Enduring Themes in Child Development

The modern study of child development begins with a set of fundamental questions. Everything else—theories, concepts, research methods, data, and so on—is part of the effort to answer these questions. Although experts in the field might choose different particular questions as the most important, there is widespread agreement that the seven questions in Table 1.1 are among the most important. These questions form a set of themes that we will highlight throughout the book as we examine specific aspects of child development. In this section, we introduce and briefly discuss each question and the theme that corresponds to it.

Nature and Nurture: How Do Nature and Nurture Together Shape Development?

Nature and Nurture: How Do Nature and Nurture Together Shape Development?

nature  our biological endowment; the genes we receive from our parents

our biological endowment; the genes we receive from our parents

The most basic question about child development is how nature and nurture interact to shape the developmental process. Nature refers to our biological endowment, in particular, the genes we receive from our parents. This genetic inheritance influences every aspect of our make-up, from broad characteristics such as physical appearance, personality, intellect, and mental health to specific preferences, such as political attitudes and propensity for thrill-seeking (Plomin, 2004; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Nurture refers to the wide range of environments, both physical and social, that influence our development, including the womb in which we spend the prenatal period, the homes in which we grow up, the schools that we attend, the broader communities in which we live, and the many people with whom we interact.

nurture  the environments, both physical and social, that influence our development

the environments, both physical and social, that influence our development

11

Popular depictions often present the nature–nurture question as an either/or proposition: “What determines how a person develops, heredity or environment?” However, this either/or phrasing is deeply misleading. All human characteristics—our intellect, our personality, our physical appearance, our emotions—are created through the joint workings of nature and nurture, that is, through the constant interaction of our genes and our environment. Accordingly, rather than asking whether nature or nurture is more important, developmentalists ask how nature and nurture work together to shape development.

