The American Promise:

Printed Page 583

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 550

Introduction for Chapter 21

21

Progressivism from the Grass Roots to the White House

1890–1916

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

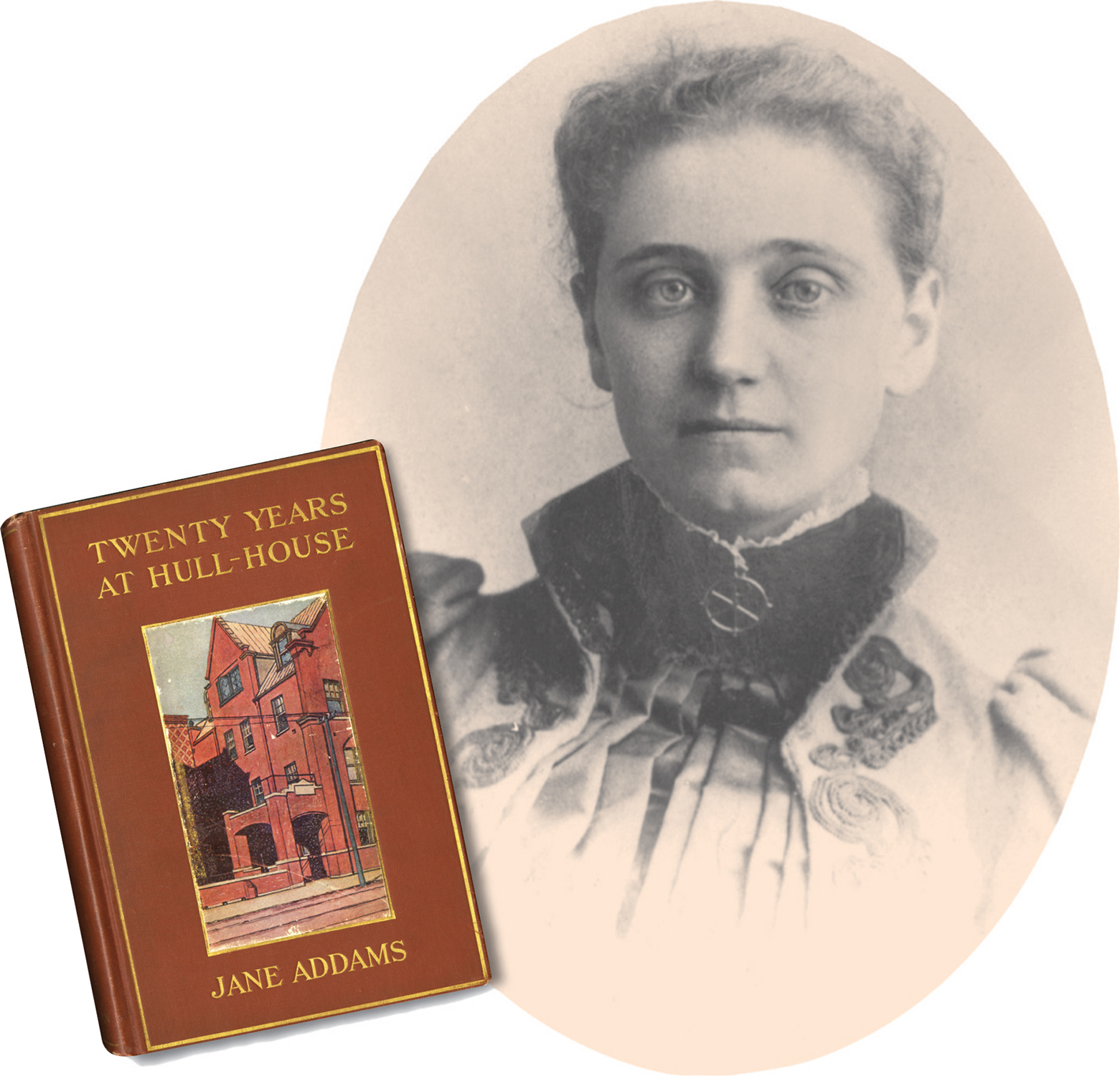

- Explain how and why grassroots progressivism arose near the start of the twentieth century and why proponents like Jane Addams and Hull House served as a spearhead for reform.

