Contribute to Positive Public Discourse

An important measure of ethical speaking is whether it contributes something positive to public discourse—speech involving issues of importance to the larger community, such as debates on campus about U.S military involvement in the Middle East or on the need to take action to slow climate change.

What might constitute a positive contribution to public debates of this nature? Perhaps most important is the advancement of constructive goals. An ethical speech appeals to the greater good rather than to narrow self-interest. Speaking merely to inflame and demean others, on the other hand, degrades the quality of public discourse. Consider the case of the conservative commentator Rush Limbaugh, who once called a Georgetown University law student a “slut” and “prostitute” for criticizing the Jesuit (Catholic) university because it did not offer contraceptive coverage for students.10

Limbaugh’s invective, or verbal attack, targeted a person instead of the issue at hand (ad hominem attack). This and other fallacies of reasoning (see Chapter 25) serve as conversation stoppers—speech designed to discredit, demean, and belittle those with whom one disagrees. Conversation stoppers and other forms of attack breach the acceptable “rules of engagement” for public conversations. As communication scholar W. Barnett Pearce explains, the concept of the rules of engagement, originally used as a military term, can be applied to the ways we relate to one another in the public arena: “Comparable to the orders about the circumstances in which soldiers may use their weapons are the rights and responsibilities to speak, to speak the truth, to disclose one’s purposes, to respond to others, to respond coherently, to listen, and to understand.”11

SELF-ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST

IDENTIFYING VALUES

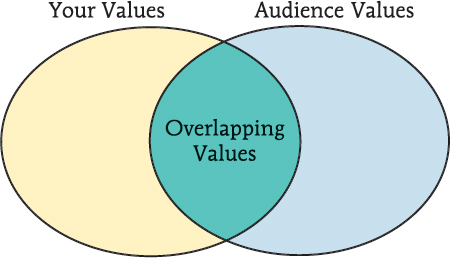

As a way of uncovering where your values lie, rank each item from 1 to 10 (from least to most important). From these, select your top five values and write them down in the circle labeled “Your Values” in Figure 5.1. Repeat the exercise, but this time rank each value in terms of how important you think it is to your audience. Select the top five of these values and place them in the circle labeled “Audience Values.” Finally, draw arrows to the overlapping area to indicate where your highest values (of those listed) coincide with those you think are most important to your listeners.

| Terminal Values: (States of being you consider important | Instrumental Values: (Characteristics you value in yourself and others) |

| A comfortable life | Ambitious |

| An exciting life | Broadminded |

| A sense of accomplishment | Capable |

| A world at peace | Cheerful |

| A world of beauty | Clean |

| Equality | Courageous |

| Family security | Forgiving |

| Freedom | Helpful |

| Happiness | Honest |

| Inner harmony | Imaginative |

| Mature love | Independent |

| National security | Intellectual |

| Pleasure | Logical |

| Salvation | Loving |

| Self-respect | Obedient |

| Social recognition | Polite |

| True friendship | Responsible |

| Wisdom | Self-controlled |

Source: Milton Rokeach, Value Survey (Sunnydale, CA: Halgren Tests, 1967).

A CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

Comparing Cultural Values

Do the criteria for an ethical speaker outlined in this chapter—that is, displaying the qualities of trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, and fairness—apply equally in every culture? For example, does telling the truth always take precedence over other qualities, such as protecting the interests of your clan or group, or simply being eloquent? Are ethical standards for speeches merely a product of a particular culture? What about the concept of plagiarism? In the United States, speakers who fail to acknowledge their sources meet with harsh criticism and often suffer severe consequences, even if, as in the case of several recent college presidents and professors, the speakers are otherwise highly respected.1 Is this universally true?2 Can you think of examples in which ideas of ethical speech expressed in this chapter are not necessarily shared by other cultures? Do you personally hold values for ethical speech that are different from those cited here?

Charles Taylor/Shutterstock

Use Your Rights of Free Speech Responsibly

Perhaps no other nation in the world has as many built-in safeguards for its citizens’ right to free expression as the United States. The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution plays a pivotal role in enforcing these safeguards by guaranteeing freedom of speech (“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech . . . ”). However, it is often difficult for our state and federal judges (who are charged with interpreting the Constitution) to find a satisfactory balance between our right to express ourselves (our civil liberties) and our right to be protected from speech that harms us (our civil rights). Whose rights should be protected? Should a “shock jock’s” right to spew racist remarks be upheld over the objections of the victims of those remarks?

As today’s judges interpret the Constitution, it would appear that profane radio announcers, along with the rest of us, are largely free to disparage groups and individuals on the basis of their race, gender, weight, or other characteristics. The United States vigorously protects free speech—defined as the right to be free from unreasonable constraints on expression12—even when the targets of that speech claim that it infringes on their civil rights to be protected from discrimination.

