The American Promise:

Printed Page 596

VISUALIZING HISTORY

The Birth of Photojournalism

Photography changed the way Americans viewed their world. By the 1890s, any amateur could purchase the Kodak camera that George Eastman marketed with the slogan “You push the button, we do the rest.” As the poet Oliver Wendell Holmes observed, the camera became not just “the mirror of reality” but “the mirror with a memory.”

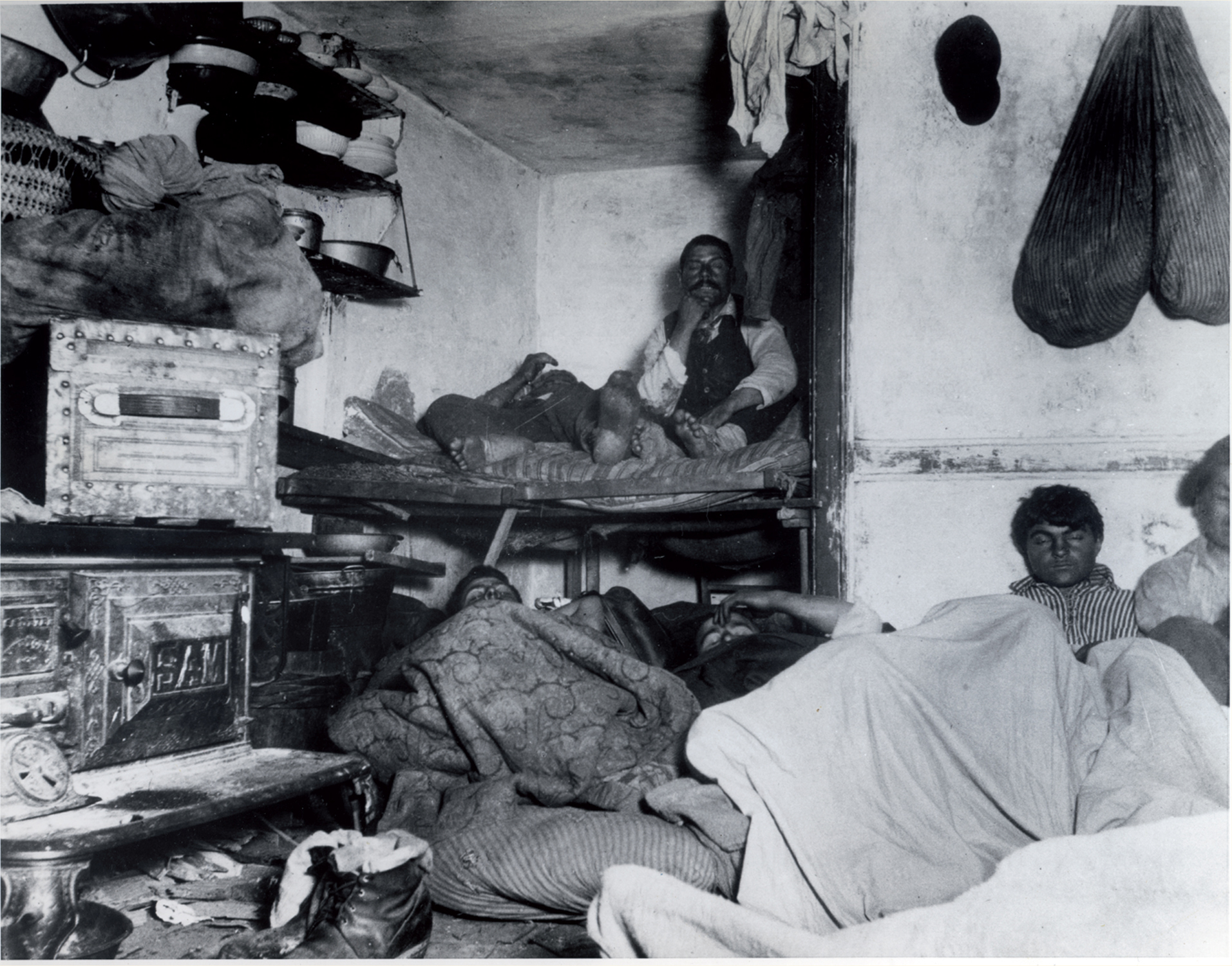

Yet for Jacob Riis, a progressive reformer wishing to document the grim horrors of tenement life, photography was useless because it required daylight or careful studio lighting. He could only crudely sketch the dim hovels, the criminal nightlife, and the windowless tenement rooms of New York. Then came the breakthrough: “One morning scanning my newspaper at my breakfast table, I put it down with an outcry. . . .

Riis set out to shine light in the dark corners of New York. “Our party carried terror wherever it went,” Riis recalled. “The spectacle of strange men invading a house in the midnight hours armed with [flash] pistols which they shot off recklessly was hardly reassuring.” But the results were a huge step forward for photojournalism.

