Prosocial Behavior

As noted earlier, moral behavior is as important for moral development as are moral thinking and moral emotions. The same is true for prosocial behavior; all children are capable of prosocial behaviors, but children differ in how often they engage in these behaviors and in their reasons for doing so. Consider the behavior of the following three preschool children:

Sara is drawing a picture and has a box of crayons. Erin is sitting across from her, and wants to draw. But Erin has only a single crayon and all the rest are in use by other children. She looks around for crayons of other colors. After a short time, Erin looks somewhat distressed. Sara notices that Erin is looking for crayons and is distressed, so she smiles and hands Erin a few of her own crayons, saying, “Here, do you want to use these?”

Marc is sitting at a table drawing with crayons when Manuel comes over and wants to draw. Manuel can’t find any crayons and shows signs of upset. Marc looks at Manuel and then returns to his own drawing. Finally, Manuel asks Marc, “Can I have some crayons?” At first Marc ignores Manuel. After Manuel asks for crayons again, Marc hands Manuel three crayons without any comment or display of emotion.

569

Sakina is drawing when Darren comes to the table, picks up a piece of paper, and looks around for crayons. When Darren can’t find any, he exhibits mild distress and then asks Sakina for some crayons. Sakina just ignores him. When Darren tries to take a crayon that Sakina is not using, Sakina angrily pushes him away.

(Eisenberg, unpublished laboratory observations)

Seeing that someone else is sad or in distress, Sara gladly shares without even being asked. Marc shares only if asked repeatedly. Sakina doesn’t share at all and does not seem to care if other children are upset. Do these differences in behavior forecast consistent differences in Sara’s, Marc’s, and Sakina’s positive moral behavior as they are growing up?

The answer is yes: there is some developmental consistency in children’s readiness to engage in prosocial behaviors, such as sharing, helping, and comforting (N. Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Knafo et al., 2008). In fact, children who, like Sara, share spontaneously with peers tend to be more concerned with others’ needs throughout childhood and adolescence and even in early adulthood. One longitudinal study found that, in comparison with their peers, for example, they were more likely to assist other people even when doing so involved a cost to themselves. As young adults, they reported that they felt responsible for the welfare of others and that they usually tried to suppress aggression toward others when angered. This view of themselves was supported by friends, who rated them as more sympathetic than study participants who engaged in less spontaneous prosocial behavior in preschool (N. Eisenberg et al., 2002; N. Eisenberg, Guthrie et al., 1999). In contrast, children like Sakina are unlikely to be concerned with others’ needs and feelings when they are older.

altruistic motives  helping others for reasons that initially include empathy or sympathy for others and, at later ages, the desire to act in ways consistent with one’s own conscience and moral principles

helping others for reasons that initially include empathy or sympathy for others and, at later ages, the desire to act in ways consistent with one’s own conscience and moral principles

Of course, not all prosocial behaviors are of equal worth. Sometimes children help or share to get something in return, to gain social acceptance from peers, or to avoid their anger (“I’ll share my doll if you’ll be my friend”). However, most parents and teachers want children to perform prosocial behaviors not for rewards or social approval but for altruistic motives. Altruistic motives initially include empathy or sympathy for others and, at later ages, the desire to act in ways consistent with one’s own conscience and moral principles (N. Eisenberg, 1986).

The Development of Prosocial Behavior

The origins of altruistic prosocial behavior are rooted in the capacity to feel empathy and sympathy. As discussed in Chapter 10, empathy is an emotional reaction to another’s emotional state or condition (e.g., sadness, poverty) that is highly similar to (or consistent with) the other person’s state or condition (N. Eisenberg, 1986; M. L. Hoffman, 2000). For example, if a child becomes sad upon observing another person’s sadness or pain, the child is experiencing empathy. To experience empathy, children must be able to identify the emotions of others (at least to some degree) and understand that another person is feeling an emotion or is in some kind of need.

