CHARACTERISTICS OF ARGUMENT ESSAYS

In developing an argument essay, you need to select a controversial issue, make a clear and specific claim that takes a position on the issue, and give reasons and evidence to support the claim that will appeal to your audience. In addition, you should follow a logical line of reasoning; use emotional appeals appropriately; and acknowledge, accommodate, or refute opposing views.

ARGUMENTS FOCUS ON ARGUABLE, NARROWLY DEFINED ISSUES

An issue is a controversy, problem, or idea about which people disagree. When writing an argument, be sure your issue is controversial. For example, free public education is an important topic, but it is not particularly controversial. (Most people would be in favor of at least some forms of free public education.) Instead, you might choose the issue free public college education or universal, free prekindergarten education.

Depending on the issue you choose and the audience you write for, a clear definition of the issue may be required. In addition, your readers may need background information. For example, in an argument about awarding organ transplants, you may need to give general readers information about the scarcity of organ donors versus the number of people who need transplants.

The issue you choose should be narrow enough to deal with adequately in an essay-length argument. For a brief (three- to five-page) essay on organ transplants, for instance, you could narrow your focus to transplants of a particular organ or to one aspect of the issue, such as who should and should not receive them. A narrow focus will allow you to offer more detailed reasons and evidence and respond to opposing viewpoints more effectively.

AN ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS MAKES A SPECIFIC CLAIM AND MAY CALL FOR ACTION

To build a convincing argument, you need to make a clear and specific claim, one that states your position on the issue clearly. To keep your essay on track, state your claim in a strong thesis in the introduction or early in the essay. As you gain experience in writing arguments, you can experiment with placing your thesis later in the essay.

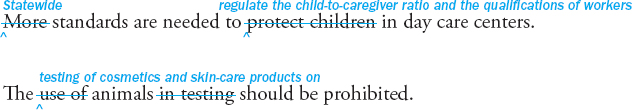

Here are a few examples of how general claims can be narrowed to create clear and specific thesis statements. (For more on types of claims, see Chapter 20.)

While all arguments make and support a claim, some, like claims of policy, also call for a specific action to be taken. An essay opposing human cloning might urge readers to voice their opposition in letters to congressional representatives, for example.

Be careful about the way you state your claim. In most cases, avoid an absolute statement that applies to all cases; your claim will be more convincing if you qualify, or limit, it by using words and phrases like probably, often, and for the most part. For example, the claim, “Single-sex educational institutions are always more beneficial to girls than coeducational schools are,” could easily be undermined by a critic by citing a single exception. If you qualify your claim — “Single-sex educational institutions are often more beneficial to girls than are coeducational schools” — then an exception would not necessarily weaken the argument.

EFFECTIVE ARGUMENTS ARE LOGICAL

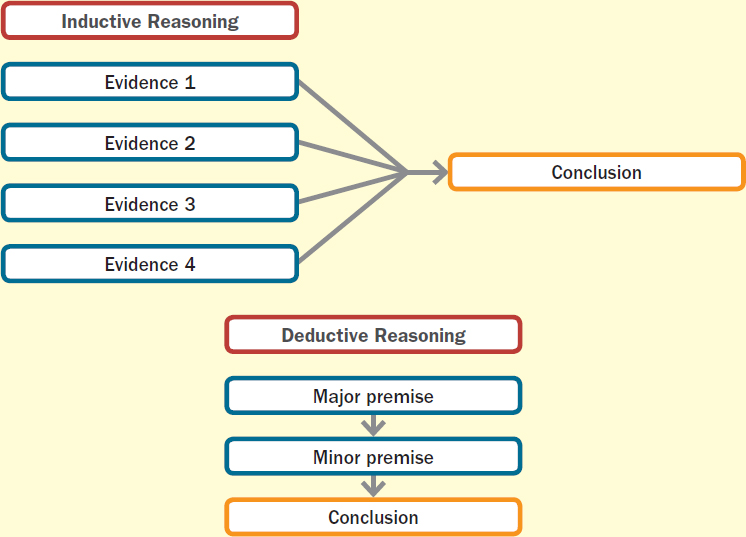

The reasons and evidence in an argument should follow a logical line of reasoning. The most common types of reasoning are induction and deduction (see Figure 21.1). Inductive reasoning begins with evidence and moves to a conclusion; deductive reasoning begins with a commonly accepted statement, or premise, and shows how a conclusion follows from it. You can use one or both types of reasoning to keep your argument on a logical path.

