Becoming an Effective Group Participant

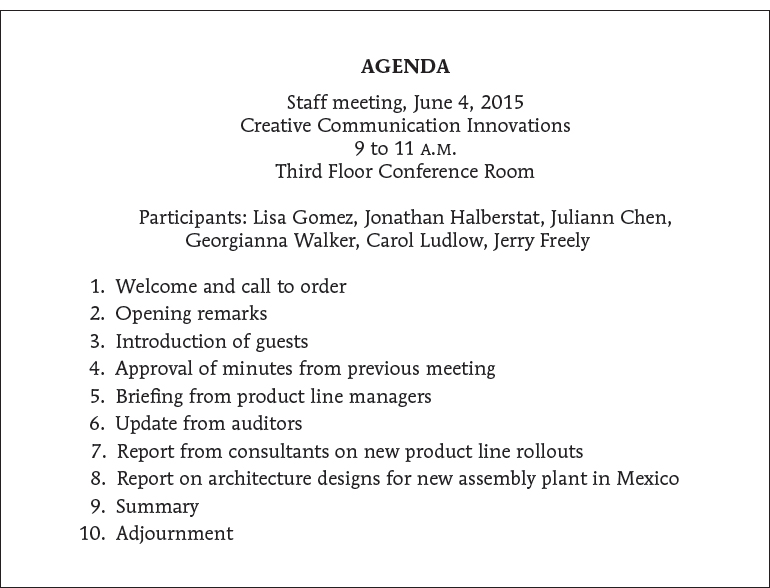

How well or poorly you meet the objectives of the group—whether to coordinate a team presentation or meet some other purpose—is largely a function of how you keep sight of the group’s goals and avoid behaviors that detract from these goals. The more you use the group’s goals as a steadying guide, the less likely you are to be diverted from your real responsibilities as a participant. Setting an agenda can help participants stay on track by identifying the items to be accomplished during a meeting; often it will specify time limits for each item of business.3 Figure 29.1 offers an example of an agenda.

Plan on Assuming Dual Roles

In a group, you will generally assume dual roles: a task role and an interpersonal role. Task roles are the hands-on roles that directly relate to the group’s accomplishment of its objectives. Examples include “recording secretary” (takes notes), “moderator” (facilitates discussion), “initiator” (helps the group get moving by generating new ideas, offering solutions), and “information seeker” (seeks clarification and input from the group).4 Members also adopt various social or interpersonal roles, based on individual personality traits and how they relate in the group. These “relational” roles facilitate group interaction and include, for example, “harmonizer” (reduces tension) and “gatekeeper” (keeps the discussion moving and gets everyone moving).5

Task roles and interpersonal roles help the group maintain cohesion and achieve its mission. Sometimes, however, group members focus on individual needs irrelevant to the tasks on hand. Antigroup roles—such as “floor hogger” (not allowing others to speak), “blocker” (being overly negative about group ideas; raising issues that have been settled), and “recognition seeker” (acts to call attention to oneself rather than to group tasks)—do not further the group’s goals and should be avoided.

Center Disagreement around Issues

Whenever people come together to consider an important issue, conflict is inevitable. But conflict doesn’t have to be destructive. In fact, the best decisions are usually those that emerge from productive conflict.6 In productive conflict, group members clarify questions, challenge ideas, present counterexamples, consider worst-case scenarios, and reformulate proposals. After a process like this, the group can be confident that its decision has been put to a good test. Productive conflict centers disagreements around issues rather than personalities. In personal-based conflict, members argue about one another instead of about the issues, wasting time and impairing motivation. In contrast, issues-based conflict allows members to test and debate ideas and potential solutions. It requires each member to ask tough questions, press for clarification, and present alternative views.7

Resist Groupthink

For groups to be truly effective, members eventually need to form a collective mind8—that is, engage in communication that is critical, careful, consistent, and conscientious.9 Maintaining a collective mind obviously requires the careful management of issues-based and personal-based conflict, but at the same time group members must avoid the tendency to think too much alike. Groupthink is the tendency to accept information and ideas without subjecting them to critical analysis.10

Groups prone to groupthink typically exhibit these behaviors:

- Participants reach a consensus and avoid conflict in order not to hurt others’ feelings, but without genuinely agreeing.

- Members who do not agree with the majority of the group feel pressured to conform.

- Disagreement, tough questions, and counterproposals are discouraged.

- More effort is spent justifying the decision than testing it.

Research suggests that groups can reach the best decisions by adopting two methods of argument: devil’s advocacy (arguing for the sake of raising issues or concerns about the idea under discussion) or dialectical inquiry (devil’s advocacy that goes a step further by proposing a countersolution to the idea).11 Both approaches help expose underlying assumptions that may be preventing participants from making the best decision. As you lead a group, consider how you can encourage both methods of argument.

Leaders and group members can also be helpful by raising the following questions to open up the discussion:

- Do group members avoid examining new information from outside sources?

- Do group members avoid forming contingency plans for when their first (and only) decision fails?

- Does the leader dampen open discussion of ideas?

- Do members criticize others when new options are raised?12