Milestones in Gender Development

Developmental psychologists have identified general patterns that tend to occur over the course of children’s gender development. As reviewed next, gender-related changes are evident in children’s physical, cognitive, and social development. Recall that these changes begin during prenatal development, when sexual differentiation occurs.

608

Infancy and Toddlerhood

During their first year, infants’ perceptual abilities allow them to figure out that there are two groups of people in the world: females and males. As we saw in Chapter 5, much research indicates that infants can detect complex regularities in perceptual information. Clothing, hairstyle, height, body shape, motion patterns, vocal pitch, and activities all tend to vary with gender, and these differences provide infants with gender cues. For example, habituation studies of infant perception and categorization indicate that by about 6 to 9 months of age, infants can distinguish males and females, usually on the basis of hairstyle (Intons-Peterson, 1988). Infants can also distinguish male and female voices and make intermodal matches on the basis of gender (C. L. Martin et al., 2002). For instance, they expect a female voice to go with a female face rather than with a male face. Although we cannot conclude that infants understand anything about what it means to be female or male, it does appear that older infants recognize the physical difference between females and males by using multiple perceptual cues.

Shortly after entering toddlerhood, children begin exhibiting distinct patterns of gender development. By the latter half of their second year, children have begun to form gender-related expectations about the kinds of objects and activities typically associated with males and females. For example, 18-month-olds looked longer at a doll than at a toy car after viewing a series of female faces, and looked longer at a toy car than at a doll after habituating to male faces (Serbin et al., 2001). Another study with 24-month-olds found that counter-stereotypical matches of gender and action (e.g., a man putting on lipstick) led to longer looking times; it appeared that the children were surprised by the action’s gender inconsistency (Poulin-Dubois et al., 2002).

The clearest evidence that children have acquired the concept of gender occurs around 2½ years of age, when they begin to label other people’s genders. For example, researchers might assess this ability by asking children to put pictures of children into “boys” and “girls” piles. Toddlers can also make simple gender matches, such as choosing a toy train over a doll when asked to point to the “boy’s toy” (A. Campbell, Shirley, & Caygill, 2002). Children typically begin to show understanding of their own gender identity within a few months after labeling other people’s gender. By age 3, most children use gender terms such as “boy” and “girl” in their speech and correctly refer to themselves as a boy or girl (Fenson et al., 1994).

Preschool Years

During the preschool years, children quickly learn gender stereotypes—the activities, traits, and roles associated with each gender. By around 3 years of age, most children begin to attribute certain toys and play activities to each gender. By around 5 years of age, they usually stereotype affiliative characteristics to females and assertive characteristics to males (Best & Thomas, 2004; Biernat, 1981; Liben & Bigler, 2002; Serbin, Powlishta, & Gulko, 1993). During this period, children usually lack gender constancy: they do not understand that gender remains stable across time and is consistent across situations. For example, a preschooler might think that a girl becomes a boy if she cuts her hair, or that a boy becomes a girl if he wears a dress.

609

Gender-Typed Behavior

Many children begin to demonstrate preferences for some gender-typed toys by around 2 years of age. These preferences become stronger for most children during the preschool years (Cherney & London, 2006; Pomerleau et al., 1990; Rheingold & Cook, 1975). Indeed, during childhood, one of the largest average gender differences is in toy and play preferences. Girls are more likely than boys to favor dolls, toy cooking sets, and dress-up materials. Girls are also more likely to invoke domestic themes (such as playing house) in their fantasy play. In contrast, boys are more likely than girls to prefer cars, trucks, building toys, and sports equipment. Boys also are more likely than girls to engage in rough-and-tumble play and to enact action-and-adventure themes (such as playing super-heroes) in their fantasy play.