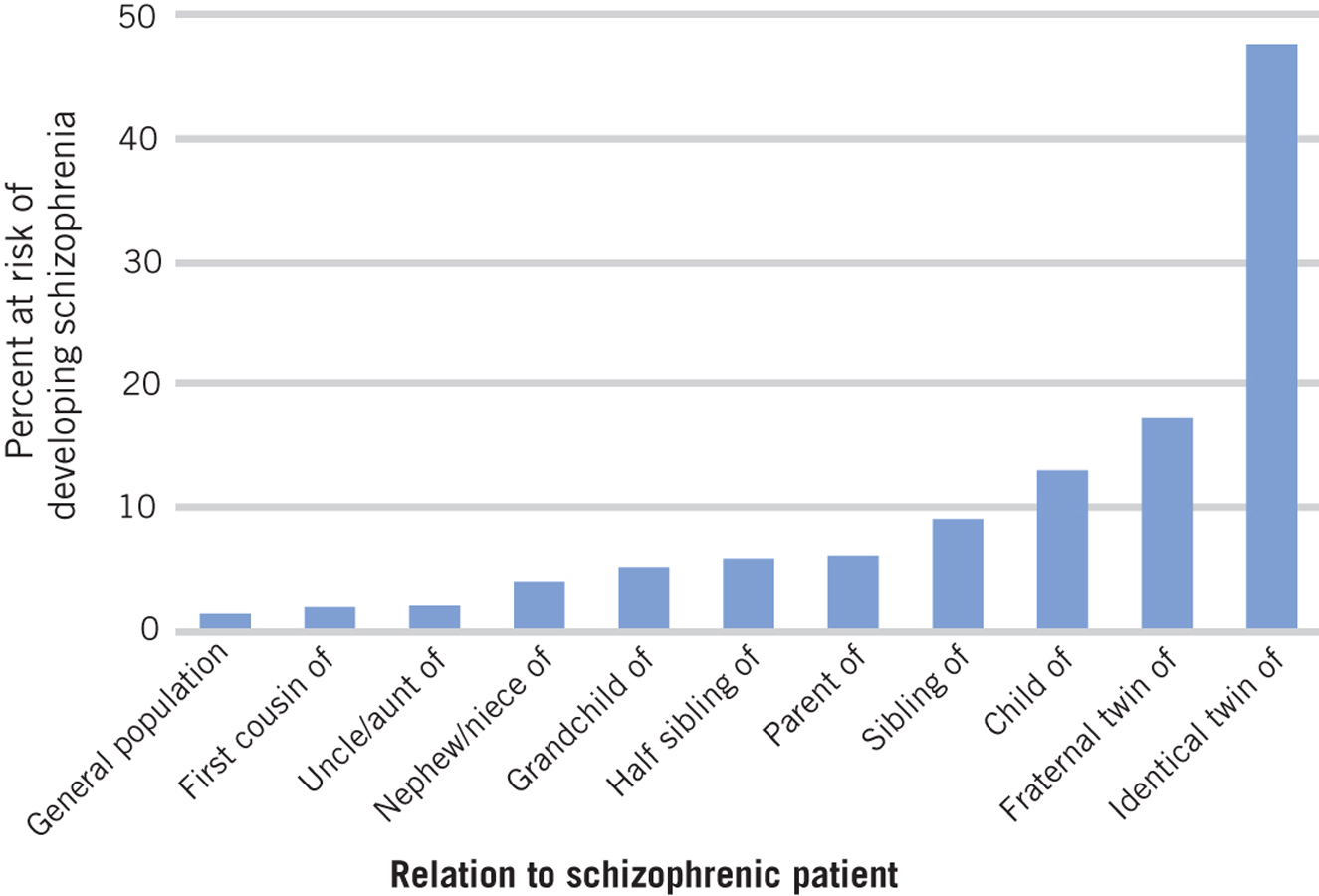

That this is the right question to ask is vividly illustrated by findings on the development of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness, often characterized by hallucinations, delusions, confusion, and irrational behavior. There is obviously a genetic component to this disease. Children who have a schizophrenic parent have a much higher probability than other children of developing the illness later in life, even when they are adopted as infants and therefore are not exposed to their parents’ schizophrenic behavior (Kety et al., 1994). Among identical twins—that is, twins whose genes are identical—if one twin has schizophrenia, the other has a roughly 50% chance of also having schizophrenia, as opposed to the roughly 1% probability for the general population (Gottesman, 1991; Cardno & Gottesman, 2000; see Figure 1.1). At the same time, the environment is also clearly influential, since roughly 50% of children who have an identical twin with schizophrenia do not become schizophrenic themselves, and children who grow up in troubled homes are more likely to become schizophrenic than are children raised in a normal household. Most important, however, is the interaction of genes and environment. A study of adopted children, some of whose biological parents were schizophrenic, indicated that the only children who had any substantial likelihood of becoming schizophrenic were those who had a schizophrenic parent and who also were adopted into a troubled family (Tienari, Wahlberg, & Wynne, 2006).

genome  each person’s complete set of hereditary information

each person’s complete set of hereditary information

A remarkable recent series of studies has revealed some of the biological mechanisms through which nature and nurture interact. These studies show that just as the genome—each person’s complete set of hereditary information—influences behaviors and experiences, behaviors and experiences influence the genome (Cole, 2009; Meaney, 2010). This might seem impossible, given the well-known fact that each person’s DNA is constant throughout life. However, the genome includes not only DNA but also proteins that regulate gene expression by turning gene activity on and off. These proteins change in response to experience and, without structurally altering DNA, can result in enduring changes in cognition, emotion, and behavior. This discovery has given rise to a new field called epigenetics, the study of stable changes in gene expression that are mediated by the environment. Stated simply, epigenetics examines how experience gets under the skin.

12

epigenetics  the study of stable changes in gene expression that are mediated by the environment

the study of stable changes in gene expression that are mediated by the environment

Evidence for the enduring epigenetic impact of early experiences and behaviors comes from research on methylation, a biochemical process that reduces expression of a variety of genes and that is involved in regulating reactions to stress (Champagne & Curley, 2009; Meaney, 2001). One recent study showed that the amount of stress that mothers reported experiencing during their children’s infancy was related to the amount of methylation in the children’s genomes 15 years later (Essex et al., 2013). Other studies showed increased methylation in the cord-blood DNA of newborns of depressed mothers (Oberlander et al., 2008) and in adults who were abused as children (McGowan et al., 2009), leading researchers to speculate that such children are at heightened risk for depression as adults (Rutten & Mill, 2009).

methylation  A biochemical process that influences behavior by suppressing gene activity and expression

A biochemical process that influences behavior by suppressing gene activity and expression

As these examples illustrate, developmental outcomes emerge from the constant bidirectional interaction of nature and nurture. To say that one is more important than the other, or even that the two are equally important, drastically oversimplifies the developmental process.

The Active Child: How Do Children Shape Their Own Development?

The Active Child: How Do Children Shape Their Own Development?

With all the attention that is paid to heredity and environment, many people overlook the ways in which children’s own actions contribute to their development. Even in infancy and early childhood, this contribution can be seen in a multitude of areas, including attention, language use, and play.

Children first begin to shape their own development through their selection of what to pay attention to. Even newborns prefer to look at things that move and make sounds. This preference helps them learn about important parts of the world, such as people, other animals, and inanimate moving objects. When looking at people, infants’ attention is particularly drawn to faces, especially their mother’s face: Given a choice of looking at a stranger’s face or their mother’s, even 1-month-olds choose to look at Mom (Bartrip, Morton, & de Schonen, 2001). At first, infants’ attention to their mother’s face is not accompanied by any visible emotion, but by the end of the 2nd month, infants smile and coo more when focusing intently on their mother’s face than at other times. This smiling and cooing by the infant elicits smiling and talking by the mother, which elicits further cooing and smiling by the infant, and so on (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005). In this way, infants’ preference for attending to their mother’s face leads to social interactions that can strengthen the mother–infant bond.

Once children begin to speak, usually between 9 and 15 months of age, their contribution to their own development becomes more evident. For example, toddlers (1- and 2-year-olds) often talk when they are alone in a room. Only if children were internally motivated to learn language would they practice talking when no one was present to react to what they are saying. Many parents are startled when they hear this “crib speech” and wonder if something is wrong with a baby who would engage in such odd-seeming behavior. However, the activity is entirely normal, and the practice probably helps toddlers improve their speech.

Young children’s play provides many other examples of how their internally motivated activity contributes to their development. Children play by themselves for the sheer joy of doing so, but they also learn a great deal in the process. Anyone who has seen a baby bang a spoon against the tray of a high chair or intentionally drop food on the floor would agree that, for the baby, the activity is its own reward. At the same time, the baby is learning about the noises made by colliding objects, about the speed at which objects fall, and about the limits of his or her parents’ patience.

