The American Promise:

Printed Page 600

HISTORICAL QUESTION

Progressives and Conservation: Should Hetch Hetchy Be Dammed or Saved?

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed into law an act setting aside two million acres in California’s Yosemite Valley and designating Yosemite a national park. For naturalist John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, the act marked a victory in his crusade to guarantee that “incomparable Yosemite” would be preserved for posterity. But Muir’s fight was not yet over.

The growing city of San Francisco needed water and power, and Mayor James Phelan soon sought to obtain water rights in Hetch Hetchy, a spectacular mountain valley within Yosemite’s borders. There, the Tuolumne River could easily be dammed and the valley flooded to create a reservoir large enough to ensure the city’s water supply for one hundred years.

When Muir heard of the plan, he sprang into action to save Hetch Hetchy. “That any one would try to destroy such a place seems incredible,” he wrote, describing the valley as “one of Nature’s rarest and most precious mountain temples.” All of Yosemite National Park, he argued, should remain sacrosanct. In 1903, the secretary of the interior concurred, denying San Francisco supervisors commercial use of Hetch Hetchy on the grounds that it lay within the national park.

But the San Francisco earthquake and resulting fire in 1906 created a groundswell of sympathy for the devastated city. In this climate, San Francisco renewed its efforts to obtain Hetch Hetchy and, in 1907, succeeded in gaining authorization to proceed with plans to dam the river and flood the valley.