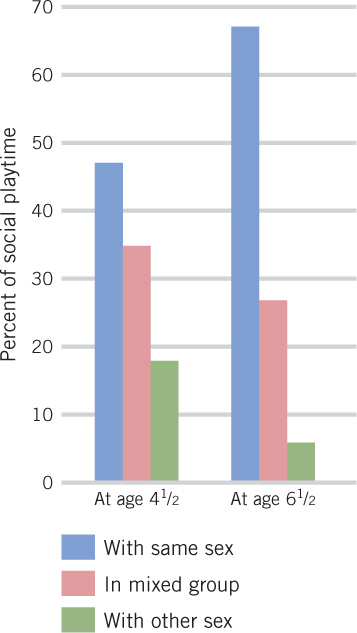

The preschool period is also when gender segregation emerges, as children start to prefer playing with same-gender peers and to avoid other-gender peers (Leaper, 1994; Maccoby, 1998). Gender segregation increases steadily between around 3 and 6 years of age, then remains stable throughout childhood (Figure 15.2). Children’s preference for same-gender peers is seen across different cultures; however, there are some cultural variations in the degree that children play exclusively with their own gender (Whiting & Edwards, 1988).

Gender-segregated peer groups are a laboratory for children to learn what it means to be a girl or a boy. Peers are both role models and enforcers of gender-typed behavior. Martin and Fabes (2001) identified what they termed a “social dosage effect” of belonging to same-gender peer groups during early childhood. The amount of time that preschool or kindergarten children spent with same-gender peers predicted subsequent changes in gender-typed behavior over 6 months. For example, boys who spent more time playing with same-gender peers showed increases over time in aggression, rough-and-tumble play, activity level, and gender-typed play. Girls who spent more time playing with same-gender peers showed increases in gender-typed play and decreases in aggression and activity level.

gender segregation  children’s tendency to associate with same-gender peers and to avoid other-gender peers

children’s tendency to associate with same-gender peers and to avoid other-gender peers

The reasons for children’s same-gender peer preferences seem to involve a combination of temperamental, cognitive, and social forces (Maccoby, 1998). Their relative influences change over time. At first, children appear to prefer same-gender peers because they have more compatible behavioral styles and interests. For instance, girls may avoid boys because boys tend to be rough and unresponsive to girls’ attempts to influence them, and boys may prefer the company of other boys because they share similar activity levels. Around the time that children begin to exhibit a same-gender peer preference, they also are establishing a gender identity and therefore are further drawn to peers who belong to the same ingroup.

610

As they get older, peer pressures may additionally motivate children to favor same-gender peers. Thus, behavioral compatibility may become a less important factor with age. For example, physically active girls may frequently play with boys during early childhood; however, as these girls get older, they tend to affiliate more with girls—even though their activity preferences may be more compatible with those of boys than with those of girls (Pellegrini et al., 2007). Therefore, ingroup identity and conformity pressures may supersede behavioral compatibility as reasons for gender segregation as children get older.

Middle Childhood

By around 7 years of age, children have attained gender constancy, and their ideas about gender are more consolidated. At this point, children often show a bit more flexibility in their gender stereotypes and attitudes than they did in their younger years (P. A. Katz & Ksansnak, 1994; Liben & Bigler, 2002; Serbin, Powlishta, & Gulko, 1993). For example, they may recognize that some boys don’t like playing baseball and that some girls don’t wear dresses. However, most children continue to be highly gender-stereotyped in their views.

Around 9 or 10 years of age, children start to show an even clearer understanding that gender is a social category. They typically recognize that gender roles are social conventions as opposed to biological outcomes (D. B. Carter & Patterson, 1982; Stoddart & Turiel, 1985). As children come to appreciate the social basis of gender roles, they may recognize that some girls and boys may not want to do things that are typical for their gender. Some children may even argue that, in such cases, other girls and boys should be allowed to follow their personal preferences. For instance, Damon (1977) found that children would say that a boy who liked to play with dolls should be allowed to do so. However, children also recognized that the boy would probably be teased and that they themselves would not want to play with him. That is, children understood the notion of individual variations in gender typing, but they were also aware that violating gender role norms would have social costs.