13

Young children’s fantasy play seems to make an especially large contribution to their knowledge of themselves and other people. Starting at around age 2 years, children sometimes pretend to be different people in make-believe dramas. For example, they may pretend to be superheroes doing battle with monsters or play the role of parents taking care of babies. In addition to being inherently enjoyable, such play appears to teach children valuable lessons, including how to cope with fears and how to interact with others (Howes & Matheson, 1992; Smith, 2003). Older children’s play, which typically is more organized and rule-bound, teaches them additional valuable lessons, such as the self-control needed for turn-taking, adhering to rules, and controlling one’s emotions in the face of setbacks (Hirsch-Pasek et al., 2008). As we discuss later in the chapter, children’s contributions to their own development strengthen and broaden as they grow older and become increasingly able to choose and shape their environments.

Continuity/Discontinuity: In What Ways Is Development Continuous, and in What Ways Is It Discontinuous?

Continuity/Discontinuity: In What Ways Is Development Continuous, and in What Ways Is It Discontinuous?

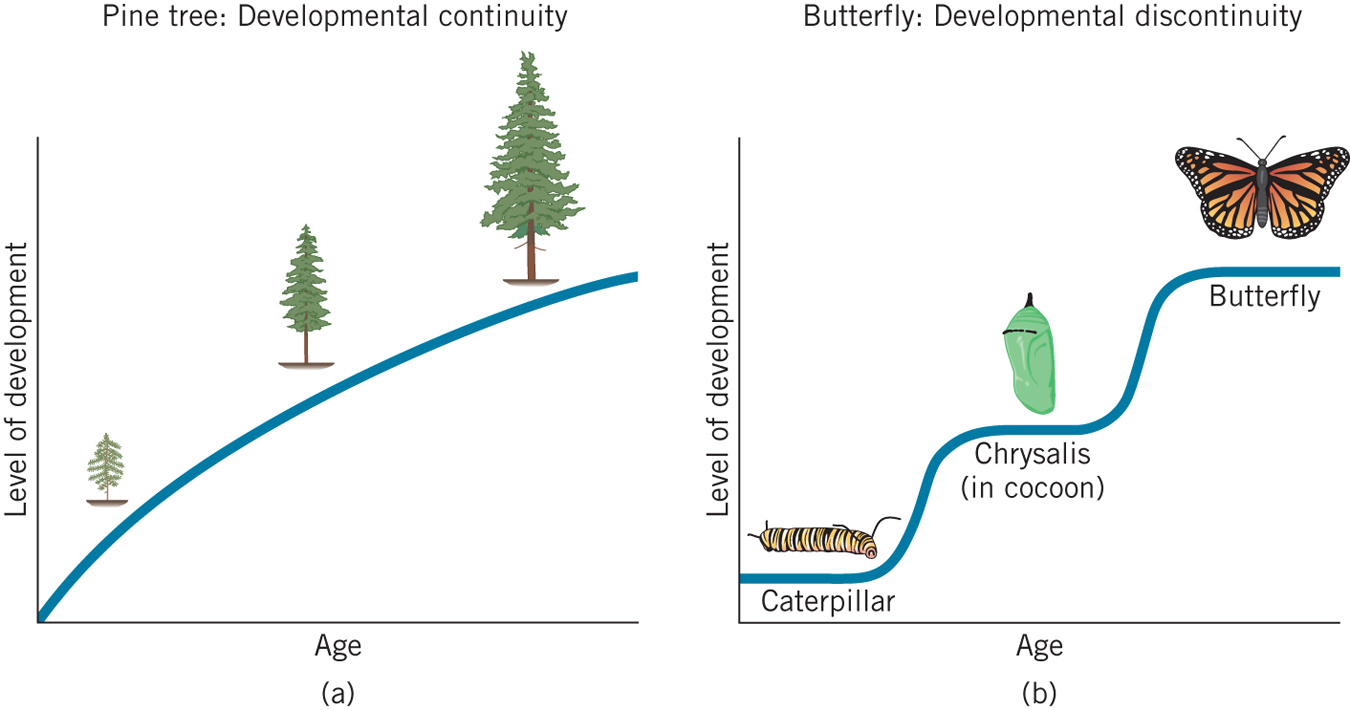

Some scientists envision children’s development as a continuous process of small changes, like that of a pine tree growing taller and taller. Others see the process as a series of sudden, discontinuous changes, like the transition from caterpillar to cocoon to butterfly (Figure 1.2). The debate over which of these views is more accurate has continued for decades.

continuous development  the idea that changes with age occur gradually, in small increments, like that of a pine tree growing taller and taller

the idea that changes with age occur gradually, in small increments, like that of a pine tree growing taller and taller

14

Researchers who view development as discontinuous start from a common observation: children of different ages seem qualitatively different. A 4-year-old and a 6-year-old, for example, seem to differ not only in how much they know but in the whole way they think about the world. To appreciate these differences, consider two conversations between Beth, the daughter of one of the authors, and Beth’s mother. The first conversation took place when Beth was 4 years old, the second, when she was 6. Both conversations occurred after Beth had watched her mother pour all the water from a typical drinking glass into a taller, narrower glass. Here is the conversation that occurred when Beth was 4:

discontinuous development  the idea that changes with age include occasional large shifts, like the transition from caterpillar to cocoon to butterfly

the idea that changes with age include occasional large shifts, like the transition from caterpillar to cocoon to butterfly

Mother: Is there still the same amount of water?

Beth: No.

Mother: Was there more water before, or is there more now?

Beth: There’s more now.

Mother: What makes you think so?

Beth: The water is higher; you can see it’s more.

Mother: Now I’ll pour the water back into the regular glass. Is there the same amount of water as when the water was in the same glass before?

Beth: Yes.

Mother: Now I’ll pour all the water again into the tall thin glass. Does the amount of water stay the same?

Beth: No, I already told you, there’s more water when it’s in the tall glass.

