Understanding Conventional Organizational Patterns

Printed Page 149-165

Understanding Conventional Organizational Patterns

Every argument calls for its own organizational pattern. Table 7.1 explains the relationship between organizational patterns and the kinds of information you want to present.

| TABLE 7.1 Organizational Patterns and the Kinds of Information You Want To Present | ||

| IF YOU WANT TO . . . | CONSIDER USING THIS ORGANIZATIONAL PATTERN | FOR EXAMPLE . . . |

| Explain events that occurred or might occur or tasks that the reader is to carry out | Chronological. Most of the time, you present information in chronological order. Sometimes, however, you use reverse chronology. | You describe the process used to diagnose the problem with the accounting software. Or, in a résumé, you describe your more-recent jobs before your earlier ones. |

| Describe a physical object or scene, such as a device or a location | Spatial. You choose an organizing principle such as top-to-bottom, east-to-west, or inside-to-outside. | You describe the three main buildings that will make up the new production facility. |

| Explain a complex situation, such as the factors that led to a problem or the theory that underlies a process | General to specific. You present general information first, then specific information. Understanding the big picture helps readers understand the details. | You explain the major changes and the details of a law mandating the use of a new refrigerant in cooling systems. |

| Present a set of factors | More important to less important. You discuss the most-important issue first, then the next-most-important issue, and so forth. In technical communication, you don’t want to create suspense. You want to present the most-important information first. | When you launch a new product, you discuss market niche, competition, and then pricing. |

| Present similarities and differences between two or more items | Comparison and contrast. You choose from one of two patterns: (1) discuss all the factors related to one item, then all the factors related to the next item, and so forth; (2) discuss one factor as it relates to all the items, then another factor as it relates to all the items, and so forth. | You discuss the strengths and weaknesses of three companies bidding on a contract your company is offering. You discuss everything about Company 1, then everything about Company 2, and then everything about Company 3. Or you discuss the management structure of Company 1, of Company 2, and of Company 3; then you address the engineering expertise of Company 1, of Company 2, and of Company 3; and so forth. |

| Assign items to logical categories or discuss the elements that make up a single item | Classification or partition. Classification involves placing items into categories according to some criterion. Partition involves breaking a single item or a group of items into major elements. | For classification, you group the motors your company manufactures according to the fuel they burn: gasoline or diesel. For partition, you explain the operation of each major component of one of your motors. |

| Discuss a problem you encountered, the steps you took to address the problem, and the outcome or solution | Problem-methods-solution. You can use this pattern in discussing the past, the present, or the future. Readers understand this organizational pattern because they use it in their everyday lives. | In describing how your company is responding to a new competitor, you discuss the problem (the recent loss in sales), the methods (how you plan to examine your product line and business practices), and the solution (which changes will help your company prosper). |

| Discuss the factors that led to (or will lead to) a given situation, or the effects that a situation led to or will lead to | Cause and effect. You can start from causes and speculate about effects, or you can start with the effect and try to determine which factors were the causes of that effect. | You discuss factors that you think contributed to a recent sales dip for one of your products. Or you explain how you think changes to an existing product will affect its future sales. |

