The American Promise:

Printed Page 870

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 807

Chapter Chronology

The Cold War Intensifies

Consistent with his human rights approach, Carter preferred to pursue national security through nonmilitary means and initially sought accommodation with the nation’s Cold War enemies. Following up on Nixon’s initiatives, in 1979 he opened formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China and signed a second strategic arms reduction treaty with Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev.

Yet that same year, Carter decided to pursue a military buildup when the Soviet Union invaded neighboring Afghanistan, whose recently installed Communist government was threatened by Muslim opposition (see Map 30.3). Carter imposed economic sanctions on the Soviet Union, barred U.S. participation in the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow, and obtained legislation requiring all nineteen-year-old men to register for the draft.

Claiming that Soviet actions jeopardized oil supplies from the Middle East, the president announced the “Carter Doctrine,” threatening the use of any means necessary to prevent an outside force from gaining control of the Persian Gulf. His human rights policy fell by the way-side as the United States stepped up aid to the military dictatorship in Afghanistan’s neighbor, Pakistan, and the CIA funneled secret aid through Pakistan to the Afghan rebels. Finally, Carter called for hefty increases in defense spending.

Events in Iran also encouraged this hard-line approach. Generous U.S. arms and aid had not enabled the shah to crush Iranian dissidents who still resented the CIA’s role in the overthrow of the Mossadegh government in 1953 (see “Interventions in Latin America and the Middle East” in chapter 27), condemned the shah’s brutal attempts to silence opposition, and detested his adoption of Western culture and values. These grievances erupted into a revolution in 1979 that forced the shah out of Iran and brought to power Shiite Islamic fundamentalists led by Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini, whom the shah had exiled in 1964.

Carter’s decision to allow the shah into the United States for medical treatment enraged Iranians, who believed that the United States would restore the shah to power as it had done in 1953. On November 4, 1979, a crowd broke into the U.S. Embassy in Iran’s capital, Teheran, and seized sixty-six U.S. diplomats, CIA officers, citizens, and military attachés. Refusing the captors’ demands that the shah be returned to Iran for trial, Carter froze Iranian assets in U.S. banks and placed an embargo on Iranian oil. In April 1980, he sent a small military operation into Iran, but the rescue mission failed.