Two years later, Beth responded to the same problem quite differently:

Mother: Is there still the same amount of water?

Beth: Of course!

What accounts for this change in Beth’s thinking? Her everyday observations of liquids being poured cannot have been the reason for it; Beth had seen liquids poured on a great number of occasions before she was 4, yet failed to develop the understanding that the volume remains constant. Experience with the specific task could not explain the change either, because Beth had no further exposure to the task between the first and second conversation. Then why, as a 4-year-old, would Beth be so confident that pouring the water into the taller, narrower glass increased the amount and, as a 6-year-old, be so confident that it did not?

This conservation-of-liquid-quantity problem is actually a classic technique designed to test children’s level of thinking. It has been used with thousands of children around the world, and virtually all the children studied, no matter what their culture, have shown the same type of change in reasoning as Beth did (though usually at somewhat older ages). Furthermore, such age-related differences in understanding pervade children’s thinking. Consider two letters to Mr. Rogers, one sent by a 4-year-old and one by a 5-year-old (Rogers, 1996, pp. 10–11):

15

Dear Mr. Rogers,

I would like to know how you get in the TV.

(Robby, age 4)

Dear Mr. Rogers,

I wish you accidentally stepped out of the TV into my house so I could play with you.

(Josiah, age 5)

Clearly, these are not ideas that an older child would entertain. As with Beth’s case, we have to ask, “What is it about 4- and 5-year-olds that leads them to form such improbable beliefs, and what changes occur that makes such notions laughable to 6- and 7-year-olds?”

stage theories  approaches that propose that development involves a series of discontinuous, age-related phases

approaches that propose that development involves a series of discontinuous, age-related phases

One common approach to answering these questions comes from stage theories, which propose that development occurs in a progression of distinct age-related stages, much like the butterfly example in Figure 1.2b. According to these theories, a child’s entry into a new stage involves relatively sudden, qualitative changes that affect the child’s thinking or behavior in broadly unified ways and move the child from one coherent way of experiencing the world to a different coherent way of experiencing it.

cognitive development  the development of thinking and reasoning

the development of thinking and reasoning

Among the best-known stage theories is Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, the development of thinking and reasoning. This theory holds that between birth and adolescence, children go through four stages of cognitive growth, each characterized by distinct intellectual abilities and ways of understanding the world. For example, according to Piaget’s theory, 2- to 5-year-olds are in a stage of development in which they can focus on only one aspect of an event, or one type of information, at a time. By age 7, children enter a different stage, in which they can simultaneously focus on and coordinate two or more aspects of an event and can do so on many different tasks. According to this view, when confronted with a problem like the one that Beth’s mother presented to her, most 4- and 5-year-olds focus on the single dimension of height, and therefore perceive the taller, narrower glass as having more water. In contrast, most 7- and 8-year-olds consider both relevant dimensions of the problem simultaneously. This allows them to realize that although the column of water in the taller glass is higher, the column also is narrower, and the two differences offset each other.

In the course of reading this book, you will encounter a number of other stage theories, including Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, and Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. Each of these stage theories proposes that children of a given age show broad similarities across many situations and that children of different ages tend to behave very differently.

Such stage theories have been very influential. In the past 20 years, however, many researchers have concluded that most developmental changes are gradual rather than sudden, and that development occurs skill by skill, task by task, rather than in a broadly unified way (Courage & Howe, 2002; Elman et al., 1996; Thelen & Smith, 2006). This view of development is less dramatic than that of stage theories, but a great deal of evidence supports it. One such piece of evidence is the fact that a child often will behave in accord with one proposed stage on some tasks but in accord with a different proposed stage on other tasks (Fischer & Bidell, 2006). This variable level of reasoning makes it difficult to view the child as being “in” either stage.