Another development in children’s thinking is realizing that gender discrimination is unfair and noticing when it occurs (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2005; Killen, 2007). Killen and Stangor (2001) demonstrated this when they told children stories about a child who was excluded from a group because of the child’s gender. Examples included a boy who was kept out of a ballet club and a girl who was kept out of a baseball-cards club. Eight- and 10-year-olds consistently judged it unfair for a child to be excluded from a group solely because of gender. Despite their capacity to see this as wrong, children commonly exclude other children from activities based on their gender (Killen, 2007; Maccoby, 1998).

Brown and Bigler (2005) identified various factors that affect whether children recognize gender discrimination. First among them are cognitive prerequisites, such as having an understanding of cultural stereotypes, being able to make social comparisons, and having a moral understanding of fairness and equity. These abilities are typically reached by middle childhood. People’s awareness of sexism can also be influenced by individual factors such as their self-concepts or beliefs. For example, girls with gender-egalitarian beliefs were more likely to recognize sexism (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2004; Leaper & Brown, 2008). Finally, the specific situation can affect children’s likelihood of noticing discrimination. For instance, children are more likely to notice discrimination directed toward someone else than toward themselves. Also, they are more apt to recognize gender discrimination in someone known to be prejudiced (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2005).

611

Gender-Typed Behavior

In middle childhood, many boys’ and girls’ peer groups establish somewhat different gender-role norms for behavior (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). For this reason, some researchers have suggested that each gender usually constructs its own “culture” during childhood (Maccoby, 1998; Maltz & Borker, 1982; Thorne & Luria, 1986). In line with their tendency to value self-assertion over affiliation, boys’ peer groups are more likely to reflect norms of dominance, self-reliance, and hiding vulnerability. Conversely, in line with their greater tendency to value affiliative goals (or a balance of affiliative and assertive goals), girls’ peer groups are more likely to reflect norms of intimacy, collaboration, and emotional sharing (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006).

As we have noted, when children violate gender-role norms, their peers often react negatively (Fagot, 1977), including mercilessly teasing someone who has crossed gender “borders.” The following description of an event in an American elementary school clearly illustrates the degree to which children enforce gender segregation on their own:

In the lunchroom, when the two second-grade tables were filling, a high-status [popular] boy walked by the inside table, which had a scattering of both boys and girls, and said loudly, “Oooo, too many girls,” as he headed for a seat at the far table. The boys at the inside table picked up their trays and moved, and no other boys sat at the inside table, which the pronouncement had effectively made taboo.

(Thorne, 1986, p. 171)

Although most children typically favor same-gender peers, in certain contexts friendly cross-gender contacts regularly occur in North American and other Western cultures (Sroufe et al., 1993; Strough & Covatto, 2002; Thorne, 1993; Thorne & Luria, 1986). At home and in the neighborhood, the choice of play companions is frequently limited. As a result, girls and boys often play cooperatively with one another. In more public settings, the implicit convention is that girls and boys can be friendly if they can attribute the reason for their cross-gender contact to an external cause. For example, this might occur when a teacher assigns them to work together on a class project or when they are waiting in line together at the cafeteria. However, beyond such exceptions, the risk of peer rejection is high when children violate the convention to avoid cross-gender contact (Sroufe et al., 1993).

Overall, gender typing during childhood tends to be more rigid among boys than among girls (Leaper, 1994; Levant, 2005). As noted earlier, boys are more likely to endorse gender stereotypes than are girls, who tend to endorse gender-egalitarian attitudes (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2004). In addition, girls are less gender-typed in their behavior. Girls are more likely than boys to play with cross-gender-typed toys, for example. Also, girls tend to be more flexible in coordinating interpersonal goals. For instance, girls commonly coordinate both affiliative and assertive goals in their social interactions (Leaper, 1991; Leaper & Smith, 2004). That is, girls are more likely than boys to use collaborative communication that affirms both the self and the other (e.g., proposals for joint activity), whereas boys are more likely than girls to use power-assertive communication that primarily affirms the self (e.g., giving commands). Girls, however, also frequently pursue play activities traditionally associated with boys, as in sports such as soccer and basketball. In contrast, it is relatively rare to see boys engage in activities traditionally associated with girls, such as playing house.