- Identify how President Theodore Roosevelt put his progressive activism to work toward big business, conservation, and international affairs and how successor Howard Taft stalled the progressive reforms Roosevelt had begun.

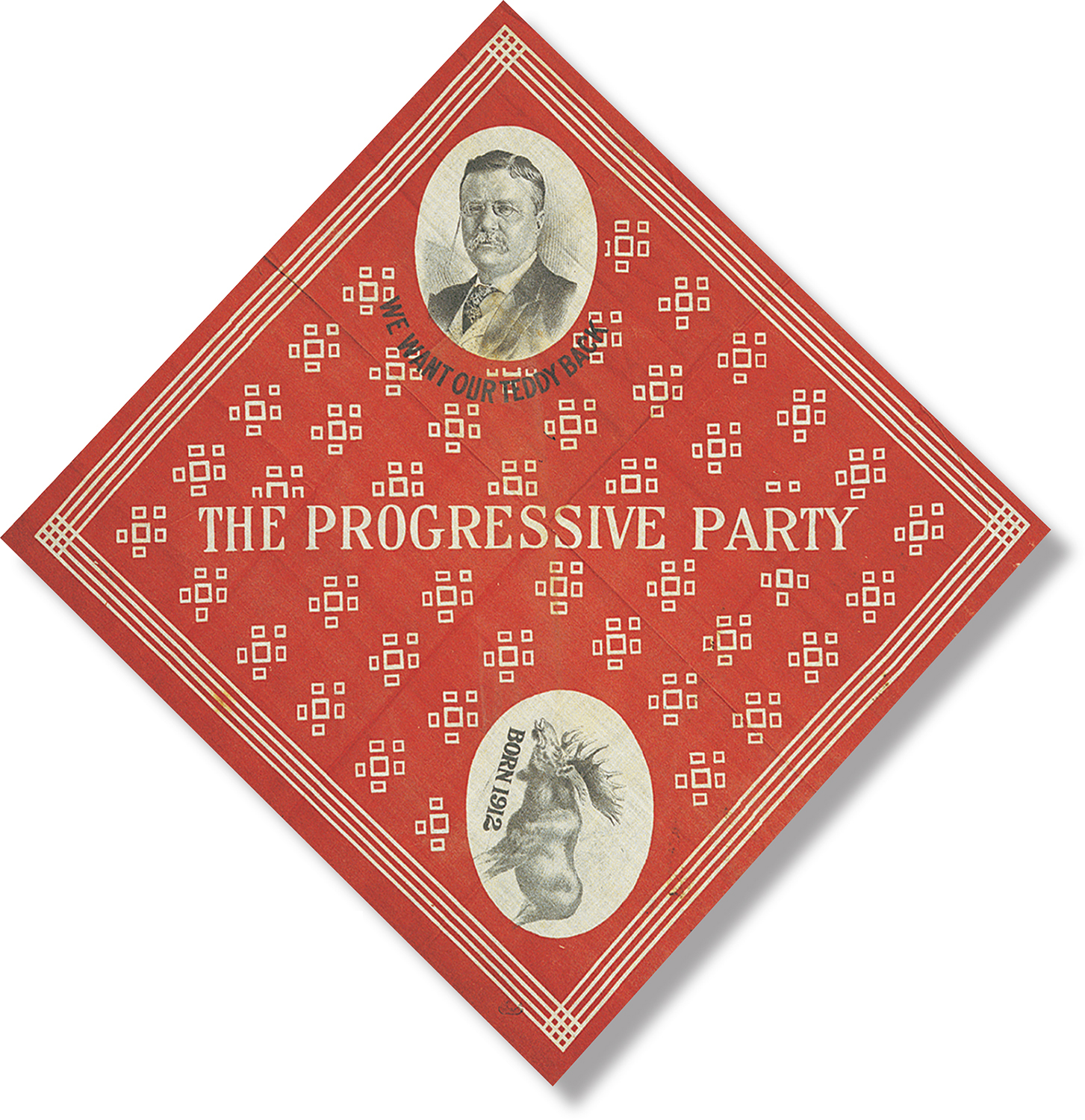

- Explain why progressives led an insurgent campaign during the election of 1912 and the factors that led to Woodrow Wilson’s victory in 1912.