16

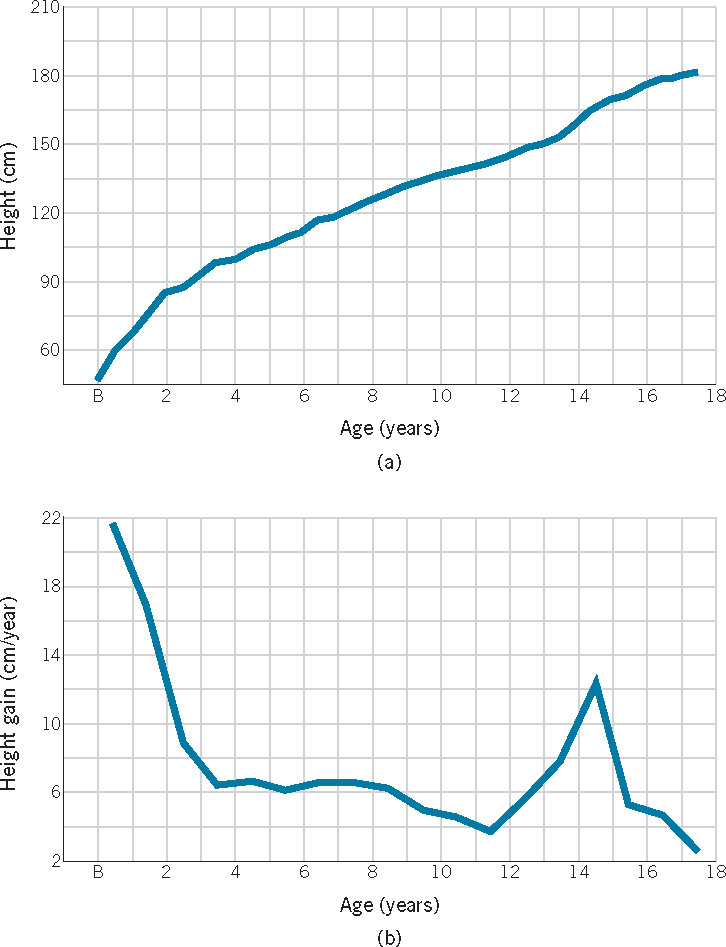

Much of the difficulty in deciding whether development is continuous or discontinuous is that the same facts can look very different, depending on one’s perspective. Consider the seemingly simple question of whether children’s height increases continuously or discontinuously. Figure 1.3a shows a boy’s height, measured yearly from birth to age 18 (Tanner, 1961). When one looks at the boy’s height at each age, development seems smooth and continuous, with growth occurring rapidly early in life and then slowing down.

However, when you look at Figure 1.3b, a different picture emerges. This graph illustrates the same boy’s growth, but it depicts the amount of growth from one year to the next. The boy grew every year, but he grew most during two periods: from birth to age 2½, and from ages 13 to 15. These are the kinds of data that lead people to talk about discontinuous growth and about a separate stage of adolescence that includes a physical growth spurt.

So, is development fundamentally continuous or fundamentally discontinuous? The most reasonable answer seems to be, “It depends on how you look at it and how often you look.” Imagine the difference between the perspective of an uncle who sees his niece every 2 or 3 years and that of the niece’s parents, who see her every day. The uncle will almost always be struck with the huge changes in his niece since he last saw her. The niece will be so different that it will seem that she has progressed to a higher stage of development. In contrast, the parents will most often be struck by the continuity of her development; to them, she usually will just seem to grow up a bit each day. Throughout this book, we will be considering the changes, large and small, sudden and gradual, that have led some researchers to emphasize the continuities in development and others to emphasize the discontinuities.

Mechanisms of Development: How Does Change Occur?

Mechanisms of Development: How Does Change Occur?

Perhaps the deepest mystery about children’s development is expressed by the question “How does change occur?” In other words, what are the mechanisms that produce the remarkable changes that children undergo with age and experience? A very general answer was implicit in the earlier discussion of the theme of nature and nurture. The interaction of genome and environment determines both what changes occur and when those changes occur. The challenge comes in specifying more precisely how any given change occurs.

One particularly interesting analysis of the mechanisms of developmental change involves the roles of brain activity, genes, and learning experiences in the development of effortful attention (e.g., Rothbart, Sheese, & Posner, 2007). Effortful attention involves voluntary control of one’s emotions and thoughts. It includes processes such as inhibiting impulses (e.g., obeying requests to put all of one’s toys away, as opposed to putting some away but then getting distracted and playing with the remaining ones); controlling emotions (e.g., not crying when failing to get one’s way); and focusing attention (e.g., concentrating on one’s homework despite the inviting sounds of other children playing outside). Difficulty in exerting effortful attention is associated with behavioral problems, weak math and reading skills, and mental illness (Blair & Razza, 2007; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

17

Studies of the brain activity of people performing tasks that require control of thoughts and emotions show that connections are especially active between the anterior cingulate, a brain structure involved in setting and attending to goals, and the limbic area, a part of the brain that plays a large role in emotional reactions (Etkin et al., 2006). Connections between brain areas such as the anterior cingulate and the limbic area develop considerably during childhood, and their development appears to be one mechanism that underlies improving effortful attention during childhood (Rothbart et al., 2007).

neurotransmitters  chemicals involved in communication among brain cells

chemicals involved in communication among brain cells

What role do genes and learning experiences play in influencing this mechanism of effortful attention? Specific genes influence the production of key neurotransmitters—chemicals involved in communication among brain cells. Variations among children in these genes are associated with variations in the quality of performance on tasks that require effortful attention (Canli et al., 2005; Diamond et al., 2004; Rueda et al., 2005). These genetic influences do not occur in a vacuum, however. As noted in the discussion of epigenetics, the environment plays a crucial role in the expression of genes. Infants with a particular form of one of the genes in question show differences in effortful attention related to the quality of parenting they receive, with lower-quality parenting being associated with lower ability to regulate attention (Sheese et al., 2007). Among children who do not have that form of the gene, quality of parenting has less effect on effortful attention.

Children’s experiences also can change the wiring of the brain system that produces effortful attention. Rueda and colleagues (2005) presented 6-year-olds with a 5-day training program that used computerized exercises to improve capacity for effortful attention. Examination of electrical activity in the anterior cingulate indicated that those 6-year-olds who had completed the computerized exercises showed improved effortful attention. These children also showed improved performance on intelligence tests, which makes sense given the sustained effortful attention required by such tests. Thus, the experiences that children encounter influence their brain processes and gene expression, just as brain processes and genes influence children’s reactions to experiences. More generally, a full understanding of the mechanisms that produce developmental change requires specifying how genes, brain structures and processes, and experiences interact.

The Sociocultural Context: How Does the Sociocultural Context Influence Development?

The Sociocultural Context: How Does the Sociocultural Context Influence Development?

sociocultural context  the physical, social, cultural, economic, and historical circumstances that make up any child’s environment

the physical, social, cultural, economic, and historical circumstances that make up any child’s environment

Children grow up in a particular set of physical and social environments, in a particular culture, under particular economic circumstances, at a particular time in history. Together, these physical, social, cultural, economic, and historical circumstances interact to constitute the sociocultural context of a child’s life. This sociocultural context influences every aspect of children’s development.