612

Adolescence

gender-role intensification  heightened concerns with adhering to traditional gender roles that may occur during adolescence

heightened concerns with adhering to traditional gender roles that may occur during adolescence

For some girls and boys, adolescence can be a period of either increased gender-role intensification (Galambos, Almeida, & Petersen, 1990; J. P. Hill & Lynch, 1983) or increased gender-role flexibility (D. B. Carter & Patterson, 1982; P. A. Katz & Ksansnak, 1994). Gender-role intensification refers to heightened concerns with adhering to traditional gender roles. Factors associated with adolescence, such as concerns with romantic attractiveness or conventional beliefs regarding adult gender roles, may intensify some youths’ adherence to traditional gender roles. Alternatively, advances in cognitive development can lead to greater gender-role flexibility, whereby adolescents may reject traditional gender roles as social conventions and pursue a flexible range of attitudes and interests (see Box 15.4). As in childhood, greater gender-role flexibility during adolescence is more likely among girls than among boys. For example, many girls and young women in the United States and other countries participate in sports and pursue careers in business (traditionally male-dominated domains), whereas relatively few boys and young men show similar levels of interest in child care or homemaking.

gender-role flexibility  recognition of gender roles as social conventions and adoption of more flexible attitudes and interests

recognition of gender roles as social conventions and adoption of more flexible attitudes and interests

During late childhood and adolescence, as children increasingly develop an understanding that norms about gender roles are social conventions, they may nevertheless endorse the conventions. Thus, adolescents may believe it is legitimate to exclude cross-gender peers from their peer group, because they feel that to include them would be violating the group’s gender norms and social conventions (Killen, 2007). Researchers also find that girls tend to perceive more gender discrimination during the course of adolescence (Leaper & Brown, 2008). This trend is likely due to a combination of experiencing increased sexism (American Association of University Women, 2011; S. E. Goldstein et al., 2007; McMaster et al., 2002) and having an increased awareness of sexism (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2005; Leaper & Brown, 2008).

Gender-Typed Behavior

During early adolescence, peer contacts are primarily members of the same gender. However, cross-gender interactions and friendships usually become more common during adolescence (Poulin & Pedersen, 2007). As described in Chapter 13, these interactions can open the way to romantic relationships. Adolescence is also a period of increased intimacy in same-gender friendships. For many girls and boys, increased emotional closeness is often attained through sharing personal feelings and thoughts, although there appears to be more variability among boys in the ways they experience and express closeness in friendships (Camarena, Sarigiani, & Petersen, 1990). While some boys attain intimacy through shared disclosures with same-gender friends, other boys tend to avoid self-disclosure with same-gender friends because they wish to appear strong. Instead, they usually attain a feeling of emotional closeness with friends through shared activities, such as playing sports. At the same time, many boys who avoid expressing feelings with male friends will do so with their female friends or girlfriends (Youniss & Smollar, 1985).

613

Box 15.4: a closer look

GENDER FLEXIBILITY AND ASYMMETRY

Gender typing is more rigid for boys than for girls at all ages. Most boys engage almost exclusively in activities considered to be either masculine or gender-neutral, while many girls engage in activities stereotyped for boys (Bussey & Bandura, 1992; Fagot & Leinbach, 1993). This difference in gender flexibility seems to stem in large part from males’ avoidance of feminine-stereotyped activities in addition to their preference for masculine-stereotyped ones (Bussey & Bandura, 1992; C. L. Martin, Eisenbud, & Rose, 1995; Powlishta, Serbin, & Moller, 1993). By age 5, boys are more likely than girls to say that they dislike cross-gender-typed toys (Bussey & Bandura, 1992; Eisenberg-Berg, Murray, & Hite, 1982). The rigid preference for gender-typed objects and activities—along with the bias against cross-gender-typed objects and activities—declines during the school years; however, boys remain relatively stricter about gender typing than do girls (Serbin et al., 1993).