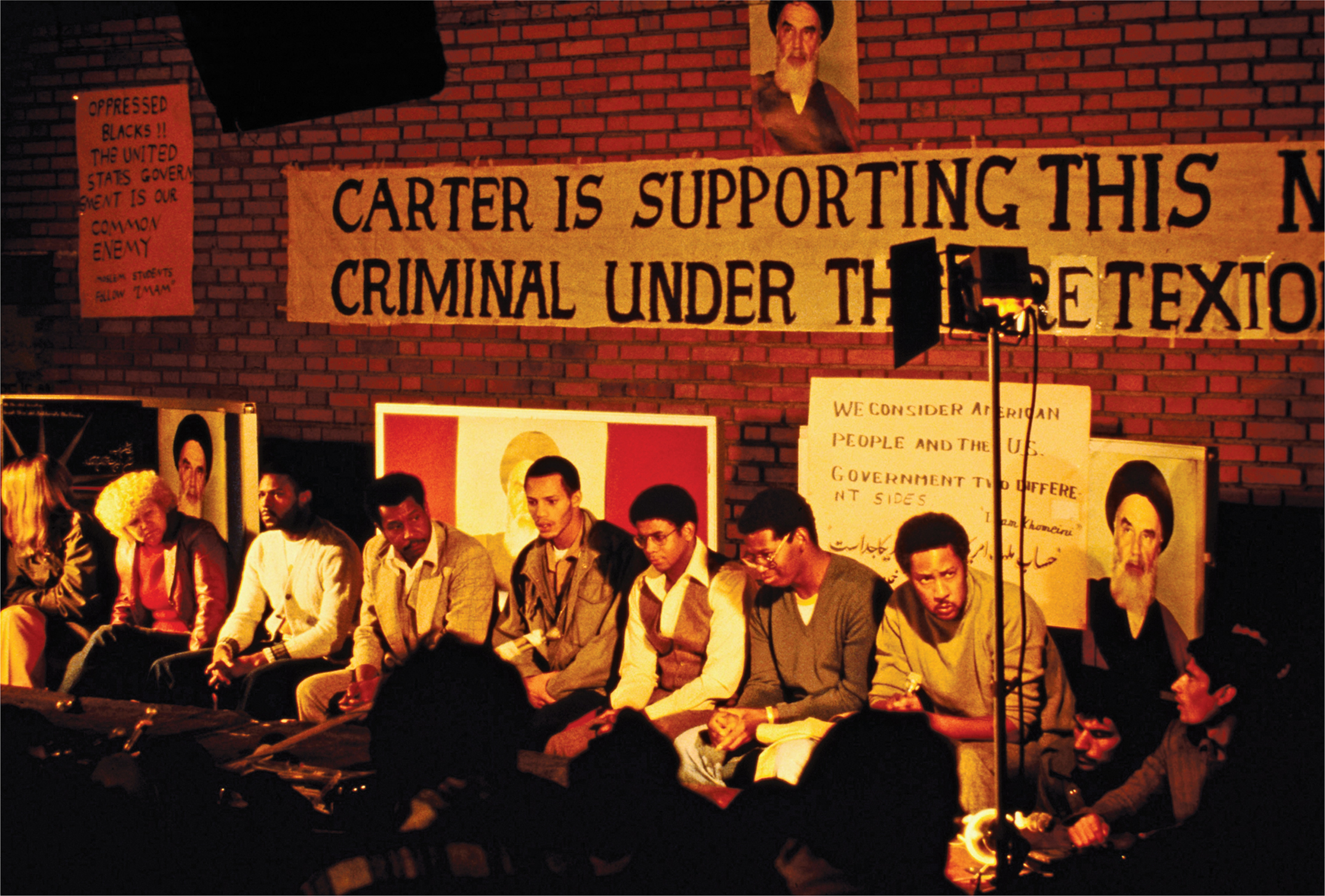

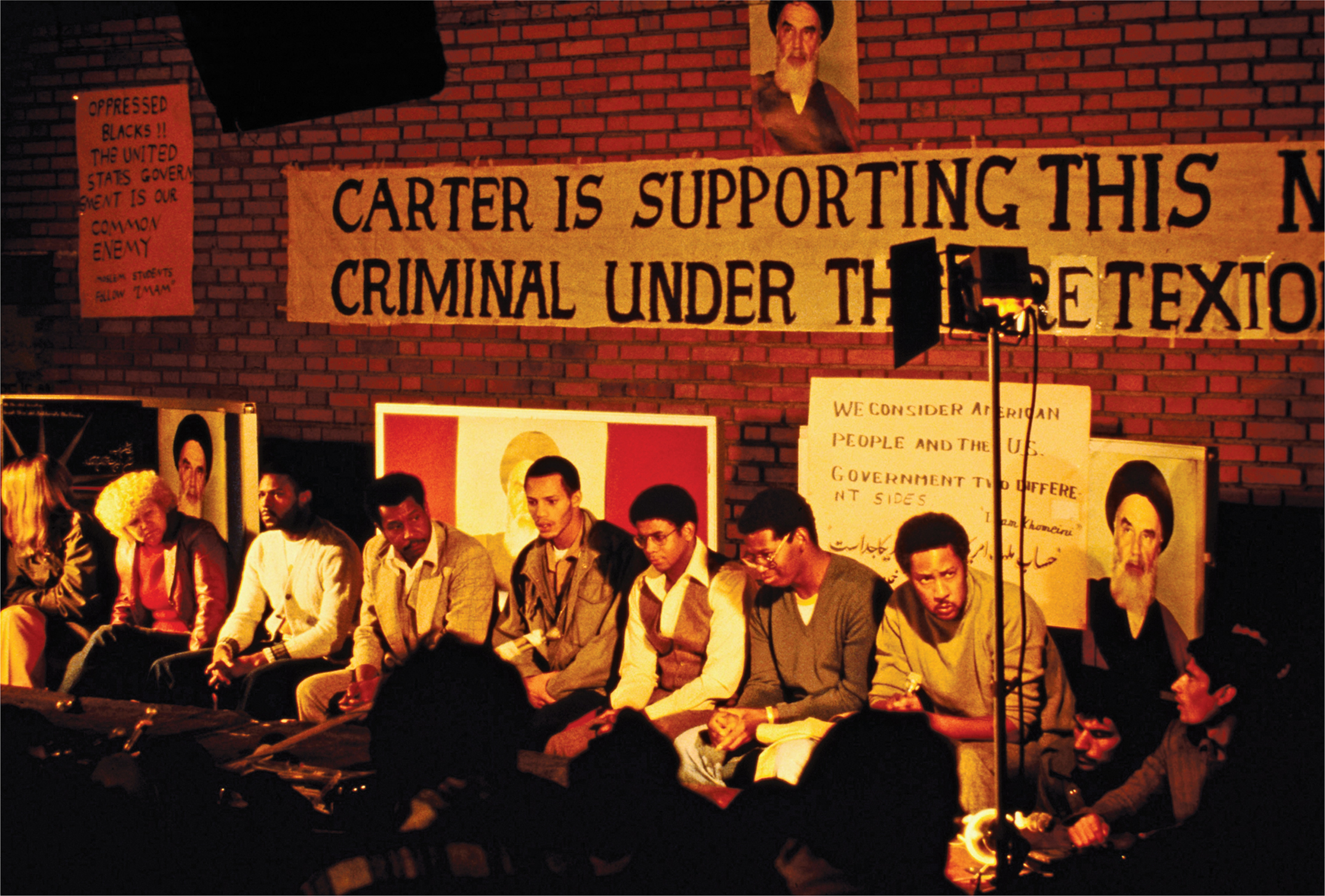

The disastrous rescue attempt and scenes of blindfolded U.S. citizens paraded before TV cameras fed Americans’ feelings of impotence, simmering since the defeat in Vietnam. These frustrations in turn increased support for a more militaristic foreign policy. Opposition to Soviet-American détente, combined with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, nullified the thaw in superpower relations that had begun in the 1960s. Iran released a handful of the captives (primarily women and African Americans), but the Iran hostage crisis dominated the news during the 1980 presidential campaign and contributed to Carter’s defeat. Iran freed the remaining 52 hostages the day he left office, but relations with the United States remained tense.

American Hostages in Iran Less than a month after Iranian militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took Americans hostage, the Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini ordered the release of thirteen hostages, all women or African Americans, because he believed they were not spies and had already endured “the oppression of American society.” Here, in front of propaganda, they are presented to the press shortly before their release. © Bettmann/Corbis.

REVIEW: How did Carter implement his commitment to human rights, and why did human rights give way to other priorities?