The American Promise:

Printed Page 381

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 364

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

As the 1852 election approached, the Democrats and Whigs sought to close the sectional rifts that had opened within their parties. For their presidential nominee, the Democrats turned to Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire. Pierce’s well-

Eager to leave the sectional controversy behind, the new president turned swiftly to foreign expansion. Manifest destiny remained robust. (See “Beyond America’s Borders.”) Pierce’s major objective was Cuba, which was owned by Spain and in which slavery flourished, but when antislavery Northerners blocked Cuba’s acquisition to keep more slave territory from entering the Union, Pierce turned to Mexico. In 1853, diplomat James Gadsden negotiated a $10 million purchase of some 30,000 square miles of land in present-

Illinois’s Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas badly wanted the transcontinental railroad for Chicago. Any railroad that ran west from Chicago would pass through a region that Congress in 1830 had designated a “permanent” Indian reserve (see “Indian Policy and the Trail of Tears” in chapter 11). Douglas proposed giving this vast area between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains an Indian name, Nebraska, and then throwing the Indians out. Once the region achieved territorial status, whites could survey and sell the land, establish a civil government, and build a railroad.

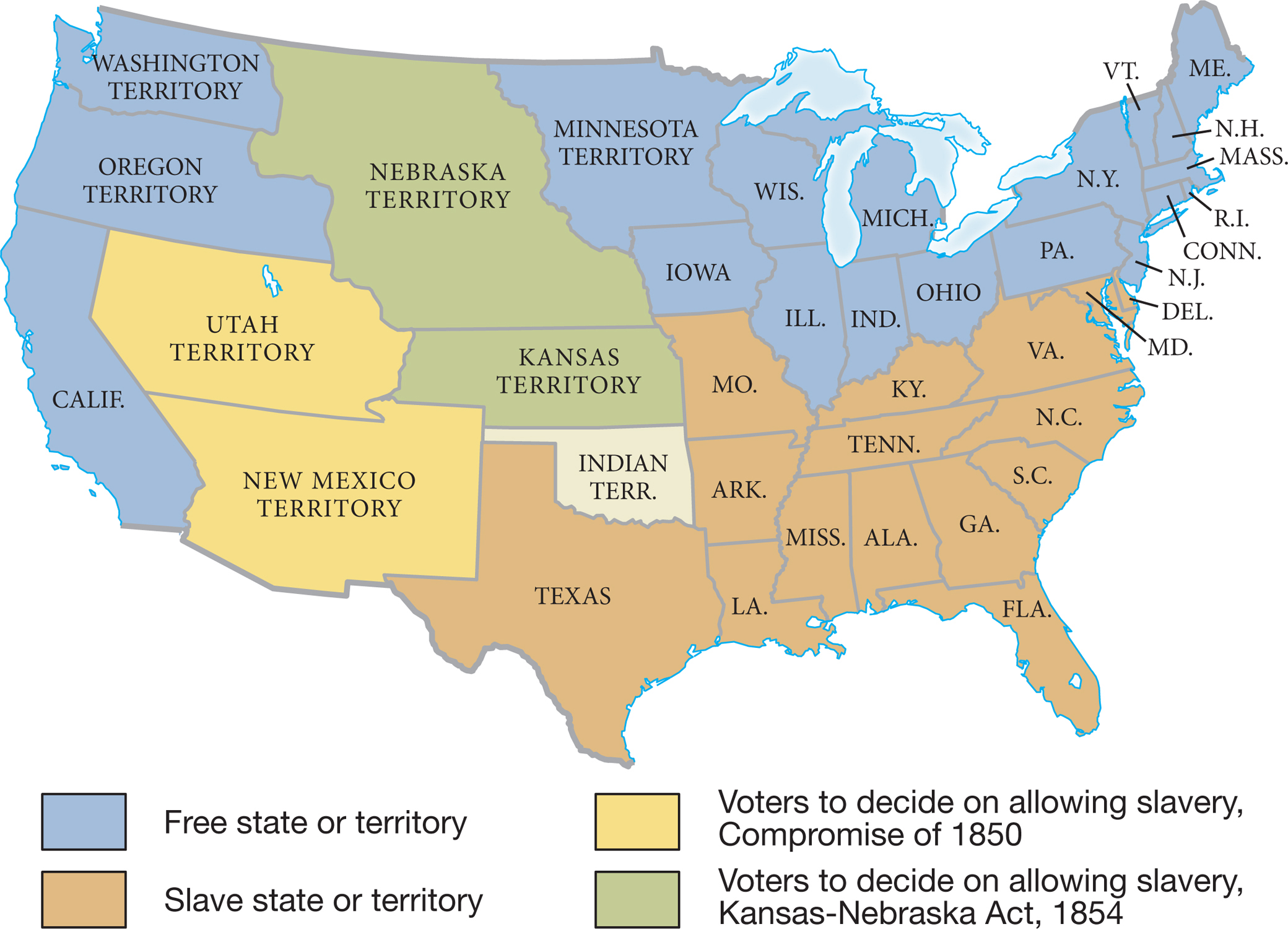

Nebraska lay within the Louisiana Purchase and, according to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, was closed to slavery (see “The Missouri Compromise” in chapter 10). Douglas needed southern votes to pass his Nebraska legislation, but Southerners had no incentive to create another free territory or to help a northern city win the transcontinental railroad. Southerners, however, agreed to help if Congress organized Nebraska according to popular sovereignty. That meant giving slavery a chance in Nebraska Territory and reopening the dangerous issue of slavery expansion.

In January 1854, Douglas introduced his bill to organize Nebraska Territory, leaving to the settlers themselves the decision about slavery. At southern insistence, and even though he knew it would “raise a hell of a storm,” Douglas added an explicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Free-

Undaunted, Douglas skillfully shepherded the explosive bill through Congress in May 1854. Nine-

REVIEW Why did the Compromise of 1850 fail to achieve sectional peace?