570

Sympathy is a feeling of concern for another in reaction to the other’s emotional state or condition. Although sympathy often is an outcome of empathizing with another’s negative emotion or negative situation, what distinguishes sympathy from empathy is the element of concern: people who experience sympathy for another person are not merely feeling the same emotion as the other person.

An important factor contributing to empathy or sympathy is, obviously, the ability to take the perspective of others. Although early theorists such as Piaget believed that children are unable to do this until age 6 to 7 (Piaget & Inhelder, 1956/1977), it is now clear that children have some ability to understand others’ perspectives much earlier (Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2009). By 10 to 14 months of age, and occasionally between age 8 and 12 months, children sometimes become disturbed and upset when they view other people who are upset (Knafo et al., 2008; Roth-Hanania et al., 2011).

ANDY COX/GETTY IMAGES

Of course, it may be that infants are not really sympathizing with others’ distress; they may become upset merely because they do not differentiate clearly between another person’s emotional distress and their own (M. L. Hoffman, 2000). Indeed, young children sometimes seek comfort from a parent when they see someone else upset or are upset both for another person and for themselves (Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, & King, 1979).

By 18 to 25 months of age, toddlers in laboratory studies sometimes share a personal object with an adult whom they have viewed being harmed by another (for example, by having a piece of personal property taken away or destroyed). They also will sometimes comfort an adult who appears to be injured or distressed, or help an adult retrieve a dropped object or obtain food (Dunfield et al., 2011; Vaish et al., 2009). Such behaviors are especially likely to occur if the adult explicitly and emotionally communicates his or her need (C. A. Brownell, Svetlova, & Nichols, 2009), but they sometimes occur even when the adult does not express an emotional reaction (Vaish et al., 2009). (It should be noted that in studies like these, toddlers are particularly likely to help adults achieve a task or goal, like retrieving a dropped object [Warneken & Tomasello, 2006], but much less likely to share one of their own objects [Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010].) In displaying empathy, children in the second year of life also are more likely to try to comfort someone who is upset than to become upset themselves, indicating that they know who it is that is suffering. Consider the following example:

A neighbor’s baby boy cries. Jenny (18 months old) looked startled, her body stiffened. She approached and tried to give the baby cookies. She followed him around and began to whimper herself. She then tried to stroke his hair, but he pulled away. Later, Jenny approached her mother, led her to the baby, and tried to put mother’s hand on the baby’s head. He calmed down a little, but Jenny still looked worried. She continued to bring him toys and to pat his head and shoulders.

(Radke-Yarrow & Zahn-Waxler, 1984, p. 89)

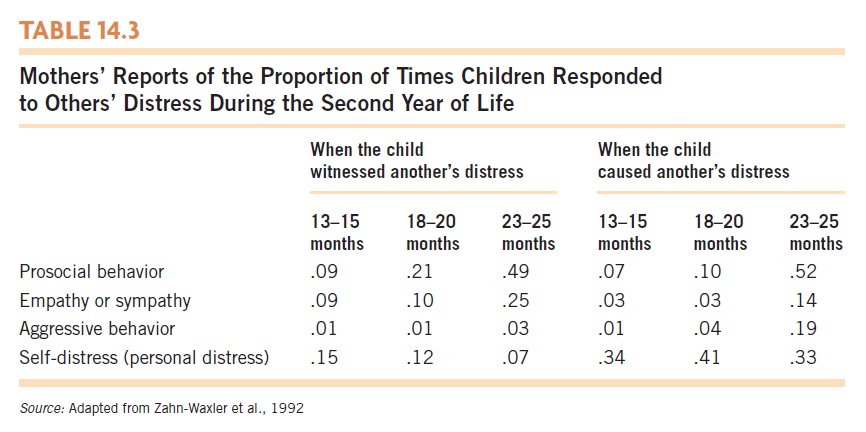

In the second and third years of life, the frequency and variety of young children’s prosocial behaviors increase. Children not only increasingly comfort others (see Table 14.3) and share objects but also assist adults with various tasks such as sweeping, carrying objects, or setting the table (Rheingold, 1982; Warneken, Chen, & Tomasello, 2006). Moreover, their prosocial behaviors at home often seem to be motivated by concern for others because they frequently show expressions of sympathy when they help or comfort others (Knafo et al., 2008; Radke-Yarrow & Zahn-Waxler, 1984). As shown in Table 14.3, 25% of 23- to 25-month-olds showed concern when they observed someone in distress that they had not caused themselves.