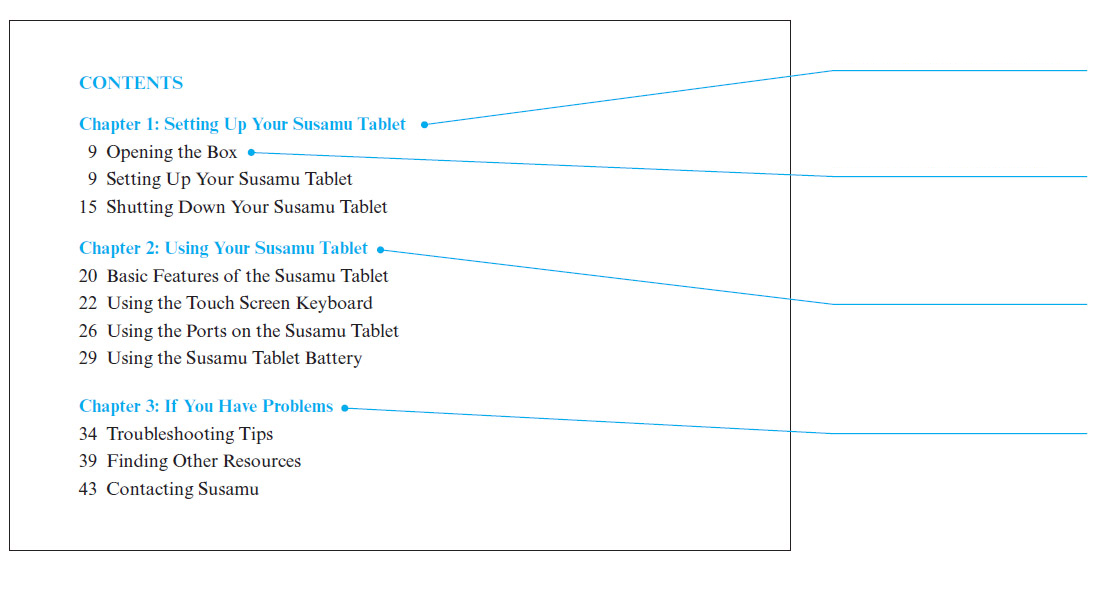

Long, complex arguments often require several organizational patterns. For instance, one part of a document might be a causal analysis of the problem you are writing about, and another might be a comparison and contrast of two options for solving that problem. Figure 7.1, an excerpt from a user’s manual, shows how different patterns might be used in a single document.

Different sections of this manual use different organizational patterns.

Chapter 1 is organized chronologically: you take the product out of the box before you set it up and run it and before you shut it down.

In Chapter 1, the section called “Opening the Box” uses partition by showing and naming the various items that are included in the package.

Chapter 2 is organized from general to specific: you want to understand the basic features of the product before you study the more specialized features.

Chapter 3 is organized according to the problem-methods-solution pattern. The reader tries to solve the problem by reading the troubleshooting tips, locating other resources, and contacting the manufacturer.

Figure 7.1 Using Multiple Organizational Patterns in a Single Document

The chronological—or timeline—pattern is commonly used to describe events. In an accident report, you describe the events in the order in which they occurred. In the background section of a report, you describe the events that led to the present situation. In a set of slides for an oral presentation, you explain the role of social media in U.S. presidential elections by discussing each of the presidential elections, in order, since 2000.

Organizing Information Chronologically

These three suggestions can help you write an effective chronological passage.

- Provide signposts. If the passage is more than a few hundred words long, use headings. Choose words such as step, phase, stage, and part, and consider numbering them. Add descriptive phrases to focus readers’ attention on the topic of the section:

Phase One: Determining Our Objectives

Step 3: Installing the Lateral Supports

At the paragraph and sentence levels, transitional words such as then, next, first, and finally will help your reader follow your discussion.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Flowcharts, in particular, help you emphasize chronological passages for all kinds of readers, from the most expert to the general reader.

- Analyze events where appropriate. When you use chronology, you are explaining what happened in what sequence, but you are not necessarily explaining why or how an event occurred or what it means. For instance, the largest section of an accident report is usually devoted to the chronological discussion, but the report is of little value unless it explains what caused the accident, who bears responsibility, and how such accidents can be prevented.

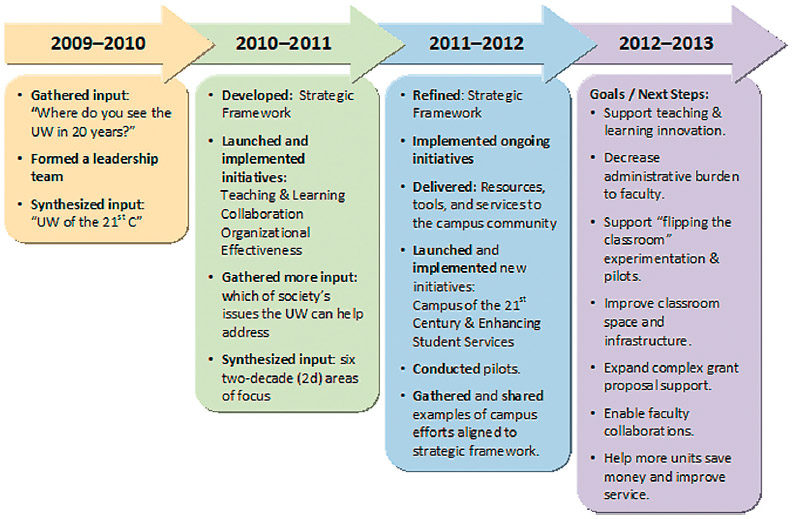

Figure 7.2, a timeline presented on the University of Washington’s website, is organized chronologically.

The university wishes to organize its academic initiative chronologically: in terms of academic-year periods. Therefore, it makes sense to use a timeline with a list of the activities that will occur in each period. The different color for each period further emphasizes the role of chronology.