Inductive reasoning. Think of inductive reasoning as a process of coming to a conclusion after observing a number of examples. For example, suppose you go shopping for a new pair of sneakers. You try on one style of Nikes. The sneakers don’t fit, so you try a different style. That style doesn’t fit either. You try two more styles, neither of which fits. Finally, because of your experience, you draw the conclusion that either you need to remeasure your feet or Nike does not make a sneaker that fits your feet.

When you use inductive reasoning, you make an inference, or guess, about the cases that you have not experienced. In doing so, you run the risk of being wrong. When building an inductive argument, be aware of some potential pitfalls:

- Consider as many possible explanations for the cases you observe as you can. In the sneaker example, perhaps the salesperson brought you the wrong size.

- Be sure that you have sufficient and typical evidence on which to base your conclusion. Suppose you learn that one professional athlete was involved in a driving-while-intoxicated incident and that another left the scene of an auto accident. If, from these limited observations, you conclude that professional athletes are irresponsible, your reasoning is faulty because these two cases are not typical of all professional athletes and not sufficient for drawing a conclusion. (If you draw a conclusion based on insufficient evidence or isolated examples, you have committed the fallacy of hasty generalization. You may also have committed a sweeping generalization — drawing a conclusion that applies to all cases without exception. (For more on common fallacies, see Table 20.2.)

When you use inductive reasoning in an argument essay, the conclusion becomes the claim, and the specific pieces of evidence support your reasons for making the claim. For example, suppose you make a claim that Pat’s Used Cars is an unethical business from which you should not buy a car. As support you might offer the following reasons and evidence.

| REASON | Pat’s Used Cars does not provide accurate information about its products. |

| EVIDENCE | My sister’s car had its odometer reading tampered with. My best friend bought a car whose chassis had been damaged, yet the salesperson claimed the car had never been in an accident. |

| REASON | Pat’s Used Cars doesn’t honor its commitments to customers. |

| EVIDENCE | The dealership refused to honor the ninety-day guarantee for a car I purchased there. A local newspaper recently featured Pat’s in a report on businesses that fail to honor guarantees. |

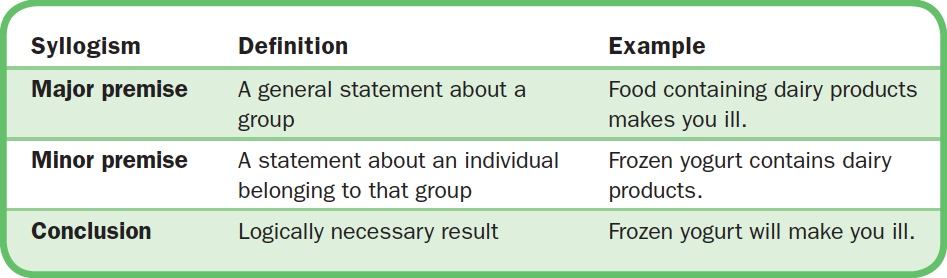

Deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning begins with premises — statements that are generally accepted as true. Once the premises are accepted as true, the conclusion must also be true. The most common deductive argument is a syllogism, which consists of two premises and a conclusion.

When you use deductive reasoning, putting your argument in the form of a syllogism will help you write your claim, then organize and evaluate your reasons and evidence. Suppose you want to support the claim that state funding for Kids First, an early childhood program, should remain intact. You might use the following syllogism to build your argument.

| MAJOR PREMISE | State-funded early childhood programs have increased the readiness of at-risk children to attend school. |

| MINOR PREMISE | Kids First is a popular early childhood program in our state, where it has had many positive effects. |

| CONCLUSION | Kids First is likely to increase the readiness of at-risk children to attend school. |

Your thesis statement would be, “Because early childhood programs are likely to increase the readiness of at-risk children to attend school, state funding for Kids First should be continued.” Your evidence would be information demonstrating the effectiveness of Kids First, such as the school performance of at-risk students who attended Kids First versus the school performance of at-risk students who did not and the cost of remedial education in later years versus the cost of Kids First.

EFFECTIVE ARGUMENTS DEPEND ON CAREFUL AUDIENCE ANALYSIS

To build a convincing argument, you need to know your audience. Analyze your audience to determine their education, background, and experience. Then also consider the following.

- How familiar your audience is with the issue

- Whether your audience is likely to agree, be neutral or wavering, or disagree with your claim

This knowledge will help you select reasons and evidence and choose appeals that your readers will find compelling. (For more on audience analysis, see Chapter 5.)