571

As should be clear from the table, however, young children do not regularly act in prosocial ways (S. Lamb & Zakhireh, 1997). Between the ages of 2 and 3, children most often ignore their siblings’ distress or need, or they simply watch without intervening. Occasionally, they even make the situation worse with teasing or aggression (Dunn, 1988; see “Aggressive behavior” in Table 14.3). In one study of children in a playgroup setting, for instance, 16- to 33-month-olds responded to peers’ distress only 22% of the time, usually by attempting to intervene on the peer’s behalf, comforting the peer, or bringing the peer’s distress to the attention of the caregiver (C. Howes & Farver, 1987). Consistent with our discussion in Chapter 13, these children were much more likely to help a friend than to help a child who was not a friend (N. Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006; Fujisawa, Kutsukake, & Hasegawa, 2008).

Children’s prosocial behaviors such as helping, sharing, and donating increase in frequency in the toddler years and from the preschool years through childhood (N. Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Knafo et al., 2008). However, prosocial behavior seems to stabilize or even decline in early to mid-adolescence and rebounds somewhat in late adolescence and early adulthood (Carlo et al., 2007; N. Eisenberg et al., 2005; Luengo Kanacri et al., 2013; Nantel-Vivier et al., 2009).

The Origins of Individual Differences in Prosocial Behavior

Although children’s prosocial behaviors change with age, consistent with the theme of individual differences, there is great variation among children of the same age in their propensity to help, share with, and comfort others. Recall the behaviors of Sara, Marc, and Sakina, the three children described earlier in this section. Why do children of the same ages differ so much in their prosocial behavior? To identify the origins of these individual differences, we must consider the themes of nature and nurture and sociocultural context.

Biological Factors

Many biologists and psychologists have proposed that humans are biologically predisposed to be prosocial (Hastings, Zahn-Waxler, & McShane, 2005). They believe that humans have evolved the capacity for empathy and altruism because these traits increase the likelihood of an individual’s genes being passed on to the next generation (M. L. Hoffman, 1981). According to this view, people who help others are more likely than less helpful people to be assisted when they themselves are in need and, thus, are more likely to survive and reproduce (Trivers, 1983). In addition, assisting those with whom they share genes increases the likelihood that those genes will be passed on to the next generation (E. O. Wilson, 1975). Evolutionary explanations for prosocial behavior, however, pertain to the human species as a whole and do not explain individual differences in empathy, sympathy, and prosocial behavior.

572

Nonetheless, genetic factors do contribute to individual differences in these characteristics (e.g., Waldman et al., 2011). In twin studies with adults, twins’ reports of their own empathy and prosocial behavior are considerably more similar for identical twins than for fraternal twins (Gregory et al., 2009; Knafo & Israel, 2010). In one of the few twin studies of children’s prosocial behavior, researchers observed young twins’ reactions to adults’ simulations of distress in the home and in the laboratory. They also had the twins’ mothers report on their everyday prosocial behavior. On the basis of heritability estimates derived from this study, it appears that the role that genetic factors play in the children’s prosocial concern for others and in their prosocial behavior increases with age (Knafo et al., 2008).

Recently, researchers have identified specific genes that might contribute to individual differences in prosocial tendencies (Knafo & Israel, 2010). For example, certain genes are associated with individual differences in oxytocin, a hormone that plays a role in a variety of social behaviors and emotion, including pair bonding and parenting, and has been associated with parental attachment, empathy, and prosocial behavior (N Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Knafo, under revision; R. Feldman, 2012; K. MacDonald & MacDonald, 2010; Striepens et al., 2011).

