READING ACTIVELY AND THINKING CRITICALLY

To understand the relationships among the ideas presented in an argument essay, plan to read the argument at least twice — once to get an overview of the issue and the claim and a second time to annotate the argument and jot down your own reactions. (For more on reading strategies, see Chapter 3.)

BEFORE YOU READ

- Think about the title. The title may indicate the issue and claim.

- Check the author’s name and credentials. If you recognize the author’s name, you may have some sense of what to expect in the essay. For example, an essay written by syndicated columnist Dave Barry, who is known for his humorous articles, would likely make a point through humor or sarcasm. In contrast, an essay by former vice president Al Gore would likely take an earnest, serious approach. Also determine whether the author is qualified to write on the topic. (For more on evaluating sources, see Chapter 22.)

Essays in newspapers, magazines, and academic journals often include a brief review of the author’s credentials and experience. Books may include a biographical note about the author. When an article is published without an author’s name, which often happens in newspapers, base your evaluation on the reliability of the publication in which the article appears.

- Look for the original source of publication, and identify its slant and intended audience. If the essay was originally published elsewhere, use the headnote, footnotes, or list of acknowledgments (often at the end of the book) to determine the original source. Some publications have a particular viewpoint. For example, Ms. magazine has a feminist slant, and its intended audience is educated, professional women. Wired generally favors advances in technology.

- Check the publication date. The more recent an article is, the more likely it is to reflect current research or debate. For instance, an essay speculating on the existence of life on other planets written in the 1980s would lack recent scientific findings that might confirm or discredit the supporting evidence. Hint: When obtaining information from the Internet, be especially careful to check the date the article was posted or last updated.

- Preview the essay. Read the opening paragraph, headings, the first sentence of one or two paragraphs per page, and the last paragraph. Previewing may help you determine the author’s claim.

- Think about the issue before you read. When you think about the subject of the argument before reading, you may be less influenced by the writer’s appeals and more likely to maintain an objective, critical viewpoint. Write the issue at the top of page, and then list in two or more columns as many reasons as you can come up with for supporting the main positions on the issue.

WHILE YOU READ

- Read first for an initial impression. Identify the issue and the author’s claim. Try to get a general feel for the essay, the author, and the author’s approach to the topic. Hold off on judging or criticizing the author’s take on the issue until you have analyzed it closely.

- Read a second time with a pen in hand. Mark or highlight the claim, reasons, and key supporting evidence. Note appeals to needs and values, and summarize reasons and key supporting evidence as you encounter them. Understand how the writer defines key terms and concepts. If the author does not define terms precisely, look up their meanings in a dictionary, and jot down the definitions in the margins. Also jot down ideas, questions, or challenges to the writer’s argument.

- Check your comprehension by summarizing or drawing a graphic organizer. Use the following guidelines.

- Review your annotations, noting the function of each section. Be sure you have identified the issue, the claim, sections offering reasons and evidence, opposing viewpoints, and the conclusion. (If you had trouble identifying the parts, reread the essay.) In the left-hand margin, identify the function of each section. You might write “offers examples” or “provides statistical backup,” for instance.

- Write brief notes stating the main point of each paragraph or each related group of paragraphs. Summarize the essay’s main ideas in the right-hand margin. Be sure to use your own words, not the author’s.

