report getting more upset than do boys when friends betray them, are unreliable, or do not provide support and help (MacEvoy & Asher, 2012). Girls also report more friendship-related stress, such as when a friend breaks off a friendship or reveals their secrets or problems to other friends, and greater stress from dealing emotionally with stressors that their friends experience (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Ironically, the very intimacy of girls’ close friendships may make them more fragile, and therefore of shorter duration, than those of boys (Benenson & Christakos, 2003; A. Chan & Poulin, 2007; C. L. Hardy, Bukowski, & Sippola 2002).

520

As discussed in Chapter 10, girls are also more likely than boys to co-ruminate with their close friends, that is, to extensively discuss problems and negative thoughts and feelings (R. L. Smith & Rose, 2011). And compared with their male counterparts, girls who are socially anxious or depressed seem more susceptible to the anxiety or depression of their friends (Giletta et al., 2011; M. H. van Zalk et al., 2010; N. van Zalk et al., 2011). Unfortunately, while providing support, a co-ruminating anxious or depressed friend may also reinforce the other friend’s anxiety or depression, especially in young adolescent girls (A. J. Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007; Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2012).

Girls and boys are less likely to differ in the amount of conflict they experience in their best friendships (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Boys’ and girls’ friendships also do not differ much in terms of the recreational opportunities they provide (e.g., doing things together, going to one another’s house) (Parker & Asher, 1993), although they often differ in the time spent together in various activities (e.g., sports versus shopping; A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006).

Effects of Friendships on Psychological Functioning and Behavior over Time

Because friendships fill important needs for children, it might be expected that having friends enhances children’s social and emotional health. In fact, having close, reciprocated friendships in elementary school has been linked to a variety of positive psychological and behavioral outcomes for children, not only during the school years but also years later in early adulthood. However, there also may be costs to having friends, if the friends engage in or encourage negative behaviors rather than positive ones (Simpkins, Eccles, & Becnel, 2008).

The Possible Long-Term Benefits of Having Friends

Longitudinal research provides the best data concerning the possible long-term benefits of having friends in elementary school. Because this research is generally correlational, however, it is difficult to determine if having friends influences long-term outcomes such as psychological adjustment, or if characteristics of the child (such as psychological adjustment) affect whether the child has friends (Klima & Repetti, 2008).

reciprocated best friendship  a friendship in which two children view each other as best or close friends

a friendship in which two children view each other as best or close friends

Typical of this research is a study that examined the relation between the quality of friendship and the development of aggression. In this study, researchers followed children from kindergarten to 2nd grade and found that children with high-quality friendships became less physically aggressive over time (Salvas et al., 2011). In another, broader, longitudinal study, researchers looked at children when they were 5th-graders and when they were young adults. They found that, compared with their peers who did not have reciprocated best friendships, 5th-graders who did have them were viewed by classmates as more mature and competent, less aggressive, and more socially prominent (e.g., they were liked by everyone or were picked for such positions as class president or team captain). At approximately age 23, those individuals who had reciprocated best friendships in 5th grade reported higher levels of doing well in college and in their family and social life than did individuals who did not have a reciprocated best friendship. They also reported higher levels of self-esteem, fewer problems with the law, and less psychopathology (e.g., depression) (Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, 1998). Thus, having a reciprocated best friendship in preadolescence relates not only to positive social outcomes in middle childhood but also to self-perceived competence and adjustment in adulthood.

521

The Possible Costs of Friendships

Although friendships are usually associated with positive outcomes, sometimes they are not. Friends who have behavioral problems may exert a detrimental influence, contributing to the likelihood of a child’s or adolescent’s engaging in violence, drug use, or other negative behaviors. And as previously noted, friends who are depressed may foster depression in their close friends, in part through a contagion effect (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011).