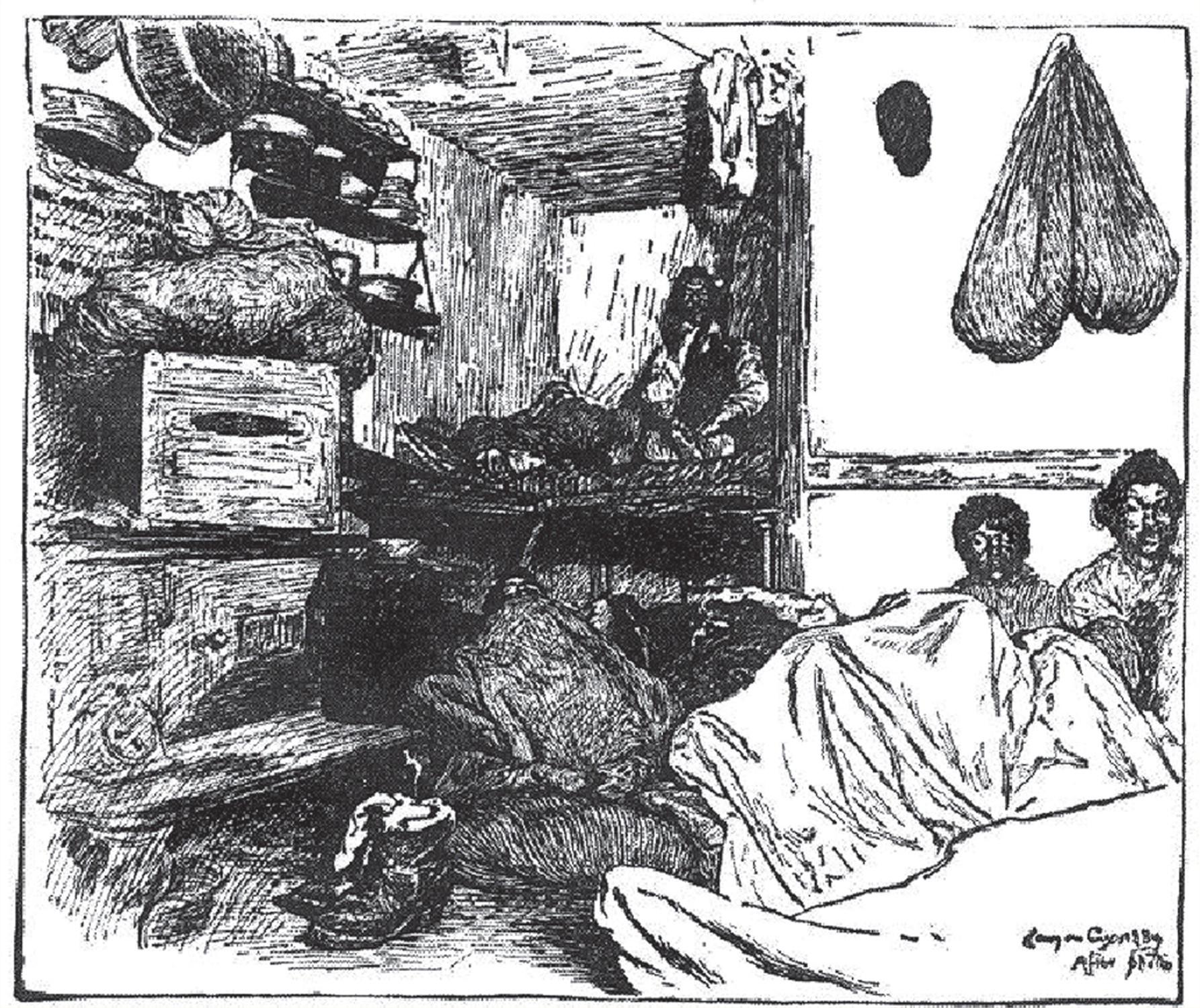

Riis’s book How the Other Half Lives (1890) made photographic history. Along with Riis’s text and engravings of his drawings, it contained reproductions of seventeen photographs taken with his camera and flash. By looking at a line drawing side by side with the corresponding photograph, we can compare the impact of the two mediums. Look at Riis’s line drawing of a “Five Cents a Spot” lodgers’ tenement that appeared in How the Other Half Lives and compare it with the photograph. On a police raid to evict tenement lodgers, Riis describes the room as “not thirteen feet either way,” in which “slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor.” Note how the flash catches the sleepy faces and tired bodies, the crowding, dirt, and disorder.

Riis’s pioneering photojournalism shocked the nation and led not only to tenement reform but also to the development of city playgrounds, neighborhood parks, and child labor laws.

SOURCE: Five Cents a Spot, drawing and photo: Library of Congress.

Questions for Analysis

- How do you think photography affected American memory?

- What details visible in the photograph are lost in the drawing? Which portrayal has a greater impact on the viewer?

- Would you agree that Riis’s photographs are “a mirror of reality,” or did he interpret and frame the “reality” he photographed?

Connect to the Big Idea

How was photojournalism part of the progressive movement?