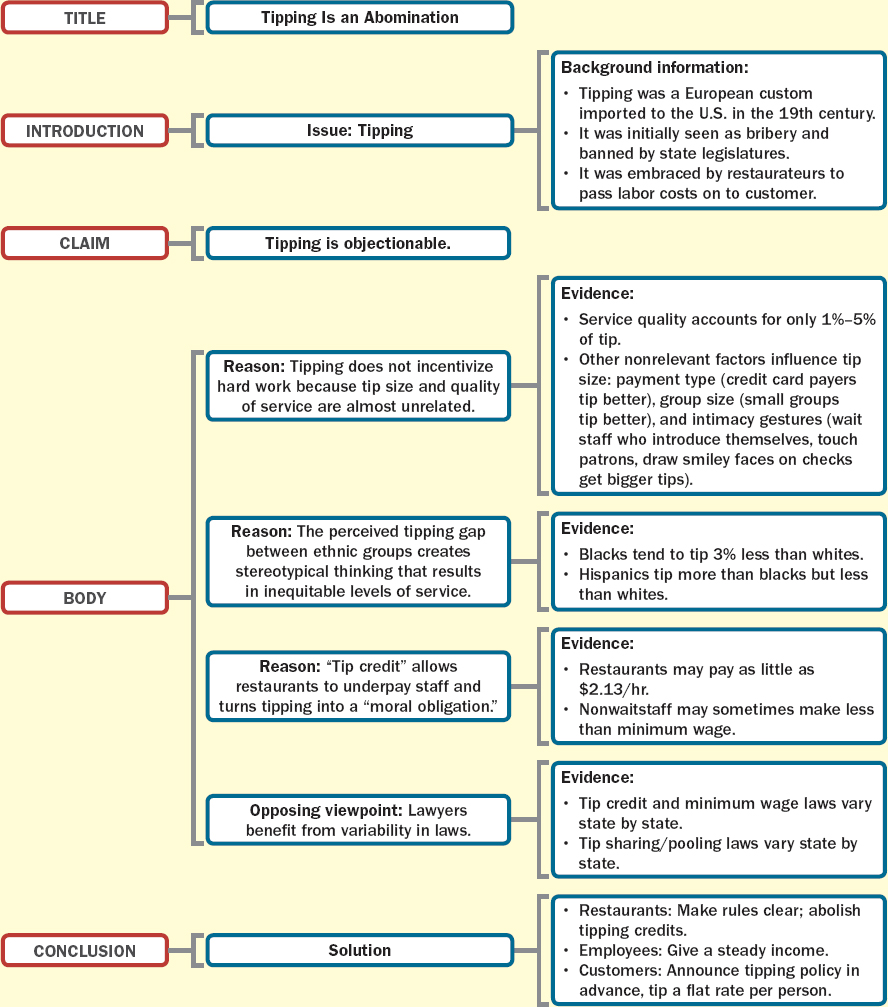

- Develop a summary from your notes or complete a graphic organizer. Verbal and abstract learners may prefer to create a summary; concrete and spatial learners may prefer to create a graphic organizer. Social learners may prefer to work with a classmate. The following sample summary of “Tipping Is an Abomination” shows an acceptable level of detail; a graphic organizer for this selection appears in Figure 20.2.

SAMPLE SUMMARY

When the practice of tipping was introduced in the United States in the late nineteenth century, it was rejected by both state legislatures and American citizens, who considered it a form of bribery. Despite opposition, the custom made its way into American society with the help of restaurateurs, who wanted to shift labor costs to their customers. In “Tipping Is an Abomination,” Brian Palmer argues that the custom is objectionable and of little benefit to anyone except lawyers for three main reasons: because it does not motivate workers to work harder or more efficiently, because the perceived tipping gap between ethnic groups creates stereotypical thinking that results in unequal levels of service, and because differences in state laws regarding the tipping credit and tip sharing leads to costly lawsuits for restaurants. To solve the problem, Palmer concludes by suggesting that states abolish the tipping credit for restaurants, which would make the rules clear for restaurants and give employees a steady income. He also suggests that customers make their tipping practice known before receiving service and that they tip a flat rate per person, despite the size of the group.

ANALYZING THE BASIC COMPONENTS OF AN ARGUMENT

As you read an argument, consider the following aspects of all persuasive writing. (For more on evaluating evidence, see Chapter 6.)

- The writer’s purpose. Ask yourself: Why does the writer want to convince me of this? What does he or she stand to gain, if anything? Be particularly skeptical if a writer stands to profit personally from your acceptance of an argument.

- The intended audience. Use the tone and the formality or informality of the language to figure out the type of audience — receptive, hostile, interested but skeptical — the author is expecting to address. How receptive the intended audience is expected to be might help you understand and evaluate the writer’s argument. For example, writers addressing a receptive audience may not argue as carefully for their claims as would writers addressing a skeptical or hostile audience.

- The writer’s credibility. Consider the writer’s knowledge and trustworthiness. Ask yourself whether the writer has a thorough understanding of the issue, acknowledges opposing views and represents them fairly, and establishes common ground with readers by acknowledging their needs and values.

- Support: reasons and evidence. To assess the reasons and evidence, ask yourself questions like these: Does the writer offer enough reasons, do those reasons make sense, and are they relevant? Does the author supply enough evidence, and is that evidence accurate, complete, representative, up-to-date, and taken from reputable sources? Are the authorities cited experts in their field? Are sources cited formally or informally? (For more on evaluating evidence, see Chapter 6.)

- Definitions of key terms. Underline any terms that can have more than one meaning. Then read through the essay to see if the author defines these terms clearly and uses them consistently. Pay particular attention to words that appeal to values, because not everyone considers the same principles or qualities important or agrees on the definition of a value.

