Using a Problem-Solving Model for Preparing Recommendation Reports

Printed Page 470-475

Using a Problem-Solving Model for Preparing Recommendation Reports

The writing process for a recommendation report is similar to that for any other technical communication:

- Planning. Analyze your audience, determine your purpose, and visualize the deliverable: the report you will submit. Conduct appropriate secondary and primary research.

- Drafting. Write a draft of the report. Large projects often call for many writers and therefore benefit from shared document spaces and wikis.

- Revising. Think again about your audience and purpose, and then make appropriate changes to your draft.

- Editing. Improve the writing in the report, starting with the largest issues of development and emphasis and working down to the sections, paragraphs, sentences, and individual words.

- Proofreading. Go through the draft slowly, making sure you have written what you wanted to write. Get help from others.

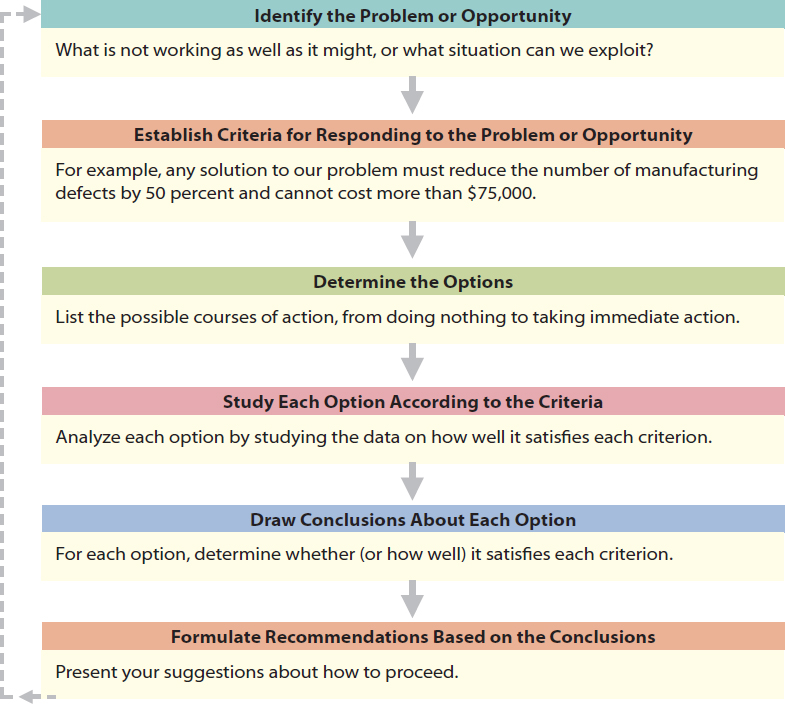

In addition to this model of the writing process, you need a problem-solving model for conducting the analysis that will enable you to write the recommendation report. The following discussion explains in more detail the problem-solving model shown in Figure 18.1.

What is not working or is not working as well as it might? What situation presents an opportunity to decrease costs or improve the quality of a product or service? Without a clear statement of your problem or opportunity, you cannot plan your research.

For example, your company has found that employees who smoke are absent and ill more often than those who don’t smoke. Your supervisor has asked you to investigate whether the company should offer a free smoking-cessation program. The company can offer the program only if the company’s insurance carrier will pay for it. The first thing you need to do is talk with the insurance agent; if the insurance carrier will pay for the program, you can proceed with your investigation. If the agent says no, you have to determine whether another insurance carrier offers better coverage or whether there is some other way to encourage employees to stop smoking.

Criteria are standards against which you measure your options. Criteria can be classified into two categories: necessary and desirable. For example, if you want to buy a photocopier for your business, necessary criteria might be that each copy cost less than two cents to produce and that the photocopier be able to handle oversized documents. If the photocopier doesn’t fulfill those two criteria, you will not consider it further. By contrast, desirable criteria might include that the photocopier be capable of double-sided copying and stapling. Desirable criteria let you make distinctions among a variety of similar objects, objectives, actions, or effects. If a photocopier does not fulfill a desirable criterion, you will still consider it, although it will be less attractive.

Until you establish your criteria, you don’t know what your options are. Sometimes you are given your criteria: your supervisor tells you how much money you can spend, for instance, and that figure becomes one of your necessary criteria. Other times, you derive your criteria from your research.

After you establish your criteria, you determine your options. Options are potential courses of action you can take in responding to a problem or opportunity. Determining your options might be simple or complicated.

Sometimes your options are presented to you. For instance, your supervisor asks you to study two vendors for accounting services and recommend one of them. The options are Vendor A or Vendor B. That’s simple.

