Conduct Smart Searches

Armed with an understanding of the nature of primary and secondary sources, consider how you can search most effectively for the sources you need. Begin at a library portal, access subject guides, use search engines selectively, and identify when to use keywords and subject headings to retrieve the best results.

Access Subject Guides

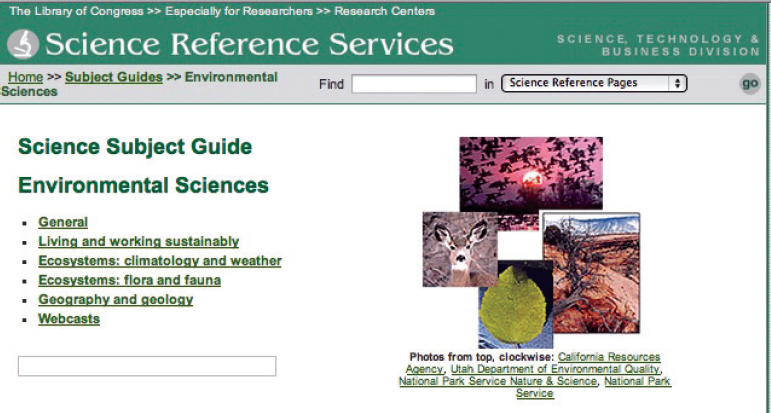

A subject guide (also called a “research guide”) is a collection of article databases, reference works, websites, and other resources for a particular subject. Compiled by librarians, subject guides provide depth and breadth about a topic by providing links to numerous sources devoted to it (see Figure 9.1).

In the example above, the Library of Congress Subject Guide for Environmental Sciences, available online to everyone, provides links to various subjects specific to environmental science, such as Living and Working Sustainably, Ecosystems: Climatology and Weather, and Geography and Geology. The website for the Library of Congress offers a Research and Reference section that provides links to general collections, including business, science, law, literature, history, as well as periodicals.

Use Search Engines Selectively

General search engines (such as Google, Yahoo!, and Duck Duck Go) automatically search Web pages across topics, using software robots to scan billions of documents that contain the keyword and phrases you command them to search. Specialized search engines (also called “vertical search engines”) search only for specific types of Web content, letting you conduct narrower but deeper searches into a particular field. Examples include Google Scholar, which searches scholarly books and articles; www.usa.gov, which allows you to search government sites; and Scirus Science search, a scientific-only, peer-reviewed search engine. To find a search engine geared specifically to your topic, type in the topic term with the keywords search engine. For example, a search for internships and search engine will lead you to various specialized sites, including www.idealist.org and www.internweb.com.

Create Effective Keywords and Subject Headings

You can research a topic by keyword or by subject heading (as well as by other fields, such as author, title, and date); see the help section of the search tools you select for the fields to use. The most effective means of retrieving information with a general search engine is by keyword; for library catalogs and databases, subject searching often yields the best results.

Create Effective Keywords

Keywords are words and phrases that describe the main concepts of topics. Search engines such as Google index information by keywords tagged within documents. Queries using keywords that closely match those tagged in the document will therefore return the most relevant results.

When using a general search engine, follow these tips to create effective keyword queries:

- Use more rather than fewer words. Single-word queries (e.g., cars) will produce too many results; use more (descriptive) words to find what you need (e.g., antique cars OR automobiles). Try to use nouns and objects, and avoid articles (the, a) and pronouns (you, her) as these do not help narrow or target your results.

- Use quotation marks. Quotation marks allow you to find exact phrases (e.g., “white wine”).

- Use Boolean operators. Use words placed between keywords (e.g., AND, OR, NOT) to specify how keywords are related.

- Use nesting. Use parentheses and OR to search for synonymous terms, for example, “graduate school” AND (employment OR jobs) or to retrieve two separate searches simultaneously, for example, “archaeological dig” AND “summer school” (Kenya OR California).

- Use truncation. To retrieve different forms of a word, affix an asterisk to it: Run* (retrieves, e.g., running, ran, runners . . . ). You can also combine a truncated search with another term: Run* AND marathon.

- Consult the search tips section. Every search engine and database has a help or search tips section. Review tips for use before searching.

Identify the Correct Subject Headings

Keyword searches, while most efficient when using general search engines, may yield unsatisfactory results in a library catalog or database. Here the tool of choice is the subject heading—a term selected by information specialists (such as librarians) to describe and group related materials in a library catalog, database, or subject guide (e.g., cookery for cooking-related articles). Identifying the correct heading is the key to an effective subject search. If you use the wrong term in a catalog or database (such as keying in Lou Gehrig’s disease rather than the medical term amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), no results may appear, when in fact a wealth of sources exists, organized under another subject heading.