Figure 7.2 Information Organized Chronologically

The spatial pattern is commonly used to describe objects and physical sites. In an accident report, you describe the physical scene of the accident. In a feasibility study about building a facility, you describe the property on which it would be built. In a proposal to design a new microchip, you describe the layout of the new chip.

Organizing Information Spatially

These three suggestions can help you write an effective spatial passage.

- Provide signposts. Help your readers follow the argument by using words and phrases that indicate location (to the left, above, in the center) in headings, topic sentences, and support sentences.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Diagrams, drawings, photographs, and maps clarify spatial relationships.

- Analyze events where appropriate. A spatial arrangement doesn't explain itself; you have to do the analysis. A diagram of a floor plan cannot explain why the floor plan is effective or ineffective.

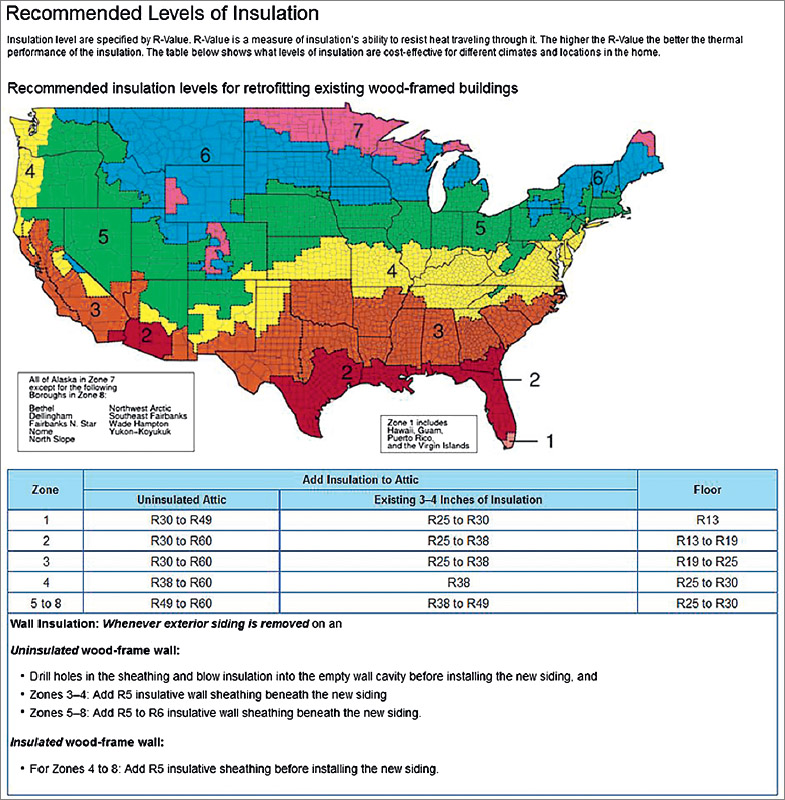

Figure 7.3 shows the use of spatial organization.

This information is addressed to homeowners who want to add insulation to their attics or floors. To help readers understand how much insulation they need based on their climate, the writers could have used an alphabetical list of cities or states or zip codes. Instead, the writers chose a map because it enables readers to quickly and easily “see” the climate in their region.

Figure 7.3 Information Organized Spatially

The general-to-specific pattern is useful when your readers need a general understanding of a subject to help them understand and remember the details. For example, in a report, you include an executive summary—an overview for managers—before the body of the report. In a set of instructions, you provide general information about the necessary tools and materials and about safety measures before presenting the step-by-step instructions. In a blog, you describe the topic of the blog before presenting the individual blog posts.

