The American Promise:

Printed Page 774

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 721

Interventions in Latin America and the Middle East

While supporting friendly governments in Asia, the Eisenhower administration sought to topple unfriendly ones in Latin America and the Middle East. Officials saw internal civil wars in terms of the Cold War conflict between the superpowers and often viewed nationalist uprisings as Communist threats to democracy. They also acted against governments that threatened U.S. economic interests. The Eisenhower administration took this course of action out of sight of Congress and the public, making the CIA an important arm of foreign policy.

Guatemala’s government, under the popularly elected reformist president Jacobo Arbenz, was not Soviet controlled, but it accepted support from the small local Communist Party (see “Meeting the ‘Hour of Maximum Danger’” in chapter 29, Map 29.1). In 1953, Arbenz moved to help landless, poverty-

In 1959, when Cubans’ desire for political and economic autonomy erupted into a revolution led by Fidel Castro, a CIA agent promised “to take care of Castro just like we took care of Arbenz.” American companies controlled major Cuban resources, and decisions made in Washington directly influenced the lives of the Cuban people. The 1959 Cuban revolution drove out the U.S.-supported dictator Fulgencio Batista and led the CIA to warn Eisenhower that “Communists and other extreme radicals appear to have penetrated the Castro movement.” When the United States denied Castro’s requests for loans, he turned to the Soviet Union. And when U.S. companies refused Castro’s offer to purchase their Cuban holdings at their assessed value, he began to nationalize their property. Many anti-

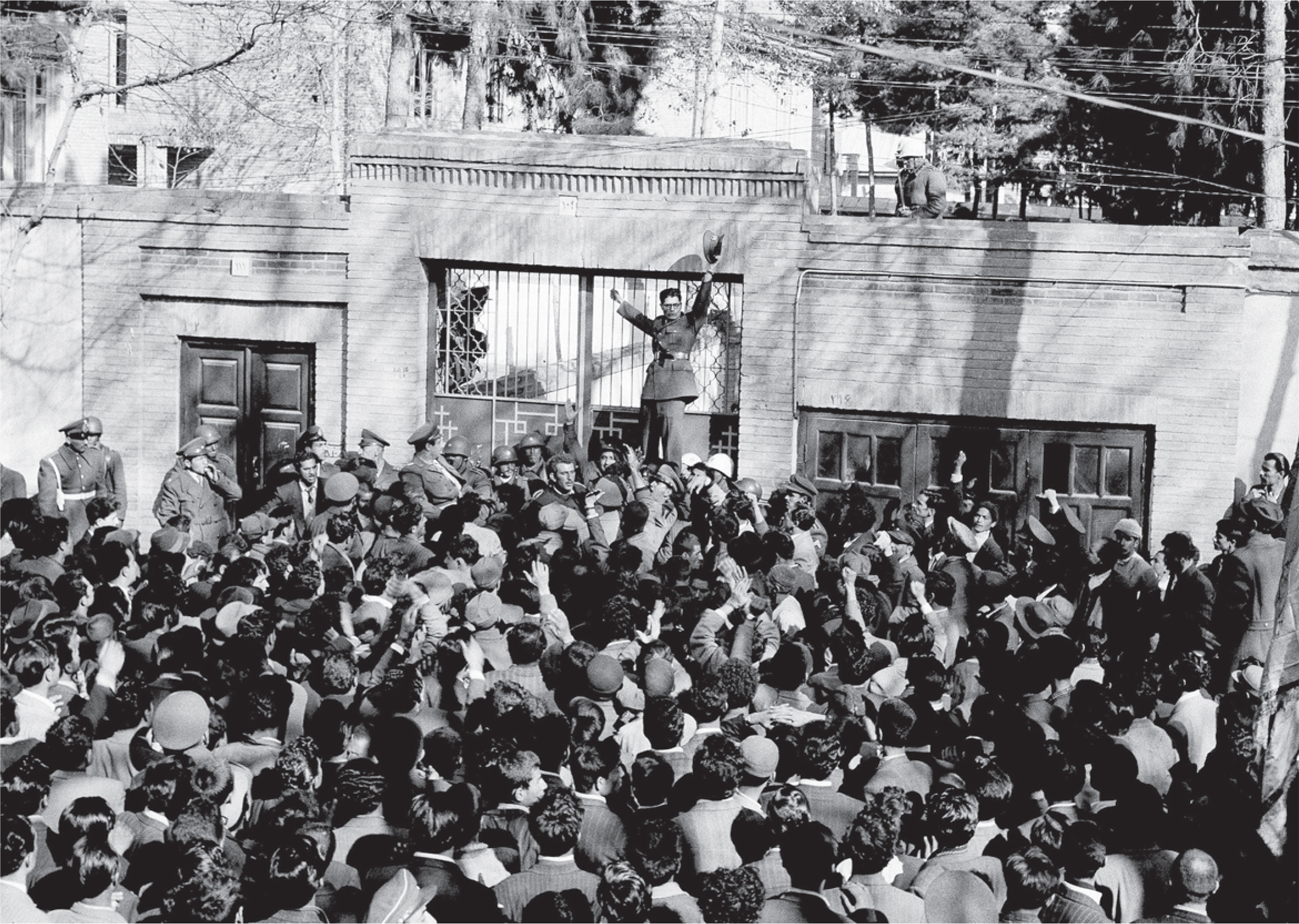

In the Middle East, the CIA intervened in Iran to oust an elected government, support an unpopular dictatorship, and maintain Western access to Iranian oil (see “The Cold War Intensifies” in chapter 30, Map 30.3). In 1951, the Iranian parliament, led by Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, nationalized the country’s oil fields and refineries, which had been held primarily by a British company and from which Iran received less than 20 percent of profits. Britain strongly objected to the takeover and eventually sought help from the United States.