Aggression and disruptiveness

In the elementary school years and early adolescence, children who have antisocial and aggressive friends tend to exhibit antisocial, delinquent, and aggressive tendencies themselves, even across time (Brendgen, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 2000; J. Snyder et al., 2008). However, the research in this area is correlational, so it is difficult to know to what degree this pattern reflects socialization or individual selection. With regard to individual selection, aggressive and disruptive children may gravitate toward peers who are similar to themselves in temperament, preferred activities, or attitudes, thereby taking an active role in creating their own peer group (Knecht et al., 2010; Mrug, Hoza, & Bukowski, 2004). At the same time, friends appear to affect one another’s behavior (Vitaro, Pedersen, & Brendgen, 2007). Through their talk and behavior, youths who are antisocial may socialize and reinforce aggression and deviance in one another by making these behaviors seem acceptable (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011; Piehler & Dishion, 2007). This pattern is more likely to occur with those adolescents who are easily influenced by peers holding high status in the peer group (Prinstein, Brechwald, & Cohen, 2011) or by friends whose peer-group status is higher than their own (Laursen et al., 2012).

The factors accounting for the association between friends’ antisocial behavior may change with age. One longitudinal study found that both selection and socialization processes were in play in mid-adolescence, but that from ages 16 to 20, antisocial behavior was reinforced only through socialization by friends. After age 20, an age past which youths become more resistant to peer influence, there was little evidence of either process occurring (Monahan, Steinberg, & Cauffman, 2009).

Alcohol and substance abuse

As in the case of aggression, adolescents who abuse alcohol or drugs tend to have friends who do so also (Jaccard, Blanton, & Dodge, 2005; Scholte et al., 2008; Urberg, Değirmencioğlu, & Pilgrim 1997). And again, as in the case of aggression, it is not clear if friends’ substance abuse is a cause or merely a correlate of adolescents’ substance abuse, or if the relation between the two is bidirectional.

On the one hand, there is some evidence that adolescents tend to select friends who are similar to themselves in terms of drinking and the use of drugs (Knecht et al., 2011), and this may be especially true for those youths who are highly susceptible to peer pressure (Schulenberg et al., 1999). However, there is also evidence that peer socialization influences drug and alcohol use (Branstetter, Low, & Furman, 2011). For example, adolescents who start drinking or smoking tend to have a close friend who has been using alcohol or tobacco (Selfhout, Branje, & Meeus, 2008; Urberg et al., 1997). Youths who are highly susceptible to the influence of their close friends seem particularly vulnerable to any pressure from them to use drugs and alcohol (Allen, Porter, & McFarland, 2006), and, as in the case of aggression, this is especially the case if those friends have high status in the peer group (Allen et al., 2012). There is also evidence that adolescents’ use of alcohol and drugs and their friend’s alcohol and substance use mutually reinforce each other, often resulting in an escalation of use (Bray et al., 2003; Popp et al., 2008; Poulin et al., 2011).

522

Yet another factor in the association between adolescents’ abuse of drugs and alcohol and that of their friends is their genetic makeup. Youths with similar genetically based temperamental characteristics such as risk-taking may be drawn both to one another and to alcohol or drugs (Dick et al., 2007; J. Hill et al., 2008). Thus, friends’ alcohol and drug abuse may be correlated because of their similarity in genetically based characteristics as well as in their socialization experiences, although the effect of a group of friends on youths’ drinking is not due solely to genetics (Cruz, Emery, & Turkheimer, 2012).

Box 13.1: individual differences

Culture and Children’s Peer Experience

Young children’s contact with unrelated peers varies considerably around the world. In some communities, such as one in Okinawa, Japan, Beatrice Whiting and Carolyn Edwards (1988) found that children were free to wander in the streets and public areas of town and had extensive contact with peers. In contrast, in some sub-Saharan African societies, children were confined primarily to the family yard and therefore had relatively little contact with peers other than their siblings.

As might be expected, Whiting and Edwards found that children’s access to the wider community, including peers, increased with age. However, even when children were aged 6 to 10, there were marked differences in the extent to which their social interactions extended beyond the family. In large measure, these differences were based on parents’ attitudes toward childhood peer relationships. For example, in kin-based societies such as Kenya, peer interactions were discouraged:

Parents feared the inherent potential for competition and conflict; they did not want their children to fight with outsiders and engender spiteful relations or become vulnerable to aggression and sorcery. Moreover, as their children did not attend school, they had no need for them to easily acquire skills of affiliating, negotiating, and competing with nonfamily agemates.

(C. P. Edwards, 1992, p. 305)

However, Edwards noted that the situation in Kenya is changing as the economy modernizes and literacy becomes an increasingly valued skill. Parents usually want their children to be educated, and education involves contact with peers. Indeed, in numerous kin-based societies, levels of interaction with peers who are not from the child’s family or clan increased dramatically when Westernized schooling was established (Rogoff, 2003; Tietjen, 2006), although in some cases, this contact has been restricted primarily to the school setting.