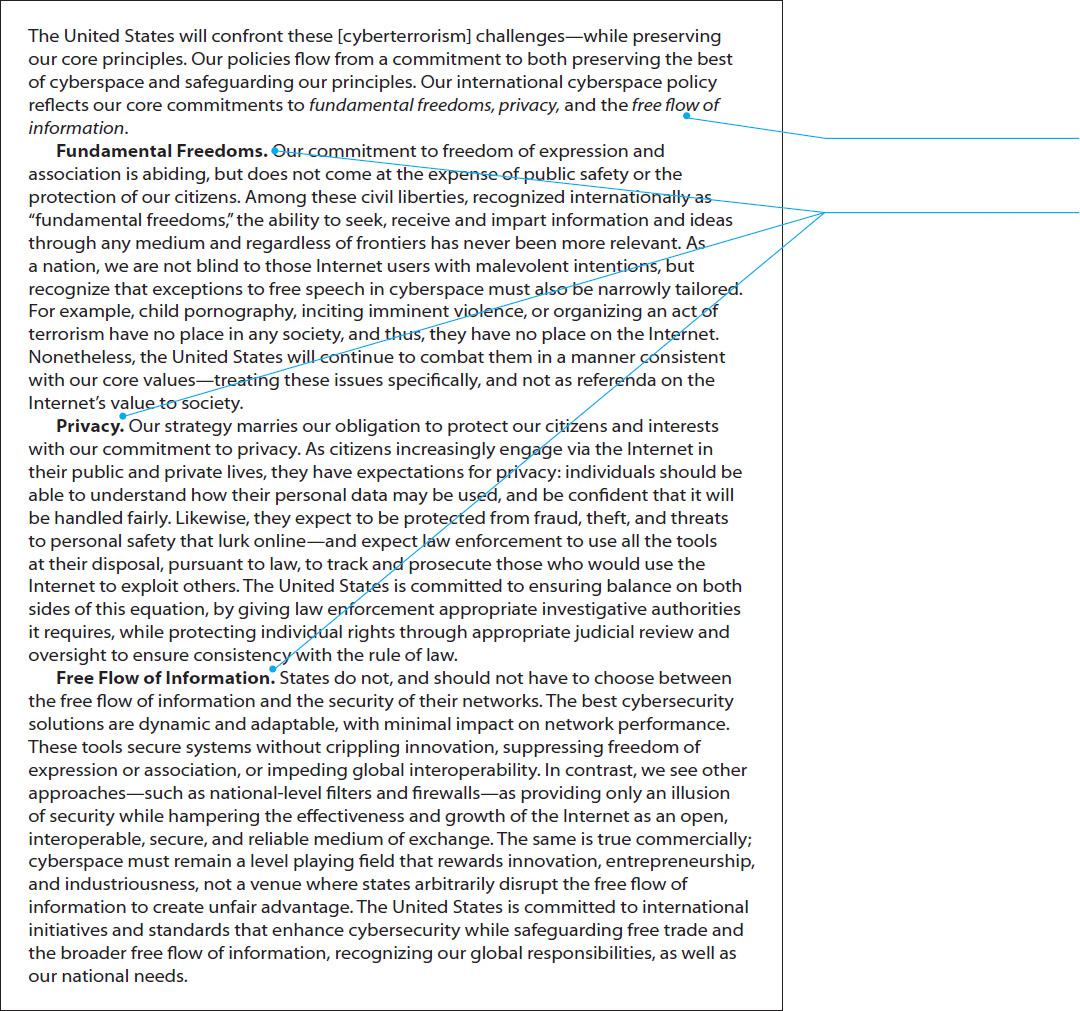

Figure 7.4, from the U.S. Department of State, explains the principles underlying the nation’s cybersecurity policy.

The first paragraph is an advance organizer: a general summary of the topics that will be addressed in more detail.

The three topics are announced in the italicized phrases.

These phrases are used at the start of the three sections.

Figure 7.4 Information Organized from General to Specific

Organizing Information from General to Specific

These two suggestions can help you use the general-to-specific pattern effectively.

- Provide signposts. Explain that you will address general issues first and then move on to specific concerns. If appropriate, incorporate the words general and specific or other relevant terms in the major headings or at the start of the text for each item you describe.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Diagrams, drawings, photographs, and maps help your reader understand both the general information and the fine points.

The more-important-to-less-important organizational pattern recognizes that readers often want the bottom line—the most-important information—first. For example, in an accident report, you describe the three most important factors that led to the accident before describing the less-important factors. In a feasibility study about building a facility, you present the major reasons that the proposed site is appropriate, then the minor reasons. In a proposal to design a new microchip, you describe the major applications for the new chip, then the minor applications.

For most documents, this pattern works well because readers want to get to the bottom line as soon as possible. For some documents, however, other patterns work better. People who write for readers outside their own company often reverse the more-important-to-less-important pattern because they want to make sure their audience reads the whole discussion. This reversed pattern is also popular with writers who are delivering bad news. For instance, if you want to justify recommending that your organization not go ahead with a popular plan, the reverse sequence lets you explain the problems with the popular plan before you present the plan you recommend. Otherwise, readers might start to formulate objections before you have had a chance to explain your position.

Organizing Information from More Important to Less Important

These three suggestions can help you write a passage organized from more important to less important.

- Provide signposts. Tell your readers how you are organizing the passage. For instance, in the introduction of a proposal to design a new microchip, you might write, “The three applications for the new chip, each of which is discussed below, are arranged from most important to least important.”

In creating signposts, be straightforward. If you have two very-important points and three less-important points, present them that way: group the two important points and label them something like “Major Reasons to Retain Our Current Management Structure.” Then present the less-important factors as “Other Reasons to Retain Our Current Management Structure.” Being straightforward makes the material easier to follow and enhances your credibility.