How else might genetic factors affect empathy, sympathy, and prosocial behavior? Most likely, their effects are related to differences in temperament. For instance, differences in children’s ability to regulate emotion are related to children’s empathy and sympathy. Children who tend to experience emotion without getting overwhelmed by it are especially likely to experience sympathy and to enact prosocial behavior (N. Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996; N. Eisenberg et al., 2007; Trommsdorff, Friedlmeier, & Mayer, 2007). Moreover, children who are not responsive to others’ emotions or are too inhibited to help others may be relatively unlikely to enact prosocial behaviors (Liew et al., 2011; S. K. Young, Fox, & Zahn-Waxler, 1999). Regulation is also related to children’s theory of mind (see page 267), and theory of mind predicts children’s prosocial behavior (Caputi et al., 2012). Thus, the effect of heredity on sympathy and prosocial behavior might be through individual differences in their social cognition. It seems, then, that genetic factors likely affect when and how children assist others through their effect on a number of different aspects of children’s functioning.

The Socialization of Prosocial Behavior

A number of environmental factors also contribute to sympathy and prosocial behavior (Knafo & Plomin, 2006a, 2006b; Volbrecht et al., 2007). The primary environmental influence on children’s development of prosocial behavior probably is their socialization in the family. Researchers have identified three ways in which parents socialize prosocial behavior in their children: (1) through their modeling and teaching prosocial behavior; (2) through their arranging opportunities for their children to engage in prosocial behavior; and (3) through their methods of disciplining their children and eliciting prosocial behavior from them. Parents also communicate and reinforce cultural beliefs about the value of prosocial behavior (see Box 14.1).

573

Box 14.1: a closer look

CULTURAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO CHILDREN’S PROSOCIAL AND ANTISOCIAL TENDENCIES

The amount of prosocial and antisocial behavior that children display can be influenced by the particular culture they are part of (Graves & Graves, 1983; Turnbull, 1972). For example, children from traditional communities and subcultures (e.g., Mexicans and Mexican Americans) are more likely to cooperate on laboratory tasks than are children from urban, Westernized groups (N. Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989; Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993). Similar patterns have been found in observations of children interacting at home and in their neighborhoods (Whiting & Edwards, 1988; Whiting & Whiting, 1975): children in traditional societies in Kenya, Mexico, and the Philippines helped, shared, and offered support to others in their families and communities more than did children in the United States, India, and Okinawa. In the more prosocial cultures, children often lived in extended families with many relatives. At a young age, they were assigned chores that were very important for the welfare of other family members, such as caring for younger children and tending herds. As a result of taking on these duties, children may have learned that they were responsible for others and that their helping behavior was expected and valued by adults.

However, there may be cultural differences in the people toward whom children’s caring behavior is directed. For example, in the research just discussed, Philippine children were more prosocial toward relatives than toward nonrelatives, whereas U.S. children were more prosocial toward nonrelatives than toward relatives (de Guzman, Carlo, & Edwards, 2008). Children in traditional cultures may be socialized to help people with whom they have close ties but may be relatively disinclined to help people with whom they don’t have a close connection.

The multicultural study cited above also revealed cultural differences in children’s aggression (Whiting & Whiting, 1975). Children’s tendencies to assault, berate, and scold others were related primarily to family structure and interactions among parents. Children with lower rates of assaulting and reprimanding tended to live in cultures in which fathers were closely involved with their wives and children, helped their wives with the care of infants, and were relatively unlikely to assault their wives. In such family circumstances, children may have learned nonaggressive modes of social interaction from their fathers and were relatively unlikely to have been exposed to aggressive adult models.