Cultures differ in terms of the total number of hours that children typically spend with peers. In many cultures, especially in unschooled, nonindustrial populations, boys tend to spend more time with peers than girls do, likely because they are less closely monitored and are allowed greater freedom to be away from home (Larson & Verma, 1999). For example, 6- to 12-year-old Indian boys were found to spend three times as much time with their peers outside their families than girls did (Saraswati & Dutta, 1988).

Among postindustrial schooled populations, European American, African American, and European adolescents have been found to spend much more time with peers, especially other-gender peers, than Asian adolescents do (Larson & Verma, 1999). In one study, for example, U.S. adolescents spent 18.4 hours per week with friends outside the classroom, whereas the time their Japanese and Taiwanese counterparts spent in out-of-school peer contact was, respectively, 12.4 and 8.8 hours per week (Fuligni & Stevenson, 1995). Moreover, East Asians tended to spend more of their time with peers studying than did U.S. youths, who were more inclined to engage in leisure activities with peers. Similar differences were evident in time spent dating, with Japanese and Taiwanese 11th-graders devoting roughly an hour a week to dating, compared with 4.7 hours per week for U.S. youths.

The cross-cultural differences in the amount of peer interaction adolescents engage in is likely due, at least in part, to cultural differences in values about what is important. A recent study of adolescents in 11 countries found that the greater the importance of traditional family values—defined as high feelings of family obligations, acceptance of children’s duty to be obedient, and an orientation toward the family instead of a focus on autonomy and individualism—the less peer acceptance was related to adolescents’ life satisfaction (Schwarz et al., 2012). Thus, in cultures with traditional family values, the peer group appears less important, and adolescents’ well-being is less related to how well liked they are by peers.

Adults’ expectations in regard to the nature of children’s interactions with peers also tend to differ across cultures. For example, there are cultural differences in the degree to which parents expect their children to develop such social skills as negotiating, taking the initiative, and standing up for their rights with peers. European American and European Australian mothers expect their children to develop such skills earlier than do Japanese mothers (Hess et al., 1980) and Lebanese Australian mothers (Goodnow et al., 1984). This is probably because the European American and European Australian mothers are influenced by their respective culture’s emphasis on personal autonomy and independence and believe that the aforementioned skills are important for success.

Correspondingly, Japanese mothers and Australian mothers of Lebanese heritage are likely to be similarly influenced by their respective cultures’ emphasis on the interdependence of family members; therefore, they may be more likely to accept or even encourage dependency in young children (F. A. Johnson, 1993; M. I. White & LeVine, 1986). Thus, differences in parents’ expectations regarding what social skills their children will develop and by what age likely influence what parents teach their children about social interactions with peers.

523

The extent to which friends’ use of drugs and alcohol may put adolescents at risk for use themselves seems to depend, in part, on the nature of the child–parent relationship. An adolescent with a substance-using close friend is at risk primarily if the adolescent’s parents are cold, detached, and uninclined to monitor and supervise the adolescent’s activities (Kiesner, Poulin, & Dishion, 2010; Mounts & Steinberg, 1995; Pilgrim et al., 1999). If the adolescent’s parents are authoritative in their parenting—monitoring their child’s behavior and setting firm limits, but also being warm and receptive to the adolescent’s viewpoint (see Chapter 12)—the adolescent is more likely to be protected against peer pressure to use drugs (Mounts, 2002).

Children’s Choice of Friends

What factors influence children’s choices of friends? As noted earlier, for young children, proximity is an obvious key factor. Preschoolers tend to become friends with peers who are nearby physically, as neighbors or playgroup members. (As Box 13.1 points out, young children’s access to peers can vary widely by culture.) Although proximity becomes less important with age, it continues to play a role in individuals’ choices of friends in adolescence (Clarke-McLean, 1996; Dishion, Andrews, & Crosby, 1995). This is partly because one form of proximity is involvement in similar activities at school (e.g., sports, academic activities, arts), which appears to promote the development of new friendships. In one study, when two adolescents participated in the same activity, they were on average 2.3 times more likely to be friends than were adolescents who did not participate in the same activity (Schaefer et al., 2011).