Nevertheless, there remain important limits on our right to speak freely, and as a public speaker you should be aware of these limitations. For example, certain types of speech are actually illegal, including the following:

- Speech that provokes people to violence (termed incitement or “fighting words”) and that “by their utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.”13

- Speech that can be proved to be defamatory (termed slander) or potentially harmful to an individual’s reputation at work or in the community.

- Speech that invades a person’s privacy, such as disclosing personal information about an individual that is not in the public record.

The law makes a distinction between whether the issues or individuals you are talking about are public or private. If you are talking about a public figure or a matter of public concern, you have much more latitude to say what you think, and you will not be legally liable unless it can be shown that you spoke with a reckless disregard for the truth. That is, you can be legally liable if it can be shown that you knew that what you were saying was false but said it anyway. If, on the other hand, in your speech you talk about a private person or private matters involving that person, it will be easier for that person to successfully assert a claim for defamation. You will then have the burden of proving that what you said was true.

While a limited range of speech is not legal, speakers who seek to distort the truth about events often can do so, without suffering any consequences. You may express an opinion questioning the existence of the Holocaust or the suffering of African Americans under slavery and not be arrested. The fact that this sort of offensive speech is legal, however, does not necessarily mean that it is ethical. While there are various approaches to evaluating ethical behavior, common to all of them are the fundamental moral precepts of not harming others and telling the truth.

Avoid Hate Speech

Hate speech is any offensive communication—verbal or nonverbal—that is directed against people’s racial, ethnic, religious, gender, or other characteristics. Racist, sexist, or ageist slurs, gay bashing, and cross burnings are all forms of hate speech. Ethically, you are bound to actively avoid any hint of hate speech, ethnocentrism, and stereotyping.

Speakers who exhibit ethnocentrism act as though everyone shares their point of view and points of reference. They may tell jokes that require a certain context or refer only to their own customs. Ethical speakers, by contrast, assume differences and address them respectfully.

Generalizing about an apparent characteristic of a group and applying that generalization to all of its members is another serious affront to people’s dignity. When such racial, ethnic, gender, or other stereotypes roll off the speaker’s tongue, they pack a wallop of indignation and pain for the people to whom they refer. In addition, making in-group and out-group distinctions, with respect shown only to those in the in-group, can make listeners feel excluded or, worse, victimized. Speaking as though all audience members share the same religious and political beliefs, for instance, and treating those beliefs as superior to those held by others, is but one example of making in-group and out-group distinctions. Hate speech is the ultimate vehicle for promoting in-group and out-group distinctions.

ETHICALLY SPEAKING

Speech Codes on Campus: Protection or Censorship?

The existence of speech codes at U.S. colleges and universities has long been at the center of the debate over free speech versus censorship. On the one side are those who resist restrictions of any kind, often in support of the constitutional rights of the First Amendment. On the other side are advocates of speech codes and other policies that limit what students and faculty can and cannot say and do. These advocates argue that speech codes—university regulations prohibiting expressions that would be constitutionally protected in society at large—are necessary to ensure a tolerant and safe environment.

Since the 1980s, thousands of schools, both public and private, have instituted speech codes prohibiting certain forms of offensive speech and acts deemed intimidating or hostile to individuals or groups. Many of these early codes were found to be unconstitutional, but new codes have also come under fire. In 2013, for example, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) found that 62 percent of the nation’s 409 largest and most prestigious colleges and universities maintain policies that “seriously infringe on the free speech rights of students.”1 This figure is actually going down; in 2010 FIRE found that 70 percent of the schools surveyed infringed on constitutionally protected speech. Schools in Illinois and Wisconsin fared worst, restricting protected speech on all campuses. Students in Mississippi and Virginia fared better, where a third of the schools did not enforce speech codes.

Many colleges and universities limit student protests and demonstrations to designated areas on campus called “free speech zones”; these, too, are subject to ongoing legal challenges. Colleges have even tried to collect fees from student groups who sponsor speakers that require campus security. In October of 2009, for example, Dutch politician Geert Wilders spoke about the dangers of Islamic extremism at Temple University. A month later, the student group Temple University Purpose (TUP) received a bill for $800 for charges needed to “secure the room.” The university later dropped the fee when it was shown to be unconstitutional to financially burden students for speech “simply because it might offend a hostile mob.”2

And what about that speech topic you might have in mind? At Central Connecticut State University student John Wahlberg was asked to prepare a speech on a topic covered by the mainstream media. Wahlberg chose to argue that had students at Virginia Tech been allowed to carry concealed weapons on campus during the 2007 shootings at that campus, the shooter might have been killed before killing as many students as he did. Believing that Wahlberg’s opinions made the class “uncomfortable,” his professor reported him to campus police, who ordered him to explain his beliefs.3

Restrictions on speech on campus raise important ethical questions. University administrators who support speech codes claim that they are necessary to protect students from intimidation, to ensure equal opportunity, and to enforce the norms of a civil society.4 Detractors argue that limits on free speech prevent students with unpopular or politically incorrect views from freely expressing themselves. What do you think?

Radu Bercan/Shutterstock