The American Promise:

Printed Page 604

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 567

Progressive Insurgency and the Election of 1912

Convinced that Taft was inept, in February 1912, Roosevelt announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination announcing “My hat is in the ring.” Taft, with uncharacteristic strength, refused to step aside. Roosevelt took advantage of newly passed primary election laws and ran in thirteen states, winning 278 delegates to Taft’s 48. But at the Chicago convention, Taft’s bosses refused to seat the Roosevelt delegates. Fistfights broke out on the convention floor as Taft won nomination on the first ballot. Crying robbery, Roosevelt’s supporters bolted the party.

Seven weeks later, in the same Chicago auditorium, the hastily organized Progressive Party met to nominate Roosevelt. Full of reforming zeal, the delegates chose Roosevelt and Hiram Johnson to head the new party. Jane Addams seconded Roosevelt’s nomination. “I have been fighting for progressive principles for thirty years,” she told the enthusiastic crowd. “This is the first time there has been a chance to make them effective. This is the biggest day of my life.” The new party lustily approved the most ambitious platform since that of the Populists. Planks called for woman suffrage, presidential primaries, conservation of natural resources, an end to child labor, workers’ compensation, a living wage for both men and women workers, social security, health insurance, and a federal income tax.

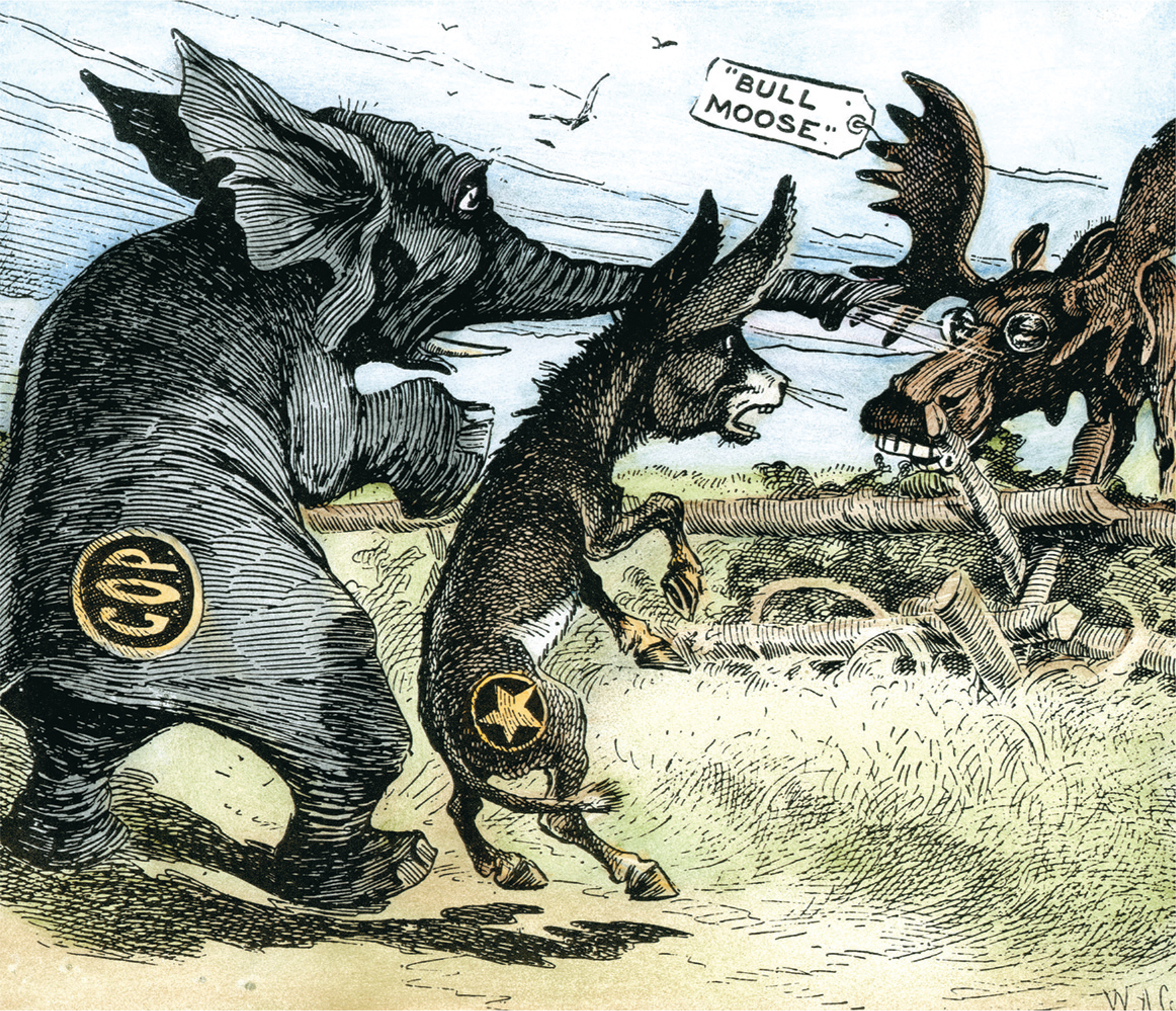

Roosevelt arrived in Chicago to accept the nomination and announced that he felt “as fit as a bull moose,” giving the new party a nickname and a mascot. With characteristic vigor, he launched his campaign with the exhortation, “We stand at Armageddon and do battle for the Lord!” But for all the excitement and the cheering, the new Progressive Party was doomed, and the candidate knew it. Privately he confessed to a friend, “I am under no illusion about it. It is a forlorn hope.” The people may have supported the party, but the politicians, even progressives such as La Follette, refused to support the new party. The Democrats, delighted at the split in the Republican ranks, nominated Woodrow Wilson, the governor of New Jersey. After only eighteen months in office, the former professor of political science and president of Princeton University found himself running for president of the United States.