524

In most industrialized countries, similarity in age is also a major factor in friendship, with most children tending to make friends with age-mates (Aboud & Mendelson, 1996; Dishion et al., 1995). In part, this may be due to the fact that in most industrialized societies, children are segregated by age in school: in societies where children do not attend school or otherwise are not segregated by age, they are more likely to develop friendships with children of different ages.

Another powerful factor in friend selection is a child’s gender: girls tend to be friends with girls, and boys, with boys (Knecht et al., 2011; C. L. Martin et al., 2013; A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Cross-gender friendships, though not uncommon, tend to be more fragile (L. Lee, Howes, & Chamberlain, 2007; Maccoby, 2000; see Chapter 15). The preference for same-gender friends emerges in preschool and continues through childhood (Hartup, 1983). The liking of other-gender peers also increases over the course of childhood and into early adolescence (Poulin & Pedersen, 2007), with other-gender close friendships increasing in frequency from 8th grade to 11th grade (Arndorfer & Stormshak, 2008).

To a lesser degree, children tend to be friends with peers of their own racial/ethnic group, although this tendency varies across groups and contexts (Knecht et al., 2011). In general, efforts to establish friendships outside one’s own racial/ethnic group are less likely to be reciprocated than are efforts within the group (Vaquera & Kao, 2008); and when they are reciprocated, they often are not as long-lasting (L. Lee et al., 2007). In general, those youths with cross-racial/ethnic friendships tend to be leaders and relatively inclusive in their social relationships (Kawabata & Crick, 2008), as well as socially competent and high in self-esteem (N. Eisenberg, Valiente et al., 2009; Fletcher, Rollins, & Nickerson, 2004; Kawabata & Crick, 2011). For majority-group children, having cross-ethnic friendships has been associated with positive attitudes toward people in other groups in the future (Feddes, Noack, & Rutland, 2009). However, cross-race friendships can have costs: for example, middle-school African American and Asian American youths whose best friends are only of a different race from their own tend to be lower in emotional well-being than those with best friends only from the same racial group (McGill, Way, & Hughes, 2012).

Beyond these basic factors, a key determinant of liking and friendship is similarity of interests and behavior. By age 7, children tend to like peers who are similar to themselves in the cognitive maturity of their play (Rubin et al., 1994) and in the level of their aggressive behavior (Poulin et al., 1997). Between 4th grade and 8th grade, friends are more similar than nonfriends in their cooperativeness, antisocial behavior, acceptance by peers, and shyness (X. Chen, Cen et al., 2005; Haselager et al., 1998; A. J. Rose, Swenson, & Carlson, 2004). They are also more similar in their level of academic motivation and self-perceptions of competence (Altermatt & Pomerantz, 2003). Much the same pattern holds for adolescents (Dijkstra, Cillessen, & Borch, 2012; Gavin & Furman, 1996; Rubin et al., 2006), with the added dimensions that friends also tend to share similar levels of negative emotions such as distress and depression (Haselager et al., 1998; Hogue & Steinberg, 1995) and are similar in their tendency to attribute hostile intentions to others (Halligan & Philips, 2010).

525

Thus, birds of a feather do tend to flock together. The fact that friends tend to be similar on a number of dimensions underscores the difficulty of knowing whether friends actually affect one another’s behavior or whether children simply seek out peers who think, act, and feel as they do.

review:

Peers, especially friends, provide intimacy, support, and rich opportunities for the development of play and for the exchange of ideas. Children engage in more complex and cooperative play, and in more conflict, with friends than with nonfriends, and they tend to resolve conflicts with friends in more appropriate ways. With age, the dimensions of children’s friendships change somewhat. Whereas young children define friendship primarily on the basis of actual activities with their peers and on the rewards and costs involved, older children increasingly rely on their friends to provide a context for self-disclosure, intimacy, self-exploration, and problem solving. As was suggested by Piaget and Vygotsky, friends also provide opportunities for the development of important social and cognitive skills. However, friends can have negative effects on children if they engage in problematic behaviors such as aggression or substance abuse.

Children tend to become friends with peers who are similar in age, sex, race, and social behavior. This makes it especially difficult to distinguish between characteristics that children bring to friendships and the effects of friends on one another.