WORKING WITH SOURCES: TAKING NOTES, SUMMARIZING, AND PARAPHRASING

Reading sources involves some special skills. (For more on previewing, see Chapter 3.) Unlike textbook reading, in which your purpose is to learn and recall the material, you usually read sources to extract the information you need about a topic. Therefore, you can often read sources selectively, previewing the source to identify relevant sections and reading just those sections.

TAKING NOTES

Your purpose in conducting research is to explore your topic, consider multiple perspectives, and gradually arrive at your own main point — your thesis. As you conduct research, your ideas will develop, and you will generate topic sentences based on a synthesis of sources that you’ve read. In fact, the development of these integrated or synthesized ideas is a key goal of writing a research project. (For more on creating entries in a works-cited list, see "Documenting Your Sources: MLA Style"; for more on creating entries in a references list, see "Documenting Your Sources: APA Style.)

Because you must give credit to those who informed your thinking, record all the source information that you will need when creating your list of works cited. Be particularly cautious when cutting and pasting source materials into your notes. Always place quotation marks around anything you have cut and pasted. Be sure to clearly separate your ideas from the ideas you found in sources. If you copy an author’s exact words, place the information in quotation marks, and write the term direct quotation as well as the page number(s) in parentheses after the quotation. If you write a summary note or paraphrase, write paraphrase or summary and the page number(s) of the source. Be sure to include page numbers; you’ll need them to double-check your notes against the source and to create a works-cited entry.

Note-taking tools. Many students use a series of computer folders or a notebook for their research. In a notebook, you might use section dividers for different components of your research; in a computer folder, you might use various subfolders. A notebook or computer file is a good place to store copies of research materials that you have copied or downloaded.

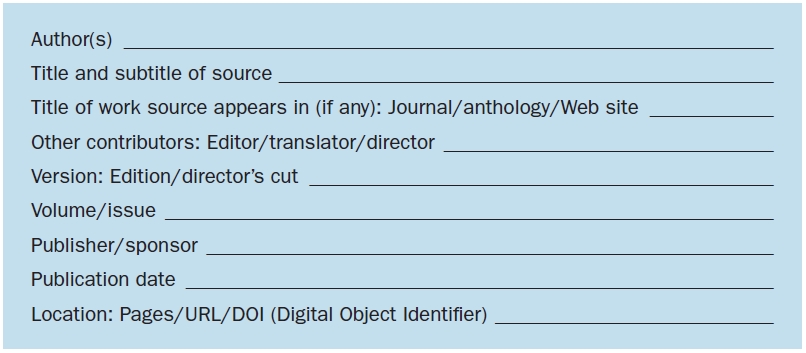

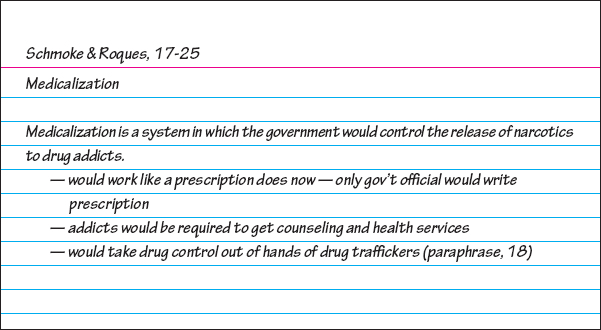

While many students prefer to take notes in computer files or notebooks, some researchers still like to use index cards for note-taking. (There are also programs available that allow you to create computerized note cards.) Note cards allow you to arrange and rearrange the material to experiment with different ways of organizing your project. If you decide to use note cards, put information from only one source or about only one subtopic on each card. At the top of the card, indicate the author of the source and the page numbers on which the information appears, and note the subtopic that the note covers. (Figure 23.6.)

Citation (or reference) managers, programs like Mendeley, RefWorks, and Zotero, can be useful tools throughout the research process because they allow you to save sources, take notes, and incorporate those notes into your research project as you write. They may also help you format your works cited or reference list entries.

Annotating and highlighting source materials. Annotating and highlighting (or underlining) can be a useful system of engaging closely with source materials. You may annotate and highlight using a pencil and a highlighting marker or using the annotation and highlighting features available with some electronic documents. You can then store these annotated documents in a notebook pocket, a computer file, or a citation manager. Remember to be selective about what you mark or comment on as you annotate, keeping the purpose of your research in mind. (For more on annotating and highlighting, see Chapter 3.)