Voters in 1912 could choose among four candidates who claimed to be progressives. Taft, Roosevelt, and Wilson each embraced the label, and even the Socialist candidate, Eugene V. Debs, styled himself a progressive. That the term progressive could stretch to cover these diverse candidates underscored major disagreements in progressive thinking about the relationship between business and government. Taft, in spite of his trust-

The New Nationalism expressed Roosevelt’s belief in federal planning and regulation. He accepted the inevitability of big business but demanded that government act as “a steward of the people” to regulate the giant corporations. Wilson, schooled in the Democratic principles of limited government and states’ rights, set a markedly different course with his New Freedom. Wilson promised to use antitrust legislation to get rid of big corporations and to give small businesses and farmers better opportunities in the marketplace.

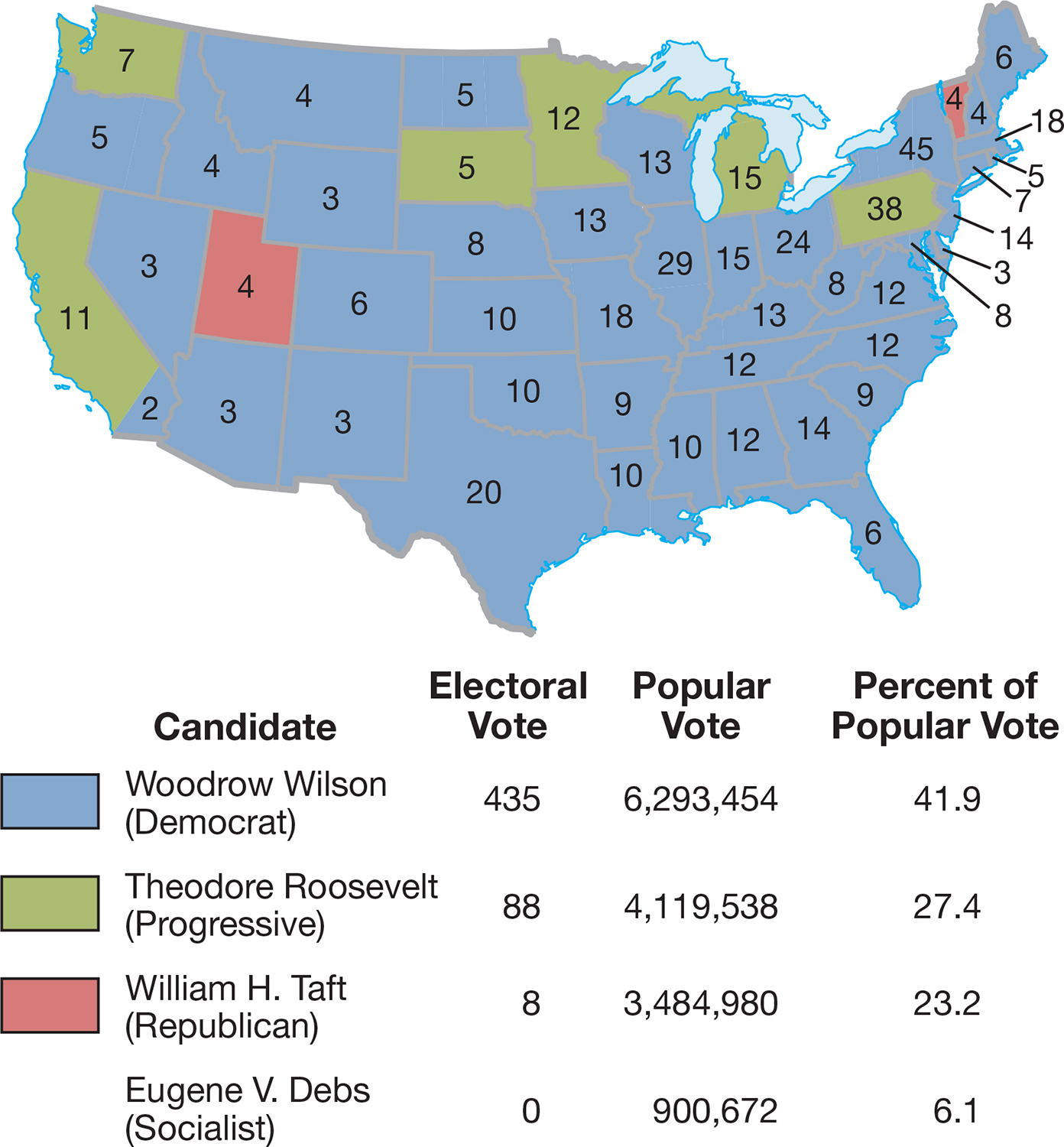

The energy and enthusiasm of the Bull Moosers made the race seem closer than it was. In the end, the Republican vote split, while the Democrats remained united. No candidate claimed a majority in the race. Wilson captured a bare 42 percent of the popular vote. Roosevelt and his Bull Moose Party won 27 percent, an unprecedented tally for a new party. Taft came in third with 23 percent. The Socialist Party, led by Debs, captured a surprising 6 percent (Map 21.3). The Republican Party moved in a conservative direction, while the Progressive Party essentially collapsed after Roosevelt’s defeat. It had always been, in the words of one astute observer, “a house divided against itself and already mortgaged.”