3a Exploring a topic

Contents:

The point is so simple that it’s easy to forget: you write best about topics you know well. One of the most important parts of the entire writing process, therefore, is choosing a topic that will engage your strengths and your interests, surveying what you know about it, and determining what you need to find out.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming

Used widely in business and industry, brainstorming involves tossing out your ideas—either orally or in writing—to discover new ways to approach a topic. You can brainstorm with others or by yourself.

- Within five or ten minutes, list every word or phrase that comes to mind about the topic. Jot down key words and phrases, not sentences. No one has to understand the list but you. Don’t worry about whether or not something will be useful—just list as much as you can in this brief span of time.

- If little occurs to you, try calling out or writing down thoughts about the opposite side of your topic. If you are trying, for instance, to think of reasons to raise tuition and are coming up blank, try concentrating on reasons to reduce tuition. Once you start generating ideas in one direction, you’ll find that you can usually move back to the other side fairly easily.

- When the time is up, stop and read over the lists you’ve made. If anything else comes to mind, add it to the list. Then reread the list. Look for patterns of interesting ideas or for one central idea.

Emily Lesk’s brainstorming

Emily Lesk, the student whose work appears in Chapters 2–4, did some brainstorming with her classmates on the general topic the class was working on: an aspect of American identity affected by one or more media. Here are some of the notes Emily made during the brainstorming session:

- “American identity”—Don’t Americans have more than one identity?

- Picking a kind of media could be hard. I like clever ads. Maybe advertising and its influence on us?

- Wartime advertising; recruiting ads that promote patriotic themes.

- Look at huge American companies like Walmart and McDonald’s and how their ads affect the way we view ourselves. Not sure what direction to take. . . .

Freewriting and looping

Freewriting and looping

Freewriting is a method of exploring a topic by writing about it for a period of time without stopping.

- Write for ten minutes or so. Think about your topic, and let your mind wander freely. Write down everything that occurs to you—in complete sentences as much as possible—but don’t worry about spelling or grammar. If you get stuck, write anything—just don’t stop.

- When the time is up, look at what you have written. Much of this material will be unusable, but you may still discover some important insights and ideas.

If you like, you can continue the process by looping: find the central or most intriguing thought from your freewriting, and summarize it in a single sentence. Freewrite for five more minutes on the summary sentence, and then find and summarize the central thought from the second “loop.” Keep this process going until you discover a clear angle or something about the topic that you can pursue.

Emily Lesk’s freewriting

Here is a portion of the freewriting Emily Lesk did to focus her ideas after the brainstorming session:

Media and effect on American identity. What media do I want to write about? That would make a big difference—television, radio, Internet—they’re all different ways of appealing to Americans. TV shows that say something about American identity? What about magazine or TV advertising? Advertising tells us a lot about what it means to be American. Think about what advertising tells us about American identity. What ads make me think “American”? And why?

Clustering

Clustering

Clustering is a way of generating ideas using a visual scheme or chart. It is especially helpful for understanding the relationships among the parts of a broad topic and for developing subtopics. You may have a software program for clustering. If not, follow these steps:

- Write your topic in the middle of a piece of paper, and circle it.

- In a ring around the topic circle, write what you see as the main parts of the topic. Circle each part, and draw a line from it to the topic.

- Think of more ideas, examples, facts, or other details relating to each main part. Write each of these near the appropriate part, circle each one, and draw a line from it to the part.

- Repeat this process with each new circle until you can’t think of any more details. Some trails may lead to dead ends, but you will still have many useful connections among ideas.

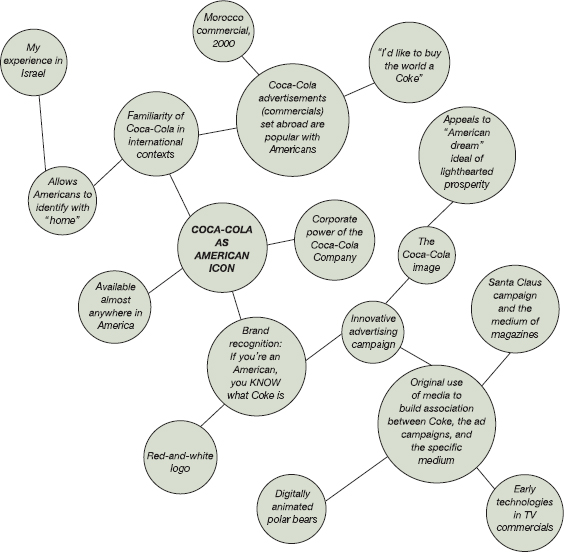

Emily Lesk’s clustering

When Emily Lesk asked herself what things made her think “American,” one of her first answers was “Coca-Cola.” So later in her planning and exploring process, she decided to work on the topic of Coca-Cola advertising and American identity (3b and c). After finding a large Coca-Cola advertising archive, Emily used clustering to help focus her emerging ideas. Her clustering appears here. (Remember that you may want to explore aspects of your ideas more than once—and exploring may be helpful at any stage as you plan and draft a piece of writing.)