TAKING NOTES THAT SUMMARIZE, PARAPHRASE, OR QUOTE

Much of your note-taking should summarize, or condense, information from sources, since you will mostly not need the exact wording or the kinds of details you would include in a paraphrase.

After summarizing, paraphrasing is probably the second-most common form your notes should take. Paraphrase when recording the supporting details is important, but paraphrase only the ideas or details you intend to use. Both summarizing and paraphrasing force you to understand the source.

Including direct quotations — writers’ exact words — is probably the least common form your notes should take, but including quotations in your notes can still be advisable, even necessary. Use quotations to record wording that is unusual or striking, capture technical details you might get wrong, or report the exact words of an expert on your topic.

SUMMARIZING

As you write summary notes, keep the following in mind.

- Everything you put in summary notes must be in your own words and sentences.

- Your summary notes should accurately reflect the relevant main points of the source. (For more on writing summaries, see Chapter 3.)

Use the guidelines below to write effective summary notes.

- Record only information that relates to your topic and purpose.

- Write notes that condense the author’s ideas into your own words. Include key terms and concepts or principles, but omit specific examples, quotations, or anything else that is not essential to the main point and your own opinion. You can write comments in a separate note.

- Record the ideas in the order in which they appear in the original source. Reordering ideas might affect the meaning.

- Reread your summary to determine whether it contains enough information. Consider whether it would it be understandable to someone who has not read the original source.

- Record the complete publication information for the sources you summarize. Unless you summarize an entire book or poem, you will need to include page references when you write your paper and prepare a works-cited list.

A sample summary of the first four paragraphs of the essay “Dude, Do You Know What You Just Said?” appears below. Read or reread paragraphs 1–4, and then study the summary.

SAMPLE SUMMARY

“Dude, Do You Know What You Just Said?” reports on the findings of Scott Kiesling, a linguist who has studied the uses and meanings of the popularly used word dude. Historically, dude was first used to refer to a dandy and then became a slang term used by various social groups. For his study, Kiesling listened to tapes of fraternity members and asked undergraduate students to record uses of the term. He determined that it is used for a variety of purposes, including to show enthusiasm or excitement, one-up someone, avoid confrontation, and demonstrate agreement.

PARAPHRASING

When you paraphrase, you restate the author’s ideas in your own words and sentences. (For more on avoiding plagiarism, see Chapter 24.) You do not condense ideas or eliminate details as you do in a summary; instead, you keep the author’s intended meaning but express that meaning in different sentence patterns and vocabulary. In most cases, a paraphrase is approximately the same length as the original material.

When paraphrasing, be careful not to plagiarize — that is, do not use an author’s words or sentences as if they were your own. Merely replacing some words with synonyms is not enough; you must also use your own sentence structures and may want to reorganize the presentation of ideas. Reading the excerpt from a source below and comparing it, first, with the acceptable paraphrase that follows and then with the example that includes plagiarism will help you see what an acceptable paraphrase looks like.

EXCERPT FROM ORIGINAL

Learning some items may interfere with retrieving others, especially when the items are similar. If someone gives you a phone number to remember, you may be able to recall it later. But if two more people give you their numbers, each successive number will be more difficult to recall. Such proactive interference occurs when something you learned earlier disrupts recall of something you experienced later. As you collect more and more information, your mental attic never fills, but it certainly gets cluttered.

David G. Myers, Psychology

ACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE

According to David Myers, when proactive interference happens, things you have already learned prevent you from remembering things you learn later. In other words, details you learn first may make it harder to recall closely related details you learn subsequently. You can think of your memory as an attic. You can always add more junk to it. However, it will become messy and disorganized. For example, you can remember one new phone number, but if you have two or more new numbers to remember, the task becomes harder.

UNACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE — INCLUDES PLAGIARISM

Replaces terms with synonyms

Copied terms and phrases

When you learn some things, it may interfere with your ability to remember others. This happens when the things are similar. Suppose a person gives you a phone number to remember. You probably will be able to remember it later. Now, suppose two persons give you their numbers. Each successive number will be harder to remember. Proactive interference happens when something you already learned prevents you from recalling something you experience later. As you learn more and more information, your mental attic never gets full, but it will get cluttered.