Even in various industrial societies today, there are differences in cultural values regarding prosocial and antisocial behavior. For instance, Mexican American youths are more prosocial if they espouse the traditional Mexican value of familism—a set of norms that promotes emotional and economic interdependence within an extended network of kin—rather than mainstream U.S. norms of individualism (Armenta et al., 2011). Along similar lines, the incidence of children’s sharing, helping, and comforting is higher in Taiwan and Japan than it is in the United States (Rao & Stewart, 1999; Stevenson, 1991). Again, in contrast to the U.S. valuing of self and competition, Chinese and Japanese cultures traditionally place great emphasis on teaching children to share and to be responsible for the needs of others in the group (the family, class, or community). In Japan, there also is an emphasis on creating a “community of learners” in the elementary school classroom—that is, teaching children to respond supportively to one another’s thoughts and feelings (M. Lewis, 1995). However, the traditional emphasis on prosocial behavior in many Asian cultures seems to be eroding (L. C. Lee & Zhan, 1991), perhaps due to increasing economic modernization and exposure to Western culture and values. This may explain why Asian children have not been found to be more prosocial than Western children in several relatively recent studies outside the classroom (Kärtner, Keller, & Chaudhary, 2010; Trommsdorff et al., 2007).

574

Modeling and the communication of values Just as they imitate many other behaviors, children tend to imitate other people’s helping and sharing behavior, including even that of unknown peers or adults (N. Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998). Children are especially likely to imitate the prosocial behavior of adults with whom they have a positive relationship (D. Hart & Fegley, 1995; Yarrow, Scott, & Zahn-Waxler, 1973). This may help explain the fact that parents and children tend to be similar in their levels of prosocial behavior and sympathy (Clary & Miller, 1986; N. Eisenberg et al., 1991; Stukas et al., 1999), although heredity may also contribute to the similarity between parent and child in sympathy and helpfulness.

In a particularly interesting study, individuals who had risked their lives to rescue Jews from the Nazis in Europe during World War II were interviewed many years later, along with “bystanders” from the same communities who had not been involved in rescue activities (Oliner & Oliner, 1988). As shown in Table 14.4, when recalling the values that they had learned from their parents and other influential adults, 44% of the rescuers mentioned generosity and caring for others, whereas only 21% of bystanders mentioned the same values. In addition, bystanders were almost twice as likely as rescuers to cite economic competence as a value learned from their parents.

Bystanders also reported that their parents emphasized ethical obligations to family, community, church, and country, but not to other groups of people. In contrast, rescuers were seven times more likely than bystanders to report that their parents taught them that values related to caring should be applied to everyone (28% of rescuers; 4% of bystanders):

“They taught me to respect all human beings.”

“He taught me to love my neighbor—to consider him my equal whatever his nationality or religion.”

(Oliner & Oliner, 1988, p. 165)

Thus, the values parents convey to their children may influence not only whether children are prosocial but also toward whom they are prosocial.

One effective way for parents to teach their children prosocial values and behaviors is to have discussions with them that appeal to their ability to sympathize. In laboratory studies, when elementary school children heard adults explicitly point out the positive consequences of prosocial actions for others (e.g., “Poor children…would be so happy and excited if they could buy food and toys”), they were relatively likely to donate money anonymously to help other people (Eisenberg-Berg & Geisheker, 1979; Perry, Bussey, & Freiberg, 1981). Children were less likely to donate anonymously if adults simply said that helping is “good” or “nice” and did not provide sympathy-arousing rationales for helping or sharing (Bryan & Walbek, 1970; N. Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998).

Opportunities for prosocial activities Providing children with opportunities to engage in helpful activities can increase their willingness to take on prosocial tasks at a later time (N. Eisenberg et al., 1987; Staub, 1979). In the home, opportunities to help others include household tasks that are performed on a routine basis and benefit others (Richman et al., 1988; Whiting & Whiting, 1975), although performance of household tasks may foster prosocial actions primarily toward family members (Grusec, Goodnow, & Cohen, 1996). For adolescents, voluntary community service such as working in homeless shelters or other community agencies also can be a way of gaining experience in helping others and deepening feelings of prosocial commitment (M. K. Johnson et al., 1998; Lawford et al., 2005; Pratt et al., 2003; Yates & Youniss, 1996).