Drawing or making word pictures

Drawing or making word pictures

If you’re someone who prefers visual thinking, you might either create a drawing about the topic or use figurative language—such as similes and metaphors—to describe what the topic resembles. Working with pictures or verbal imagery can sometimes also help illuminate the topic or uncover some of your unconscious ideas or preconceptions about it.

- If you like to draw, try sketching your topic. What images do you come up with? What details of the drawing attract you most? What would you most like to expand on? A student planning to write an essay on her college experience began by thinking with pencils and pen in hand. Soon she found that she had drawn a vending machine several times, with different products and different ways of inserting money to extract them (one of her drawings appears here). Her sketches led her to think about what it might mean to see an education as a product. Even abstract doodling can lead you to important insights about the topic and to focus your topic productively.

- Look for figurative language—metaphors and similes—that your topic resembles. Try jotting down three or four possibilities, beginning with “My subject is ________” or “My subject is like ________.” A student working on the subject of genetically modified crops came up with this simile: “Genetically modified foods are like empty calories: they do more harm than good.” This exercise made one thing clear to this student writer: she already had a very strong bias that she would need to watch out for while developing her topic.

Play around a bit with your topic. Ask, for instance, “If my topic were a food (or a song or a movie or a video game), what would it be, and why?” Or write a Facebook status update about your topic, or tweet a friend or an interested group saying—within 140 characters—why this topic appeals to you. Such exercises can get you out of the rut of everyday thinking and help you see your topic in a new light.

Looking at images and videos

Looking at images and videos

Searching images or browsing videos may spark topic ideas or inspire questions that you want to explore. If you plan to create a highly visual project—a video essay or slide presentation, for instance—you will probably need to decide what you want to show your audience before you plan the words that will accompany the images.

Keeping a reflective journal or private blog

Keeping a reflective journal or private blog

Writers often get their best ideas by jotting down or recording thoughts that come to them randomly. You can write in a notebook, record audio notes on a phone, store pictures and video files on a private blog—some writers even keep a marker and writing board on the shower wall so that they can write down the ideas that come to them while bathing! As you begin thinking about your assignment, taking time to record what you know about your topic and what still puzzles you may lead you to a breakthrough or help you articulate your main idea.

Asking questions

Asking questions

Another basic strategy for exploring a topic and generating ideas is simply to ask and answer questions. Here are several widely used sets of questions to get you started, either on your own or with one or two others.

Questions to describe a topic

Originally developed by Aristotle, the following questions can help you explore a topic by carefully and systematically describing it:

- What is it? What are its characteristics, dimensions, features, and parts? What do your senses tell you about it?

- What caused it? What changes occurred to create your topic? How is it changing? How will it change?

- What is it like or unlike? What features differentiate your topic from others? What analogies can you make about your topic?

- What larger system is the topic a part of? How does your topic relate to this system?

- What do people say about it? What reactions does your topic arouse? What about the topic causes those reactions?

Questions to explain a topic

The well-known questions who, what, when, where, why, and how, widely used by news reporters, are especially helpful for explaining a topic.

- Who is doing it?

- What is at issue?

- When does it take place?

- Where is it taking place?

- Why does it occur?

- How is it done?

Questions to persuade

When your purpose is to persuade or convince, the following questions, developed by philosopher Stephen Toulmin, can help you think analytically about your topic (8e and 9j):

- What claim are you making about your topic?

- What good reasons support your claim?

- What valid underlying assumptions support the reasons for your claim?

- What backup evidence can you find for your claim?

- What refutations of your claim should you anticipate?

- In what ways should you qualify your claim?

Consulting sources

Consulting sources

At the library and on the Internet, browse for a topic you want to learn more about. If you have a short list of ideas, follow links from one interesting article to another to see what you can find, or do a quick check of reference works to get overviews of the topics. You can begin with a general encyclopedia or a specialized reference work that focuses on a specific area, such as music or psychology (11b). You can also use Wikipedia as a starting point: take a look at entries that relate to your topic, especially noting the sources they list. While you should not rely on Wikipedia alone, it is a highly accessible way to begin your research.

Collaborating

Collaborating

As you explore your topic, remember that you can gain valuable insights from others. Many writers say that they get their best ideas in conversation with other people. If you talk with friends or roommates about your topic, at the very least you will hear yourself describe the topic and your interest in it; this practice will almost certainly sharpen your understanding of what you are doing. You can also seek out Facebook groups, Web forums, or other networking sites as places to share your thinking on a topic and find inspiration.