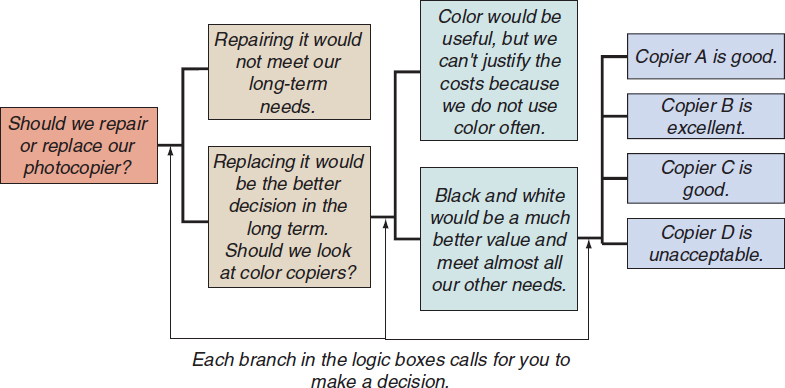

In other cases, you have to consider a series of options. For example, your department’s photocopier is old and breaking down. Your first decision is whether to repair it or replace it. Once you have answered that question, you might have to make more decisions. If you are going to replace it, what features should you look for in a new one? Each time you make a decision, you have to answer more questions until, eventually, you arrive at a recommendation. For a complicated scenario like this, you might find it helpful to use logic boxes or flowcharts to sketch the logic of your options, as shown in Figure 18.2.

As you research your topic, your understanding of your options will likely change. At this point, however, it is useful to understand the basic logic of your options or series of options.

Once you have identified your options (or series of options), study each one according to the criteria. For the photocopier project, secondary research would include studying articles about photocopiers in technical journals and specification sheets from the different manufacturers. Primary research might include observing product demonstrations as well as interviewing representatives from different manufacturers and managers who have purchased different brands.

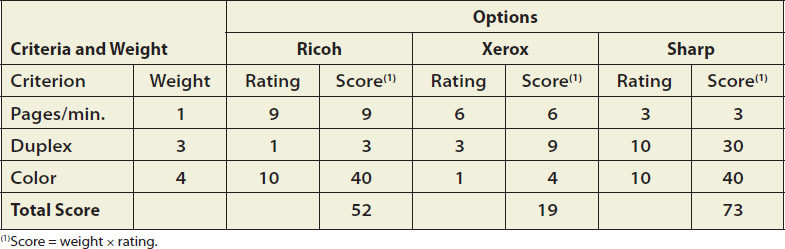

To make the analysis of the options as objective as possible, professionals sometimes create a decision matrix, a tool for systematically evaluating each option according to each criterion. A decision matrix is a table (or a spreadsheet), as shown in Figure 18.3. Here the writer is nearly at the end of his series of options: he is evaluating three similar photocopiers according to three criteria. Each criterion has its own weight, which suggests how important it is. The greater the weight, the more important the criterion.

As shown in Figure 18.3, the criterion of pages per minute is relatively unimportant: it receives a weight of 1. For this reason, the Ricoh copier, even though it receives a high rating for pages per minute (9), receives only a modest score of 9 (1 × 9 = 9) on this criterion. However, the criterion of color copying is quite important, with a weight of 4. On this criterion, the Ricoh, with its rating of 10, achieves a very high score (4 × 10 = 40).

But a decision matrix cannot stand on its own. You need to explain your methods. That is, in the discussion or in footnotes to the matrix, you need to explain the following three decisions:

- Why you chose each criterion—or didn’t choose a criterion the reader might have expected to see included. For instance, why did you choose duplexing (double-sided printing) but not image scanning?

- Why you assigned a particular weight to each criterion. For example, why is the copier’s ability to make color copies four times more important than its speed?

- Why you assigned a particular rating to each option. For example, why does one copier receive a rating of only 1 on duplexing, whereas another receives a 3 and a third receives a 10?

A decision matrix is helpful only if your readers understand your methods and agree with the logic you used in choosing the criteria and assigning the weight and ratings for each option.

Although a decision matrix has its limitations, it is useful for both you and your readers. For you as the writer, the main advantage is that it helps you do a methodical analysis. For your readers, it makes your analysis easier to follow because it clearly presents your methods and results.

Whether you use a decision matrix or a less-formal means of recording your evaluations, the next step is to draw conclusions about the options you studied—by interpreting your results and writing evaluative statements about the options.

For the study of photocopiers, your conclusion might be that the Sharp model is the best copier: it meets all your necessary criteria and the greatest number of desirable criteria, or it scores highest on your matrix. Depending on your readers’ preferences, you can present your conclusions in any one of three ways.

- Rank all the options: the Sharp copier is the best option, the Ricoh copier is second best, and so forth.

- Classify all the options in one of two categories: acceptable and unacceptable.

- Present a compound conclusion: the Sharp offers the most technical capabilities; the Ricoh is the best value.

If you conclude that Option A is better than Option B—and you see no obvious problems with Option A—recommend Option A. But if the problem has changed or your company’s priorities or resources have changed, you might decide to recommend a course of action that is inconsistent with the conclusions you derived. Your responsibility is to use your judgment and recommend the best course of action.

ETHICS NOTE

PRESENTING HONEST RECOMMENDATIONS

As you formulate your recommendations, you might know what your readers want you to say. For example, they might want you to recommend the cheapest option, or one that uses a certain kind of technology, or one that is supplied by a certain vendor. Naturally, you want to be able to recommend what they want, but sometimes the facts won’t let you. Your responsibility is to tell the truth—to do the research honestly and competently and then present the findings honestly. Your name goes on the report. You want to be able to defend your recommendations based on the evidence and your reasoning.

One worrisome situation that arises frequently is that none of the options would be a complete success or none would work at all. What should you do? You should tell the truth about the options, warts and all. Give the best advice you can, even if that advice is to do nothing.