A classic depiction of the components of the sociocultural context is Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) bioecological model (discussed in depth in Chapter 9). The most obviously important component of children’s sociocultural contexts is the people with whom they interact—parents, grandparents, brothers, sisters, day-care providers, teachers, friends, classmates, and so on—and the physical environment in which they live—their house, day-care center, school, neighborhood, and so on. Another important but less tangible component of the sociocultural context is the institutions that influence children’s lives: educational systems, religious institutions, sports leagues, social organizations (such as boys’ and girls’ clubs), and so on.

18

Yet another important set of influences are the general characteristics of the child’s society: its economic and technological advancement; its values, attitudes, beliefs, and traditions; its laws and political structure; and so on. For example, the simple fact that most toddlers and preschoolers growing up in the United States today go to child care outside their homes reflects a number of these less tangible sociocultural factors, including:

- The historical era (50 years ago, far fewer children in the United States attended child-care centers)

- The economic structure (there are far more opportunities today for women with young children to work outside the home)

- Cultural beliefs (for example, that receiving child care outside the home does not harm children)

- Cultural values (for example, the value that mothers of young children should be able to work outside the home if they wish).

Attendance at child-care centers, in turn, partly determines the people children meet and the activities in which they engage.

One method that developmentalists use to understand the influence of the sociocultural context is to compare the lives of children who grow up in different cultures. Such cross-cultural comparisons often reveal that practices that are rare or nonexistent in one’s own culture are common in other cultures. The following comparison of young children’s sleeping arrangements in different societies illustrates the value of such cross-cultural research.

In most families in the United States, newborn infants sleep in their parents’ bedroom, either in a crib or in the same bed. However, when infants are 2 to 6 months old, parents usually move them to another bedroom where they sleep alone (Greenfield, Suzuki, & Rothstein-Fisch, 2006). This seems natural to most people raised in the United States, because it is how we and others whom we know were raised. From a worldwide perspective, however, such sleeping arrangements are highly unusual. In most other societies, including economically advanced nations such as Italy, Japan, and South Korea, babies almost always sleep in the same bed as their mother for the first few years, and somewhat older children also sleep in the same room as their mother, sometimes in the same bed (e.g., Nelson, Schiefenhoevel, & Haimerl, 2000; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Where does this leave the father? In some cultures, the father sleeps in the same bed with mother and baby; in others, he sleeps in a separate bed or in a different room.

How do these differences in sleeping arrangements affect children? To find out, researchers interviewed mothers in middle-class U.S. families in Salt Lake City, Utah, and in rural Mayan families in Guatemala (Morelli et al., 1992). These interviews revealed that by age 6 months, the large majority of the U.S. children had begun sleeping in their own bedroom. As the children grew out of infancy, the nightly separation of child and parents became a complex ritual, surrounded by activities intended to comfort the child, such as telling stories, reading children’s books, singing songs, and so on. About half the children were reported as taking a comfort object, such as a blanket or teddy bear, to bed with them.

19

In contrast, interviews with the Mayan mothers indicated that their children typically slept in the same bed with them until the age of 2 or 3 years and continued to sleep in the same room with them for years thereafter. The children usually went to sleep at the same time as their parents. None of the Mayan parents reported bedtime rituals, and almost none reported their children taking comfort objects, such as dolls or stuffed animals, to bed with them.

Why do sleeping arrangements differ across cultures? Interviews with the Mayan and U.S. parents indicated that the crucial consideration for them in determining sleeping arrangements was cultural values. Mayan culture prizes interdependence among people. The Mayan parents expressed the belief that having a young child sleep with the mother is important for developing a good parent–child relationship, for avoiding the child’s becoming distressed at being alone, and for helping parents spot any problems the child is having. They often expressed shock and pity when told that infants in the United States typically sleep separately from their parents (Greenfield et al., 2006). In contrast, U.S. culture prizes independence and self-reliance, and the U.S. mothers expressed the belief that having babies and young children sleep alone promotes these values, as well as allowing intimacy between husbands and wives (Morelli et al., 1992). These differences illustrate both how practices that strike us as natural may differ greatly across cultures and how the simple conventions of everyday life often reflect deeper values.

socioeconomic status (SES)  a measure of social class based on income and education

a measure of social class based on income and education

Contexts of development differ not just between cultures but also within them. In modern multicultural societies, many contextual differences are related to ethnicity, race, and socioeconomic status (SES)—a measure of social class that is based on income and education. Virtually all aspects of children’s lives—from the food they eat to the parental discipline they receive to the games they play—vary with ethnicity, race, and SES.

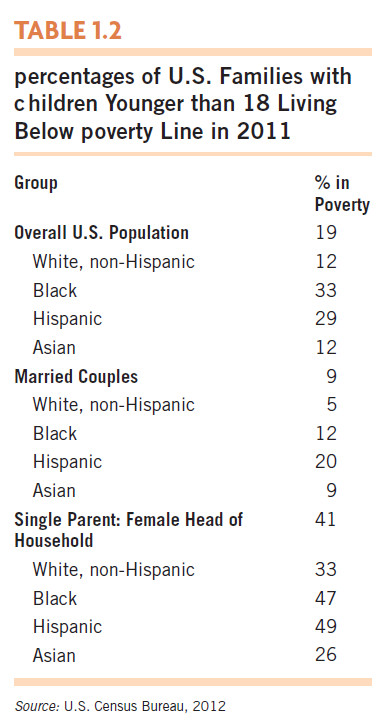

The socioeconomic context exerts a particularly large influence on children’s lives. In economically advanced societies, including the United States, most children grow up in comfortable circumstances, but millions of other children do not. In 2011, about 19% of U.S. families with children had incomes below the poverty line (in that year, $18,530 for a family of three with one adult and two children). In absolute numbers, that translates into about 16 million children growing up in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). As shown in Table 1.2, poverty rates are especially high in Black and Hispanic families and in families of all races that are headed by single mothers. Poverty rates are also very high among the roughly 25% of children in the United States who are either immigrants or the children of immigrants—roughly twice as high as among children of native-born parents (Hernandez, Denton, & Macartney, 2008; Smeeding, 2008).