Librarians agree that searching by subject headings is the most precise way to locate information in library databases. But how to identify the right subject headings? One tactic is to check whether the database includes a thesaurus of subject headings. Another option is to do a keyword search of important terms related to your topic in a general search engine. Then try these in your subject search of your library’s databases.

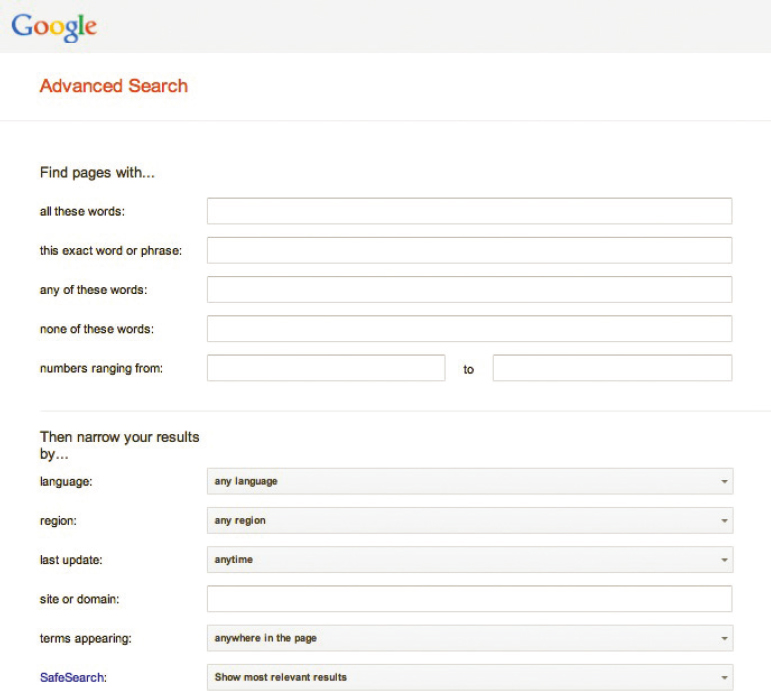

Use Advanced Search

The “Advanced Search” function of many search engines and databases allows you to go beyond basic search commands and narrow results even more (see Figure 9.2). Advanced search includes (at least) the following fields:

- “All,” “exact phrase,” “at least one,” and “without” filter results for keywords in much the same way as basic search commands.

- Language includes search results in the specified language.

- Country searches for results originating in the specified country.

- File format returns results in document formats such as Microsoft Word (.doc), Adobe Acrobat (.pdf), PowerPoint (.ppt), and Excel (.xls).

- Domain limits results to specified Internet domains (e.g., .com, .edu, .gov, .org).

- Date searches focus on a specified range of time.

A CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

Discovering Diversity in Reference Works

In addition to the rich cultural resources to be found in digital collections (see “Access Digital Collections”), a wealth of reference works exists for speakers who seek information on the accomplishments of the many ethnic, cultural, and religious communities that make up the United States. Hundreds of specialized encyclopedias focus on specific ethnic groups and religions. Oxford University Press publishes two volumes of the Encyclopedia of African-American History, while Grolier publishes Encyclopedia Latina. Routledge publishes the Encyclopedia of Modern Jewish Culture. Key in encyclopedia AND [ethnic group] and see what you find.

Among specialized almanacs, multiple publishers produce versions of Asian American almanacs, Muslim almanacs, Native North American almanacs, African American almanacs, and Hispanic American almanacs, along with a host of similar publications. Each reference work contains essays that focus on all major aspects of group life and culture. One way to see what’s available is to search a database such as www.worldcat.org or www.amazon.com, and key in almanac AND ethnic.

Charles Taylor/Shutterstock

Be a Critical Consumer of Information

Anyone can post material on the Web and, with a little bit of design savvy, make it look professional. Discerning the accuracy of online content is not always easy. Search engines such as Google cannot discern the quality of information; only a human editor can do this. Each time you examine a document, especially one that has not been evaluated by credible editors, ask yourself, “Who put this information here, and why did they do so? What are the source’s qualifications? Where is similar information found? When was the information posted, and is it timely? (See “From Source to Speech: Evaluating Web Sources.”)