|

|

Read and analyze your writing assignment carefully. Ask yourself these questions.

- What is my purpose for writing? To explain one element of the work? To argue for my interpretation?

- What are my Instructor’s expectations? What will he or she be looking for?

- Given my and my instructor’s goals for the assignment, how much should I assume that my readers already know about the author, genre, or literary work?

- Am I allowed to do research to find out what others have said about the work or to find background information about the author?

- How will I use additional patterns of development within my literary analysis? For example, you will likely use illustration to cite examples to support your analysis. In addition, you might compare or contrast two main characters or analyze a plot by discussing causes and effects.

|

Explore the work of literature and generate ideas. Try one or more of the following suggestions to devise a focus and generate ideas.

- Highlight and annotate the work. Focus on striking details, such as figures of speech, symbolic images, actions and reactions of characters, repetition, and so on. (All, especially verbal and independent learners, can benefit from highlighting and annotating.)

- Freewrite. Explore your reaction to the work or use a word or image from the work as a jumping off point. (Creative, emotional, and verbal learners will benefit especially from freewriting.)

- Discuss the literary work with classmates. Move from general meaning to a more specific paragraph-by-paragraph or line-by-line examination. Then discuss your interpretation of the work’s theme. (Social and emotional learners will especially benefit from discussing the work with classmates.)

- Write a summary. Doing so may lead you to raise and answer questions about the work. (Rational and pragmatic learners will benefit especially from summarizing.)

- Draw a time line or a character map. For stories with plots that flash back or forward in time, a time line can help you envision the sequence of events. A character map can help you understand characters’ relationships. (Rational, pragmatic, and spatial learners will benefit especially from creating a time line or character map.)

|

Conduct background research. If your instructor allows it, you may develop an interesting focus by putting the work into context.

- Read about the author’s background. Look for connections between the work and the author’s life. For example, writing an interpretation of Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol” might be easier if you understand the author’s own impoverished childhood.

- Explore the historical context. Research the historical, social, economic, and political context of the work. Understanding conditions of the poor in nineteenth-century England might help you understand Dickens’s portrayal of the Cratchit family.

- Discover parallel works or situations. Compare the work to a film or television show or to your own experience to develop insight. For example, comparing your own experience of school English with that of the narrator in “How I Discovered Poetry” may enhance your understanding.

- Apply theories you have learned about in other classes. Theories from your child psychology class may help you understand the sense of loss the narrator experiences in “The Secret Lion.”

|

Evaluate your ideas and choose an approach to your literary analysis. Here are several possible approaches you might choose to take in a literary analysis.

- Evaluate symbolism. Discuss how the author’s use of images and symbols creates a particular mood and contributes to the overall meaning of the work.

- Analyze conflicts. Focus on their causes, effects, or both.

- Evaluate characterization and interpret relationships. Discuss how characters are presented or whether their actions are realistic or predictable. Analyze how their true nature is revealed or how they change in response to circumstances.

- Explore themes. Discover an important point or theme the work conveys, and back up your ideas with examples from the work.

|

|

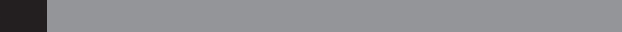

Draft your thesis statement.

- include the author’s name and the work’s title,

- indicate the element of the work you will analyze (its theme, characters, or use of symbols, for example), and

- state the main point you will make about that element.

Notice how the writers include all three elements in these two example thesis statements: Working Together. In groups of two or three students, take turns presenting your thesis statements and main supporting evidence. As group members listen, have them note the element you will analyze and your main point. They should be able to restate your main point in their own words; if they can’t, your main point may not be clear. Brainstorm as a group to:

- clarify your thesis,

- add the missing element, or

- identify evidence or insights the writer may have overlooked.

|

Choose a method of organization.

- Least-to-most works well in literary analyses that highlight one or more important reasons or causes.

- Chronological order works well when exploring events as they occur in the work of literature or when exploring the process by which an author makes events or connections clear.

- Point-by-point or subject-by-subject order works well when comparing or contrasting characters or works of literature.

|

Draft your literary analysis. Use the following guidelines to keep your essay on track.

- The introduction should name the author and title, present your thesis, and suggest why your analysis is useful or important. Try to engage readers’ interest by including a meaningful quotation or a comment on the universality of a character or theme, for example.

- Each body paragraph should include a topic sentence that states your main point, a point that supports your thesis, and enough evidence to support your main point. Include quotations or paraphrases from the work of literature as support, identified by page numbers (for a short story) or line numbers (for a poem). Include a works-cited entry at the end of your paper indicating the edition of the work you used. Use plot summary only where necessary to make the analysis clear. Write in the “literary present” tense (see step 9 below), except when discussing events that occur before the story or poem begins.

- The conclusion should reaffirm your thesis and give the essay a sense of closure. You may want to tie your conclusion to your introduction or offer a final word on your main point.

|

|

Evaluate your draft, and revise as necessary. Use Figure 25.4, “Flowchart for Revising a Literary Analysis Essay” (pp. 684–85), to help you discover the strengths and weaknesses of your draft. You might also ask a classmate to review your draft using the questions in the flowchart. |

|

Edit and proofread your essay.

- editing sentences to avoid wordiness, make your verb choices strong and active, and make your sentences clear, varied, and parallel, and

- editing words for tone and diction, connotation, and concrete and specific language.

Pay particular attention to the following:

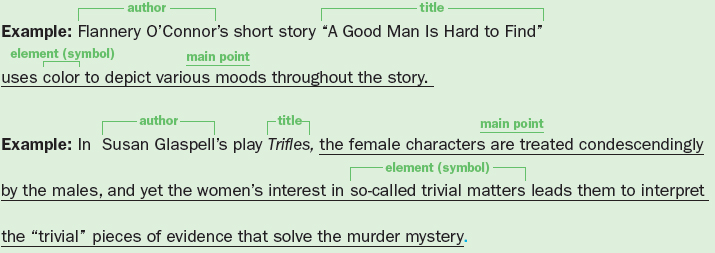

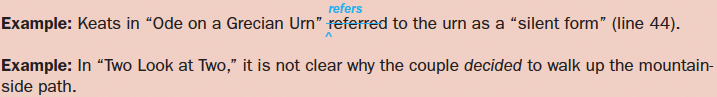

- Use the literary present tense. Even though the poem or short story was written in the past, as a general rule write about the events in it and the author’s writing of it as if they were happening in the present. An exception to this rule occurs when you are referring to a time earlier than that in which the narrator speaks, in which case a switch to the past tense is appropriate.

The couple made the decision before the action in the poem began.

- Punctuate quotations correctly. Direct quotations from a literary work, whether spoken or written, must be placed in quotation marks. Omitted material should be marked by an ellipsis (…). The lines of a poem when they are run together in an essay are separated by a slash (/).

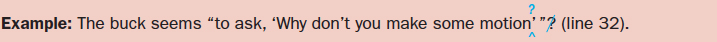

Periods and commas appear within quotation marks. Question marks and exclamation points go within or outside quotation marks, depending on the meaning of the sentence. In the following excerpt, the question mark goes inside the closing quotation marks because it is part of Frost’s poem (line 32). Notice, too, that double and single quotation marks are required for a quotation within a quotation. (See Chapter 24, pp. 608–12 for more on incorporating quotations into your writing.)

|