Children from poor families tend to do less well than other children in many ways (G. W. Evans et al., 2005; Morales & Guerra, 2006). In infancy, they are more likely to have serious health problems. In childhood, they are more likely to have social/emotional and behavioral problems. Throughout childhood and adolescence, they tend to have smaller vocabularies, lower IQs, and lower math and reading scores on standardized achievement tests. In adolescence, they are more likely to have a baby or drop out of school (G. W. Evans et al., 2005; Luthar, 1999; McLoyd, 1998).

These negative outcomes are not surprising when we consider the huge array of disadvantages that poor children face. Compared with children who grow up in more affluent circumstances, they are more likely to live in dangerous neighborhoods, to attend inferior day-care centers and schools, and to be exposed to high levels of air and water pollution (Dilworth-Bart & Moore, 2006; G. W. Evans, 2004). In addition, their parents read to them less, talk to them less, provide fewer books in the home, and are less involved in their schooling. Poor children also are more likely than affluent children to grow up in single-parent homes or to be raised by neither biological parent. The accumulation of these disadvantages, rather than any single one of them, seems to be the greatest obstacle to poor children’s successful development (Luthar, 2006; Morales & Guerra, 2006).

20

And yet as we saw in Werner’s study of the children of Kauai, described at the beginning of the chapter, many children do overcome the obstacles that poverty presents. Such resilient children tend to have three characteristics: (1) positive personal qualities, such as high intelligence, an easygoing personality, and an optimistic outlook on the future; (2) a close relationship with at least one parent; and (3) a close relationship with at least one adult other than their parents, such as a grandparent, teacher, coach, or family friend (Chen & Miller, 2012; Masten, 2007). Thus, although poverty poses serious obstacles to successful development, many children do surmount the challenges—usually with the help of adults in their lives.

Individual Differences: How Do Children Become So Different from One Another?

Individual Differences: How Do Children Become So Different from One Another?

Anyone who has experience with children is struck by their uniqueness—their differences not only in physical appearance but in everything from activity level and temperament to intelligence, persistence, and emotionality. These differences among children emerge quickly. Some infants in their first year are shy, others outgoing. Some infants play with or look at objects for prolonged periods; others rapidly shift from activity to activity. Even children in the same family often differ substantially, as you probably already know if you have siblings.

Scarr (1992) identified four factors that can lead children from a single family (as well as children from different families) to turn out very different from one another:

- Genetic differences

- Differences in treatment by parents and others

- Differences in reactions to similar experiences

- Different choices of environments

The most obvious reason for differences among children is that, except for identical twins, every individual is genetically unique. All other siblings (including fraternal twins) share 50% of their genes and differ in the other 50%.

A second major source of variation among children is differences in the treatment they receive from parents and other people. This differential treatment is often associated with preexisting differences in the children’s characteristics. For example, parents tend to provide more sensitive care to easygoing infants than to difficult ones; by the second year, parents of difficult children are often angry with them even when the children have done nothing wrong in the immediate situation (van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994). Teachers, likewise, tend to provide positive attention and encouragement to pupils who are learning well and are well behaved, but with pupils who are doing poorly and are disruptive, they tend to be openly critical and to deny the pupils’ requests for special help (Good & Brophy, 1996).

21

In addition to being shaped by objective differences in the treatment they receive, children also are influenced by their subjective interpretations of the treatment. A classic example occurs when each of a pair of siblings feels that their parents favor the other. Siblings also often react differently to events that affect the whole family. In one study, 69% of negative events, such as parents’ being laid off or fired, elicited fundamentally different reactions from siblings (Beardsall & Dunn, 1992). Some children were very concerned at a parent’s loss of a job; others were sure that everything would be okay.

A fourth major source of differences among children relates to the previously discussed theme of the active child: As children grow older, they increasingly choose activities and friends for themselves and thus influence their own subsequent development. They may also accept or choose niches for themselves: within a family, one child may become “the smart one,” another “the popular one,” another “the bad one,” and so on (Scarr & McCartney, 1983). A child labeled by family members as “the smart one” may strive to live up to the label; so, unfortunately, may a child labeled “the troublemaker.”

As discussed in the section on nature and nurture and in the section on mechanisms of development, differences in biology and experience interact in complex ways to create the infinite diversity of human beings. Thus, a study of 11- to 17-year-olds found that the grades of children who were highly engaged with school changed in more positive directions than would have been predicted by their genetic background or family environments alone (Johnson, McGue, & Iacono, 2006). The same study revealed that children of high intelligence were less negatively affected by adverse family environments than were other children. Thus, children’s genes, their treatment by other people, their subjective reactions to their experiences, and their choice of environments interact in ways that contribute to differences among children, even ones in the same family.

Research and Children’s Welfare: How Can Research Promote Children’s Well-Being?

Research and Children’s Welfare: How Can Research Promote Children’s Well-Being?