One reason for boys’ greater avoidance of feminine-stereotyped activities is an asymmetry in the extent to which most people find it acceptable for boys and girls to engage in activities deemed more appropriate for the other gender. Generally, parents, peers, and teachers respond more negatively to boys who do “girl things” than vice versa. A child of one of this book’s authors, for instance, attended preschool with a girl who spent most of her time in the block-building area and a boy who, almost every day, selected a pink tutu from the dress-up corner to wear over his clothes. The teachers, parents, and other adults who observed these two children were concerned about the boy’s behavior but not the girl’s behavior.

Suppose you had a daughter who liked to play with toy soldiers and a son who liked to play with a baby doll. Would you find one of these more acceptable than the other? Also, imagine you heard another child call your daughter a “tomboy” or you heard someone refer to your son as a “sissy.” Would your reactions be different? According to one study, adults tended to find a “tomboy” girl considerably more acceptable than a “sissy” boy (C. L. Martin, 1990).

Many fathers play an active role in nstilling male behaviors in their sons and in enforcing the avoidance of feminine behaviors (Jacklin, DiPietro, & Maccoby, 1984; Leve & Fagot, 1997; P. J. Turner & Gervai, 1995). They generally react negatively to their sons for doing anything “feminine,” such as crying or playing with dolls. Consider the difference in what this mother and father say to their son when he hurts himself:

Mother: “Come here, honey. I’ll kiss it better.”

Father: “Oh, toughen up. Quit your bellyaching.”

(Gable, Belsky, & Crnic, 1993, p. 32)

Why are many parents and other adults more upset when boys engage in cross-gender-typed behaviors than they are when girls do? According to social identity theory and social role theory, the asymmetry is tied to men’s higher status in society and the emphasis on dominance in the traditional male gender role. When boys show interest in feminine-stereotyped characteristics, people with traditional attitudes view the boys’ behavior as a loss in status. Conversely, when girls exhibit certain masculine-stereotyped qualities, those qualities are more likely to be seen as conferring status (Leaper, 1994). For example, a boy who wants to babysit may be ridiculed for being “soft,” but a girl who wants to play ice hockey may be praised for being “strong.”

In many cultures, caring for children is viewed as a strength. Among the Aka hunter-gatherers in Africa, for example, child care is not viewed as a solely feminine activity and is in fact shared by men and women (Hewlett, 1991). A similar pattern is emerging among dual-career heterosexual parents in North America and other Western cultures. Many fathers are more involved in child care these days than was true in previous generations (S. N. Davis & Greenstein, 2004). However, in most heterosexual families, mothers are usually responsible for most child care and housework (Sayer, 2005).

614

Self-disclosure and supportive listening are generally associated with relationship satisfaction and emotional adjustment (Leaper & Anderson, 1997; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). However, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. This occurs when friends dwell too long on upsetting events by talking to one another about them over and over. As discussed in Chapter 10, this process of co-rumination is more common among girls than among boys (A. J. Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007). Although it may foster feelings of closeness between friends, co-rumination appears to increase depression and anxiety in girls (but not in boys).

review:

By about 6 to 9 months of age, infants can distinguish between females and males on the basis of perceptual cues. Between ages 2 and 3 years, children identify their own gender, after which they begin acquiring stereotypes regarding culturally prescribed activities and traits associated with each gender. They also start to demonstrate gender-typed play preferences. During the preschool period, children begin a process of self-initiated gender segregation that lasts through childhood and is strongly enforced by peers.

Around 7 years of age, children have acquired gender constancy and consolidated their understanding of gender. During middle childhood, children are capable of recognizing gender discrimination. Adolescence is a period that can involve increased gender-role rigidity or flexibility. It is also a time when girls are more likely to experience gender discrimination (sexism). Throughout childhood and adolescence, gender-role rigidity tends to be more common among boys, and gender-role flexibility tends to be more common among girls. Friendship intimacy also increases during adolescence, although intimacy is more common among girls than among boys.