The unacceptable paraphrase does substitute some synonyms — remember for retrieving, for example — but it is still an example of plagiarism. Not only are some words copied directly from the original, but also the structure of the sentences is nearly identical to the original.

Paraphrasing can be tricky, because letting an author’s language creep in is easy. These guidelines will help you paraphrase without plagiarizing.

- Read first; then write. Read material more than once before you try paraphrasing. To avoid copying an author’s words, cover up the passage you are paraphrasing (or switch to a new window on your computer), and then write.

- Use synonyms that do not change the author’s meaning or intent, and if you must use distinctive wording of the author’s, enclose it in quotation marks. Consult a dictionary or thesaurus if necessary. Note that for some specialized terms and even for some commonplace ones, substitutes may not be easy to come by. In the acceptable paraphrase above, the writer uses the key term proactive interference, as well as the everyday word attic, without quotation marks. However, if the writer paraphrasing the original were to borrow a distinctive turn of phrase, this would need to be in quotation marks. Of course, deciding when quotation marks are or are not needed requires judgment, and if you are not sure, using quotation marks is never wrong.

- Use your own sentence structure. Using an author’s sentence structure can be considered plagiarism. If the original uses lengthy sentences, for example, your paraphrase may use shorter sentences. If the original phrases something in a compound sentence, try recasting the information in a complex one. (For more on varying sentence structure, see Chapter 10.)

- Rearrange the ideas if possible. If you can do so without changing the sense of the passage, rearrange the ideas. In addition to using your own words and sentences, rearranging the ideas can make the paraphrase more your own. Notice that in the acceptable paraphrase above, the writer starts by introducing the term proactive interference, whereas in the original source, this term is not used until the fourth sentence.

Be sure to record the publication information (including page numbers) for the sources you paraphrase. You will need this information to document the sources in your paper.

ORIGINAL SOURCE

Everyone knows that advertising lies. That has been an article of faith since the Middle Ages — and a legal doctrine, too. Sixteenth-century English courts began the Age of Caveat Emptor by ruling that commercial claims — fraudulent or not — should be sorted out by the buyer, not the legal system. (“If he be tame and have ben rydden upon, then caveat emptor.”) In a 1615 case, a certain Baily agreed to transport Merrell’s load of wood, which Merrell claimed weighed 800 pounds. When Baily’s two horses collapsed and died, he discovered that Merrell’s wood actually weighed 2,000 pounds. The court ruled the problem was Baily’s for not checking the weight himself; Merrell bore no blame.

Cynthia Crossen, Tainted Truth

PARAPHRASE

It is a well-known fact that advertising lies. This has been known ever since the Middle Ages. It is an article of faith as well as a legal doctrine. English courts in the sixteenth century started the Age of Caveat Emptor by finding that claims by businesses, whether legitimate or not, were the responsibility of the consumer, not the courts. For example, there was a case in which one person (Baily) used his horses to haul wood for a person named Merrell. Merrell told Baily that the wood weighed 800 pounds, but it actually weighed 2,000 pounds. Baily discovered this after his horses died. The court did not hold Merrell responsible; it stated that Baily should have weighed the wood himself instead of accepting Merrell’s word.

RECORDING QUOTATIONS

Enclose quotations within quotation marks. When writing your paper, you may adjust a quotation to fit your sentence, so long as you do not change the meaning of the quotation, but when taking notes, be sure to record the quotation precisely as it appears in the source. Also provide the page number(s) on which the material being quoted appears in the original source. In your notes, be sure to indicate that you are copying a direct quotation by including quotation marks, the term direct quotation, and the page number(s) in parentheses. (For more on how to adjust a quotation to fit your sentence, see Chapter 24.)

KEEPING TRACK OF SOURCES

In addition to gathering information from sources, you must carefully record the information you will need to cite each source. Using a form like the one shown in Figure 23.6 can help you make sure you record all the information you will need. Using a citation manager can also help. (For more on citing sources, see Chapter 24.) Note that including the call number will be helpful, but you will not need to include this information in your citation.