Improved understanding of child development often leads to practical benefits. Several examples have already been described, including the program for helping children deal with their anger and the recommendations for fostering valid eyewitness testimony from young children.

Another type of practical benefit arising from child-development research involves educational innovations. One fascinating example comes from studies of how children’s beliefs about intelligence influence their learning. Carol Dweck and her colleagues (Dweck, 2006; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) have found that some children (and adults) believe that intelligence is a fixed entity. They see each person as having a certain amount of intelligence that is set at birth and cannot be changed by experience. Other children (and adults) believe that intelligence is a changeable characteristic that increases with learning and that the time and effort people put into learning is the key determinant of their intelligence.

People who believe that intelligence increases with learning tend to react to failure in more effective ways (Dweck, 2006). When they fail to solve a problem, they more often persist on the task and try harder. Such persistence in the face of failure is an important quality. As the great British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said, “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.” In contrast, people who believe that intelligence is a fixed entity tend to give up when they fail, because they think the problem is too hard for them.

22

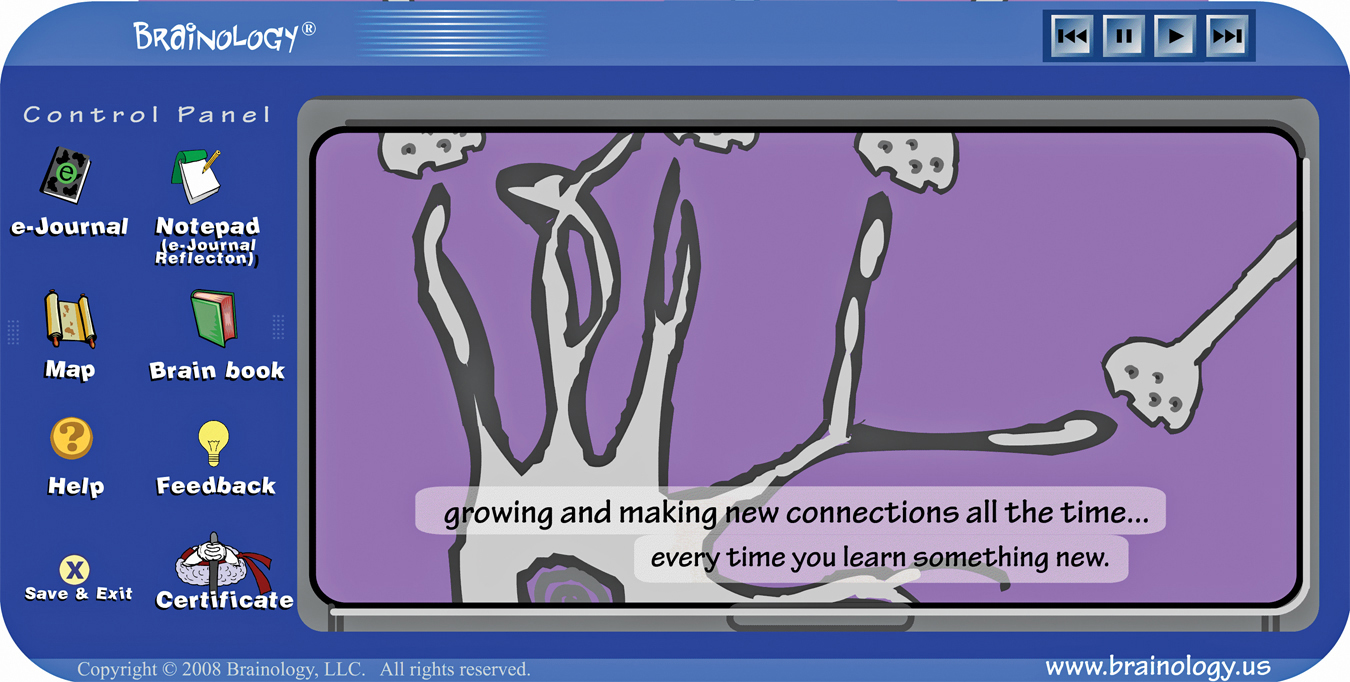

Building on this research regarding the relation between beliefs about intelligence and persistence in the face of difficulty, Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck (2007) devised an effective educational program for middle school students from low-income backgrounds. They presented randomly selected students with research findings about how learning alters the brain in ways that improve subsequent learning and thus “makes you smarter.” Other randomly selected students from the same classrooms were presented with research findings about how memory works. The investigators predicted that the students who were told about the effects that learning has on the brain would change their beliefs about intelligence in ways that would help them persevere in the face of failure. In particular, the changed beliefs were expected to improve students’ learning of mathematics, an area in which children often experience initial failure.

This prediction was borne out. Children who were presented information about how learning changes the brain and enhances intelligence subsequently improved their math grades, whereas the other children did not. Children who initially believed that intelligence was an inborn, unchanging quality but who came to believe that intelligence reflected learning showed especially large improvements. Perhaps most striking, when the children’s teachers, who did not know which type of information each child had received, were asked if any of their students had shown unusual improvement in motivation or performance, the teachers cited more than three times as many students who had been given information about how learning builds intelligence.

In subsequent chapters, we review many additional examples of how child development research is being used to promote children’s welfare.

review:

The modern field of child development is in large part an attempt to answer a small set of fundamental questions about children. These include:

- How do nature and nurture jointly contribute to development?

- How do children contribute to their own development?

- Is development best viewed as continuous or discontinuous?

- What mechanisms produce development?

- How does the sociocultural context influence development?

- Why are children so different from one another?

- How can we use research to improve children’s welfare?