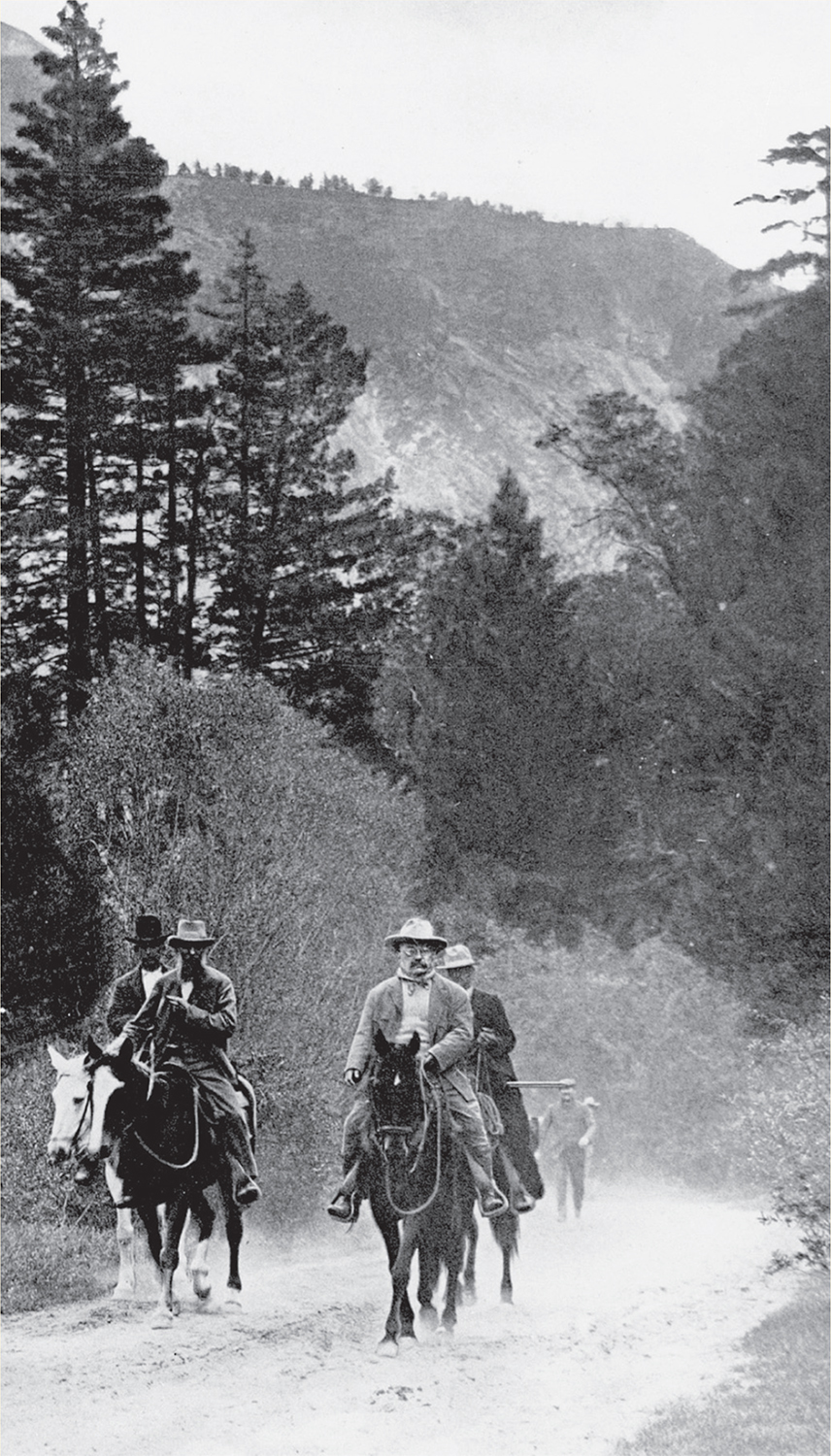

Given President Theodore Roosevelt’s commitment to conservation, how could his administration have agreed to the destruction of the Hetch Hetchy valley? Historians traditionally have styled the struggle as one that pitted conservationists against preservationists. Roosevelt’s chief forester, Gifford Pinchot, represented the forces of conservation, or managed use. To him, the battle was not over preservation but over public versus private control of water and power. Roosevelt somewhat reluctantly agreed, although he softened the blow by designating a redwood sanctuary north of San Francisco a national monument in 1907 and naming it Muir Woods.

California progressives, who swept into office with the election of Hiram Johnson as governor in 1910, argued that if Congress did not grant the city of San Francisco the right to control Hetch Hetchy, the powerful Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) would monopolize the city’s light and power industry. These progressives dismissed Muir and his followers as “nature fakers” and judged them little more than dupes in the machinations of PG&E.

For their part, Muir and the preservationists, although they fought for the integrity of the national parks, did not champion the preservation of wilderness for its own sake. The urban professional men and women who joined the Sierra Club saw nature as a retreat and restorative for city dwellers. The club hosted an annual camping trip to popularize Yosemite and spoke in glowing terms of plans to build new roads and hotels that would make the “healing power of Nature” accessible to “thousands of tired, nerve-

Nevertheless, the engineers and irrigation men who dammed Hetch Hetchy demonstrated a breathtaking arrogance. Speaking for them, Franklin Lane, interior secretary under Woodrow Wilson, proclaimed, “The mountains are our enemy. We must pierce them and make them serve. The sinful rivers we must curb.” Lane and the conservationists won the day. In 1913, Congress passed the Raker Act authorizing the building of the O’Shaughnessy Dam, completed a decade later. To build the dam, the Hetch Hetchy valley was first denuded of its trees and then flooded under two hundred feet of water. Muir did not live to see the destruction of Hetch Hetchy. He died in 1914, cursing the “dark damn-

The last chapter in the battle over Hetch Hetchy may yet be written. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan’s secretary of the interior, Donald Hodel, shocked San Francisco by suggesting the removal of the O’Shaughnessy Dam and the restoration of the Hetch Hetchy valley. Although it is unlikely that the dam will be demolished (it supplies San Francisco not only with water but also with revenue from electric power), advocates for the restoration of the Hetch Hetchy valley continue to rally to the cause. As Ken Browner of the Sierra Club wrote, “Waiting in Yosemite National Park, under water, is a potential masterpiece of restoration” and a chance “to correct the biggest environmental mistake ever committed against the National Park System.”

Questions for Consideration

- What does the damming of Hetch Hetchy tell us about the Roosevelt administration’s conservation policies in the West?

- Given Roosevelt’s conservation policies overall, are critics right in accusing him of failing to preserve the wilderness?

Connect to the Big Idea

How did the goals of Progressive Era conservationists and preservationists differ?