- Describe how Wilson sought to enact his “New Freedom” once in office and explain how he became a reluctant Progressive.

- Understand the limits of progressive reform, and identify the organizations that offered more radical visions of America’s future.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1889, JANE ADDAMS LEASED TWO FLOORS OF A dilapidated mansion on Chicago’s West Side. Her immigrant neighbors must have wondered why this well-

For Addams, personal action marked the first step in her search for solutions to the social problems created by urban industrialism. She wanted to help her immigrant neighbors, and she wanted to offer meaningful work to educated women like herself. Addams’s emphasis on the reciprocal relationship between the social classes made Hull House different from other philanthropic enterprises. She wished to do things with, not just for, Chicago’s poor.

In the next decade, Hull House expanded from two rented floors in the old brick mansion to some thirteen buildings housing a remarkable variety of activities. Addams provided public baths, opened a restaurant for working women too tired to cook after their long shifts, and sponsored a nursery and kindergarten. Hull House offered classes, lectures, art exhibits, musical instruction, and college extension courses. It boasted a gymnasium, a theater, a manual training workshop, a labor museum, and the first public playground in Chicago.

From the first, Hull House attracted an extraordinary set of reformers who pioneered the scientific investigation of urban ills. Armed with statistics, they launched campaigns to improve housing, end child labor, fund playgrounds, and lobby for laws to protect workers.

Addams quickly learned that it was impossible to deal with urban problems without becoming involved in politics. Piles of decaying garbage overflowed Halsted Street’s wooden trash bins, breeding flies and disease. To rectify the problem, Addams got herself appointed garbage inspector. Out on the streets at six in the morning, she rode atop the garbage wagon to make sure it made its rounds. Eventually, her struggle to aid the urban poor led her on to the state capitol and to Washington, D.C.

Under Addams’s leadership, Hull House became a “spearhead for reform,” part of a broader movement that contemporaries called progressivism. The transition from personal action to political activism that Addams personified became one of the hallmarks of this reform period, which lasted from the 1890s to World War I.

Classical liberalism, which opposed the tyranny of centralized government, did not address the enormous power of Gilded Age business giants. As the gap between rich and poor widened in the 1890s, progressive reformers demonstrated a willingness to use the government to counterbalance the power of private interests and, in doing so, redefined liberalism in the twentieth century.

Faith in activism united an otherwise diverse group of progressive reformers. A sense of Christian mission inspired some. Others, fearing social upheaval, sought to remove some of the worst evils of urban industrialism—

Progressives shared a growing concern about the power of wealthy individuals and a distrust of the trusts, but they were not immune to the prejudices of their era. Although they called for greater democracy, many progressives sought to restrict the rights of African Americans, Asians, and even the women who formed the backbone of the movement.

Uplift and efficiency, social justice and social control, direct democracy and discrimination all came together in the Progressive Era at every level of politics and in the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. While in office, Roosevelt advocated conservation, pushed through antitrust reforms, and championed the nation as a world power. Roosevelt’s successor, William Taft, failed to follow in Roosevelt’s footsteps, and the resulting split in the Republican Party paved the way for Wilson’s victory in 1912. A reluctant progressive, Wilson eventually presided over reforms in banking, business, and labor.

CHRONOLOGY

| 1889 |

|

| 1896 |

|

| 1900 |

|

| 1901 |

|

| 1902 |

|

| 1903 |

|

| 1904 |

|

| 1905 |

|

| 1906 |

|

| 1907 |

|

| 1908 |

|

| 1909 |

|

| 1911 |

|

| 1912 |

|

| 1913 |

|

| 1914 |

|

| 1916 |

|