What Is an Argument?

An argument is a stated position, with support for or against an idea or issue. In an argument, you ask listeners to accept a conclusion about some state of affairs, support it with evidence, and provide reasons demonstrating that the evidence supports the claim.

You have already seen one type of classic argument—the syllogism—in Chapter 24. Recall that in a formal syllogism, if both premises are true the conclusion must also be true. But most claims in a persuasive speech address issues that cannot be proved or disproved absolutely. Instead, they lead to conclusions that can be strong or weak; that is, listeners may decide the claim is probably true, largely untrue, or somewhere in between. The core elements of such an argument consist of a claim, evidence, and warrants:1

- The claim states the speaker’s conclusion about some state of affairs.

- The evidence substantiates the claim.

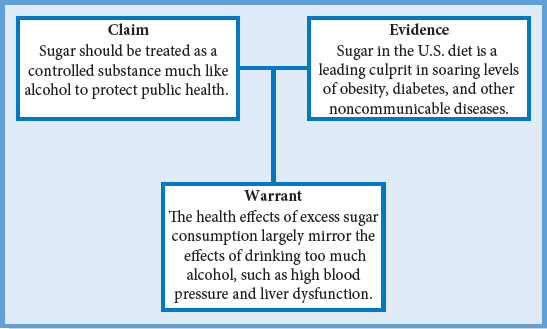

- The warrants provide reasons or justifications for why the claim follows from the evidence; it may be stated or implied (see Figure 25.1).

Stating a Claim

To state a claim (also called a proposition) is to declare a state of affairs. Claims answer the question “What are you trying to prove?” If you want to convince audience members to purchase food and other goods from producers who are fair-trade certified, you might make this claim: “By purchasing goods from fair-trade producers, you can help ensure that farmers and workers are justly compensated.” This claim asserts that buying fair-trade products will help farmers and workers. But unless your listeners already agree with the claim, it’s unlikely that they’ll accept it at face value. To make the claim convincingly, the speaker must provide proof, or evidence, in support of the claim.

Providing Evidence

Every key claim you make in a speech must be supported with evidence, or supporting material that provides grounds for belief. Evidence answers the question, “What is your proof for the claim?” In the speech about fair-trade certified products, you might provide statistics showing the number of farmers and workers that the certification program actually benefits. You might then couple these data with testimony from some farmers and workers (see Chapter 8, “Developing Supporting Material”).

The goal in using evidence is to make a claim more acceptable, or believable, to the audience. If the evidence itself is believable, then the claim is more likely to be found acceptable by the audience.

Providing Reasons

Warrants, the third component of arguments, help to support a claim and to substantiate in the audience’s mind the link between the claim and the evidence. A warrant is a line of reasoning that allows audience members to evaluate whether in fact the evidence does support the claim. It shows why the evidence is valid for the claim, or warranted. Note that the explanation of warrant closely follows the definition of reasoning itself: “the process of drawing inferences or conclusions from evidence.”2 For listeners to accept the argument, the connection between the claim and the evidence must be made clear and justified in their minds; one or more warrants serve this purpose. For example, a warrant behind the claim that “Purchasing fair-trade certified products helps the farmers and workers who produce them” might be that people want what’s fair for others:

| CLAIM: | Purchasing products certified as fair trade assures just compensation to the farmers and workers who produce them. |

| EVIDENCE: | Mose Rene, a banana farmer from St. Lucia, says that his local group of 80 farmers signed up to Fair trade at the point when they were thinking of stopping producing bananas; they just couldn’t compete. Now, under Fair trade, the farmers get almost double the rate for a box of bananas.3 |

| WARRANT: | People want what’s fair for others, including that they are justly compensated. |

Warrants reflect the assumptions, beliefs, or principles that underlie the claim. Critically, if the audience does not accept these underlying assumptions, they will not accept your argument. If, for instance, your claim addresses an emotionally charged topic such as “Prayer should be permitted in public schools,” audience members’ underlying beliefs about the separation of church and state may be such that no amount of evidence would change their minds. Thus it is crucial when preparing claims for an audience to (1) identify the reasoning behind your claim and (2) consider whether the audience is likely to accept it.4 The more controversial your claims, the more important this step becomes. For less controversial topics, the warrants may be shared by most people and thus not necessary to state.5 For example, when urging people to take care of their teeth, the warrant may be as straightforward as “You want to protect your health.”

Diagramming argument allows you to visualize how evidence and warrants can be presented in support of your claim. Figure 25.1 illustrates the three core components of an argument. As you consider formulating an argument, try to diagram it in a similar fashion:

- Write down the claim.

- List each possible piece of evidence you have in support of the claim.

- Write down the corresponding warrants, or justifications, that link the evidence to the claim.

ETHICALLY SPEAKING

Engaging in Arguments in the Public Arena

Because the potential to do harm is greater when more people are involved in a communication event, public discourse carries a greater scope of responsibility and accountability than does private discourse. Consider the following guidelines when engaged in arguments in the public arena:

- Arguing does not mean “fighting,” name-calling, or attacking personalities (see “Fallacies in Reasoning”)

- Arguing involves sound reasoning about issues

- Arguing strives for accuracy in the claims made and the evidence offered

- Arguing responds to alternative or opposing views with sound counter-claims

- Arguing begins and ends with civil discourse

Radu Bercan/Shutterstock