575

Participation in prosocial activities may also provide opportunities for children and adolescents to take others’ perspectives, to increase their confidence that they are competent to assist others, and to experience emotional rewards for helping. Even mandatory school-based service activities have been associated with future prosocial values (D. Hart et al., 2007), as well as with increased voluntary service at a later date for those high school youths who were not initially inclined to engage in such activities (Metz & Youniss, 2003). It should be noted, however, that forcing older adolescents or young adults into service activities can sometimes backfire and undermine their motivation to help (Stukas, Snyder, & Clary, 1999).

Discipline and parenting style High levels of prosocial behavior and sympathy in children tend to be associated with constructive and supportive parenting, including authoritative parenting (Day & Padilla-Walker, 2009; Knafo & Plomin, 2006a; Michalik et al., 2007). When parents are involved with and close to their children, children are higher in sympathy and regulation, which in turn predicts higher levels of prosocial behavior (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011). Parental support of, and attachment to, the child have been found to be especially predictive of prosocial behavior for youths who are low in fearfulness (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2010). It is important to note, however, that not only might supportive, authoritative parenting promote sympathy and prosocial behavior, but prosocial, sympathetic children might also elicit more support from their parents (Miklikowska, Duriez, & Soenens 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2012). In contrast, a parenting style that involves physical punishment, threats, and an authoritarian approach (see Chapter 12) tends to be associated with a lack of sympathy and prosocial behavior in children (Asbury et al., 2003; Hastings et al., 2000; Krevans & Gibbs, 1996; Laible et al., 2008).

The way in which parents attempt to directly elicit prosocial behavior from their children is also important. If children are regularly punished for failing to engage in prosocial behavior, they may start to believe that the reason for helping others is primarily to avoid punishment (Dix & Grusec, 1983; M. L. Hoffman, 1983). Similarly, if children are given material rewards for prosocial behaviors, they may come to believe that they helped solely for the rewards and, thus, may be less motivated to help when no rewards are offered (Fabes et al., 1989; Warneken & Tomasello, 2008).

What does seem particularly likely to foster children’s voluntary prosocial behavior is discipline that involves reasoning (Carlo, Mestre et al., 2010). This is especially true when the reasoning points out the consequences of the child’s behavior for others (Krevans & Gibbs, 1996), encourages perspective taking (B. M. Farrant et al., 2012), and is used by parents who generally are warm and supportive (M. L. Hoffman, 1963). Such reasoning also encourages sympathy with others and provides guidelines children can refer to in future situations (C. S. Henry, Sager, & Plunkett, 1996; M. L. Hoffman, 1983). Maternal use of reasoning (e.g., “Can’t you see that Tim is hurt?”) seems to increase prosocial behavior even for 1- to 2-year-olds, as long as mothers state their reasoning in an emotional tone of voice (Zahn-Waxler et al., 1979). Emotion in the mother’s voice likely catches her toddler’s attention and communicates that she is very serious about what she is saying.

576

The combination of parental warmth and certain parenting practices—not parental warmth by itself—seems to be especially effective for fostering prosocial tendencies in children. Thus, children tend to be more prosocial when their parents are not only warm and supportive but also model prosocial behavior, include reasoning and references to moral values and responsibilities in their discipline, and expose their children to prosocial models and activities (i.e., use authoritative parenting; Hastings et al., 2007; Janssens & Dekovic, 1997; Yarrow et al., 1973).

Because most of the research on the socialization of prosocial responding is correlational in design, it does not allow firm conclusions about cause-and-effect relations. However, some school interventions have been effective at promoting prosocial behavior in children, so environmental factors must contribute to its development (see Box 14.2). The research underlying such interventions indicates that experience in helping and cooperating with others, exposure to prosocial values and behaviors, and adults’ use of reasoning in discipline jointly contribute to the development of prosocial behavior.