IDENTIFYING EMOTIONAL APPEALS

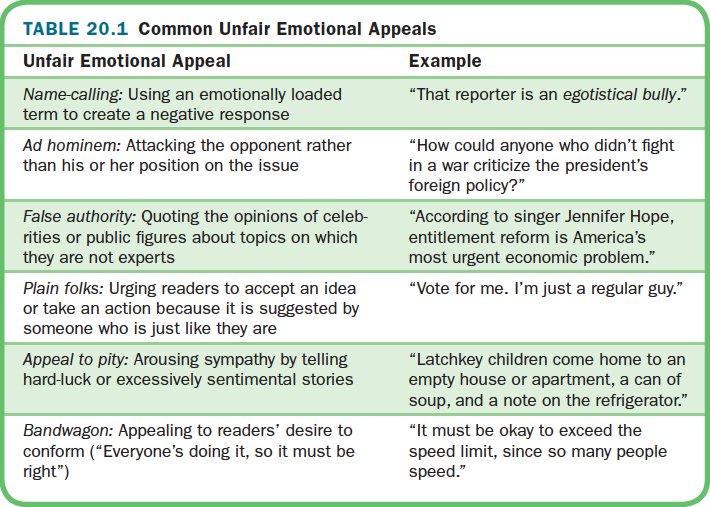

Emotional appeals are a legitimate part of an argument. However, writers should not attempt to manipulate readers’ emotions to distract them from the issue and the evidence.Table 20.1 presents some common unfair emotional appeals.

EVALUATING OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

If an argument essay takes into account opposing viewpoints, you must evaluate how the writer presents them. Ask yourself the following questions.

- Does the author state the opposing viewpoint clearly?

- Does the author present the opposing viewpoint fairly and completely? That is, does the author treat the opposing viewpoint with respect or attempt to discredit or demean those holding the opposing view? Does the author present all the major parts of the opposing viewpoint or only those parts that he or she is able to refute?

- Does the author clearly show why he or she considers the opposing viewpoint wrong or inappropriate? Does the author apply sound logic? Does the author provide reasons and evidence?

- Does the author acknowledge or accommodate points that cannot be refuted?

DETECTING FAULTY REASONING

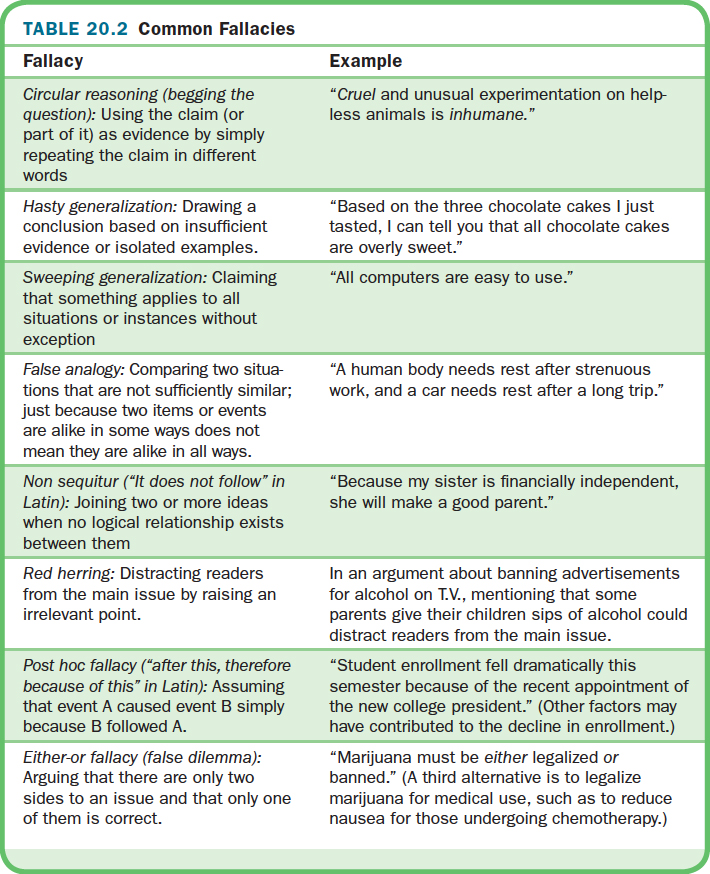

In some arguments, a writer may commit fallacies, errors in reasoning or thinking. Fallacies can weaken an argument, undermine a writer’s claim, and call into question the relevancy, believability, or consistency of supporting evidence. Table 20.2 provides a brief review of the most common types of faulty reasoning. (For more on reasoning, see Chapter 21.)