Agreeing audiences. Agreeing audiences are the easiest to write for because they already accept your claim. When you write for an audience that is likely to agree with your claim, the focus is usually on urging readers to take a specific action. Instead of having to offer large amounts of facts and statistics as evidence, you can concentrate on reinforcing your shared viewpoint and building emotional ties with your audience. By doing so, you encourage readers to act on their beliefs.

Neutral or wavering audiences. Although they may be somewhat familiar with the issue, neutral or wavering audiences may have questions about, misunderstandings about, or no interest in the issue. When writing for this type of audience, emphasize the importance of the issue or shared values, and clear up misunderstandings readers may have. Your goals are to make readers care about the issue, establish yourself as a knowledgeable and trustworthy writer, and present solid evidence in support of your claim.

Disagreeing audiences. The most challenging audience is one that holds viewpoints in opposition to yours. The people in such an audience may have strong feelings about the issue and may distrust you because you don’t share their views. In writing for a disagreeing audience, your goal is not necessarily to persuade readers to adopt your position but rather to convince them to consider your views. To be persuasive, you must follow a logical line of reasoning. Rather than stating your claim early in the essay, it may be more effective to build slowly to your thesis, first establishing common ground, a basis of trust and goodwill, by mentioning shared values, interests, concerns, and experiences.

EFFECTIVE ARGUMENTS PRESENT REASONS AND EVIDENCE READERS WILL FIND COMPELLING

In developing an argument, you need to provide reasons for making a claim. A reason is a general statement that backs up a claim; it answers the question, “Why do I have this opinion about this issue?” You also need to support each reason with evidence.

Suppose you want to argue that high school uniforms should be mandatory. You might give three reasons.

- Uniforms reduce clothing costs for parents.

- They help eliminate distractions in the classroom.

- They reduce peer pressure.

You would need to support each of your reasons with some combination of evidence, facts, statistics, examples, personal experience, or expert testimony. Carefully linking your evidence to reasons helps your readers see how the evidence supports your claim.

Choose reasons and evidence that will appeal to your audience. In the argument about mandatory school uniforms, high school students would probably not be impressed by your first reason, but they might be persuaded by your second and third reasons if you cite evidence that appeals to them, such as personal anecdotes from other students. For an audience of parents, facts and statistics about reduced clothing costs and improved academic performance would be appealing types of evidence.

EFFECTIVE ARGUMENTS APPEAL TO READERS’ NEEDS AND VALUES

Although an effective argument relies mainly on credible evidence and logical reasoning, emotional appeals to readers’ needs and values can help support and strengthen a sound argument. Needs can be biological or psychological (food and drink, sex, a sense of belonging, self-esteem). Values are principles or qualities that readers consider important, worthwhile, or desirable. Examples include honesty, loyalty, privacy, and patriotism. (For more on emotional appeals, see Chapter 20.)

EFFECTIVE ARGUMENTS RECOGNIZE ALTERNATIVE VIEWS

Recognizing and countering alternative perspectives on an issue forces you to think hard about your claims. When you anticipate readers’ objections, you may find reasons to adjust your reasoning and develop a stronger argument. Readers will also be more willing to consider your claim if you take their point of view into account.

You can recognize alternative views in an argument essay by acknowledging, accommodating, or refuting them.

- Acknowledge an alternative viewpoint by admitting that it exists and showing that you have considered it.

EXAMPLE Readers opposed to mandatory high school uniforms may argue that a uniform requirement will not eliminate peer pressure because students will use other objects to gain status, such as backpacks, iPads, and smartphones. You could acknowledge this viewpoint by admitting that there is no way to stop teenagers from finding ways to compete for status. - Accommodate an alternative viewpoint by acknowledging readers’ concerns, accepting some of them, and incorporating them into your argument.

EXAMPLE In arguing for mandatory high school uniforms, you might accommodate readers’ view that uniforms will not eliminate peer pressure by arguing only that uniforms will eliminate one major and expensive means of competing for status. - Refute an opposing viewpoint by demonstrating the weakness of the opponent’s argument.

EXAMPLE To refute the viewpoint that uniforms force students to give up their personal style, you can argue that the majority of students’ lives are spent outside school, where uniforms are not necessary and where each student is free to express his or her individuality.

The following readings demonstrate the techniques for writing effective argument essays discussed above. The first reading is annotated to point out how Amitai Etzioni and Radhika Bhat make an arguable claim, provide reasons and evidence in support of their claim, and respond to alternative views. As you read the second essay, pay particular attention to the logic of the argument and the strategies William Safire uses to appeal to his audience.