Advisers convinced Eisenhower that Mossadegh, whom Time magazine had called “the Iranian George Washington,” left Iran vulnerable to communism, and the president wanted to keep oil-

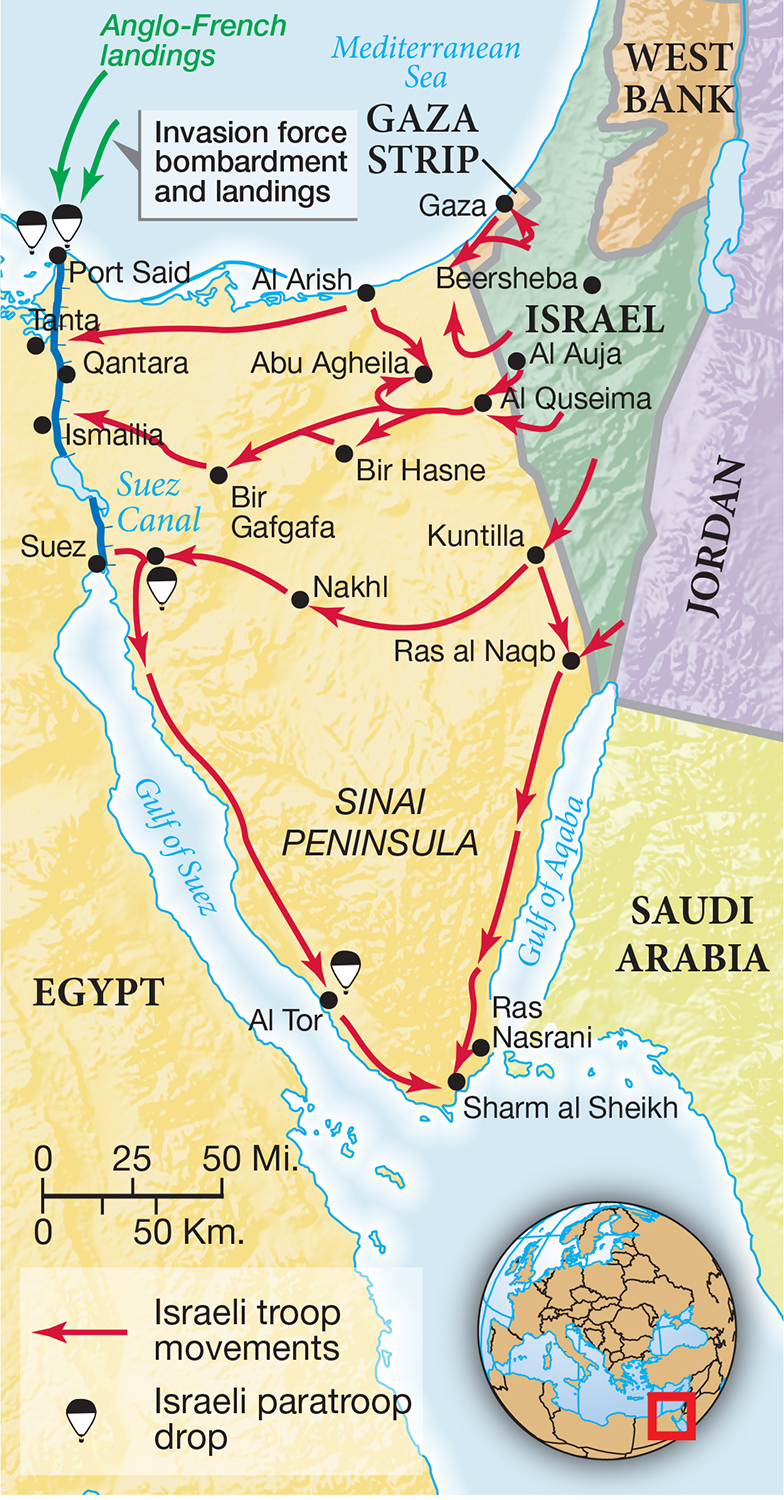

Elsewhere in the Middle East, Eisenhower continued Truman’s support of Israel but also pursued friendships with Arab nations to secure access to oil and build a bulwark against communism. U.S. officials demanded that smaller nations take the American side in the Cold War, even when those nations preferred neutrality. In 1955, as part of this effort to win Arab allies, Secretary of State Dulles began talks with Egypt about American support to build the Aswan Dam on the Nile River. The following year, Egypt’s leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, sought arms from Communist Czechoslovakia, formed a military alliance with other Arab nations, and recognized the People’s Republic of China. In retaliation, Dulles called off the deal for the dam.

In July 1956, Nasser responded by seizing the Suez Canal, then owned by Britain and France but scheduled to revert to Egypt within seven years. In response to the seizure, Israel, whose forces had been skirmishing with Egyptian troops along their common border since 1948, attacked Egypt, with help from Britain and France. Eisenhower opposed the intervention, recognizing that the Egyptians had claimed their own territory and that Nasser “embodie[d] the emotional demands of the people . . .

Despite staying out of the Suez crisis, Eisenhower made it clear in a January 1957 speech that the United States would actively combat communism in the Middle East. In March, Congress approved aid to any Middle Eastern nation “requesting assistance against armed aggression from any country controlled by international communism.” The president invoked this Eisenhower Doctrine to send aid to Jordan in 1957 and troops to Lebanon in 1958 to counter anti-