Box 14.2: applications

SCHOOL-BASED INTERVENTIONS FOR PROMOTING PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR

Knowledge about the socialization of helping and sharing behavior has been used to design school interventions aimed at fostering such behavior. Perhaps the most ambitious of these interventions was the Child Development Project in the East Bay area of San Francisco (Battistich et al., 1991; Battistich et al., 1997). This longitudinal intervention, which followed children across elementary school, trained teachers in providing opportunities for children to develop a prosocial orientation toward their classmates and the community. The training focused on getting children to do the following:

- Collaborate with others to achieve common academic and social goals

- Develop and practice important social competencies such as understanding of others’ thoughts and feelings

- Provide meaningful help to others and receive help when it was needed

- Discuss and reflect upon the degree to which their own and others’ behavior reflects fairness, concern and respect for others, and social responsibility

- Participate in decision making about classroom norms, rules, and activities and take on responsibility for appropriate aspects of classroom life

The program has led to increases in spontaneous prosocial behavior, prosocial moral reasoning, and conflict-resolution skills (D. Solomon, Battistich, & Watson, 1993; D. Solomon et al., 1988). However, some programs involving a shorter period (a year or a limited number of lessons) and a focus on empathy training, anger management, impulse control, and problem solving have produced more limited evidence of improvements in empathy or prosocial behavior—that is, improvements on some measures such as self- or teacher-reports but not on peers’ reports or observed behavior, or at one school but not another (Cooke et al., 2007; S. D. McMahon & Washburn, 2003). Programs are probably most effective when sustained and well integrated into numerous aspects of school programs.

The concept of the school as a caring community becomes a central part of similar interventions. The caring school community is one in which teachers and students (1) care about and support one another; (2) share common values, norms, goals, and a sense of belonging; and (3) participate in and influence group decisions. Programs designed to promote caring school communities included many of the components of the original Child Development Project. Findings with diverse samples of children suggest that enhancing a sense of school community not only promotes children’s concern for others, fostering prosocial behavior, conflict-resolution skills, and ethical attitudes and values; it also increases academic motivation and liking of school and is associated with fewer problem behaviors and less use of drugs (Battistich et al., 1997; Battistich et al., 2000; Battistich, Schaps, & Wilson, 2004; D. Solomon et al., 2000).

577

review:

Prosocial behaviors emerge by the second year of life and increase in frequency during the toddler years. At least some types of prosocial behavior continue to increase in frequency and sensitivity in the preschool years and elementary school years. Early individual differences in prosocial behavior predict differences among children in these types of behaviors years later.

Prosocial behavior may increase with age in childhood partly because of children’s developing abilities to sympathize and take others’ perspectives. Differences among children in their empathy, sympathy, distress reactions to others’ distress, and perspective taking also contribute to individual differences in children’s prosocial behavior. Furthermore, biological factors, which may contribute to differences among children in temperament, likely affect how empathic and prosocial children become.

The development of prosocial behavior also is related to children’s upbringing. In general, a positive relationship between parents and children is linked to prosocial moral development, especially when supportive parents use effective parenting practices. Authoritative, positive discipline—including the use of reasoning by parents and teachers and exposure to prosocial models, values, and activities—is associated with the development of sympathy and prosocial behavior. Cultures differ in the degree to which they value and teach prosocial behavior, and these differences are reflected in how much children help, share with, and are concerned about other people and perhaps whom they assist.

Intervention programs in schools designed to foster prosocial behavior sometimes have been found to increase children’s prosocial behavior and prosocial moral reasoning; whether a given intervention is effective probably depends on its content, length, and the degree to which it is effectively administered. Such findings convincingly demonstrate that social factors (as well as heredity) contribute to the development of prosocial tendencies.