- Explain why one point is more important than another. Don’t just say that you will be arranging the items from more important to less important. Explain why the more-important point is more important.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Diagrams and numbered lists often help to suggest levels of importance.

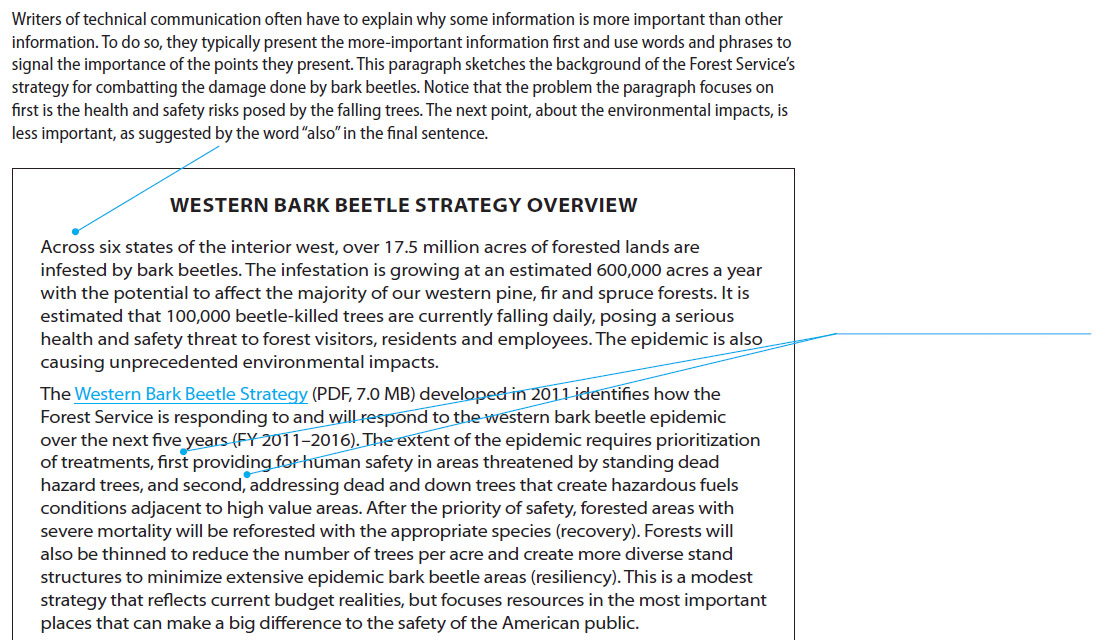

Figure 7.5, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, shows the more-important-to-less-important organizational structure.

Here the writer uses the words “first” and “second” to signal priority. Safety is the most important issue; reforestation is less important, as suggested by the phrase “After the priority of safety.” Thinning the forests is a lower priority, as suggested by the word “also” in the phrase “Forests will also be thinned.”

Figure 7.5 Information Organized from More Important to Less Important

Typically, the comparison-and-contrast pattern is used to describe and evaluate two or more items or options. For example, in a memo, you compare and contrast the credentials of three finalists for a job. In a proposal to design a new microchip, you compare and contrast two different strategies for designing the chip. In a video explaining different types of low-emissions vehicles, you compare and contrast electric cars and hybrids.

The first step in comparing and contrasting two or more items is to determine the criteria: the standards or needs you will use in studying the items. For example, if a professional musician who plays the piano in restaurants was looking to buy a new portable keyboard, she might compare and contrast available instruments using the number of keys as one criterion. For this person, 88 keys would be better than 64. Another criterion might be weight: lighter is better than heavier.

Almost always, you will need to consider several or even many criteria. Start by deciding whether each criterion represents a necessary quality or merely a desirable one. In studying keyboards, for instance, the number of keys might be a necessary quality. If you need an 88-key instrument to play your music, you won’t consider any instruments without 88 keys. The same thing might be true of touch-sensitive keys. But a MIDI interface might be less important, a merely desirable quality; you would like MIDI capability, but you would not eliminate an instrument from consideration just because it doesn’t have MIDI.

Two typical patterns for organizing a comparison-and-contrast discussion are whole-by-whole and part-by-part. The following example illustrates the difference between them. The example shows how two printers—Model 5L and Model 6L—might be compared and contrasted according to three criteria: price, resolution, and print speed.

The whole-by-whole pattern provides a coherent picture of each option: Model 5L and Model 6L. This pattern works best if your readers need an overall assessment of each option or if each option is roughly equivalent according to the criteria.

The part-by-part pattern lets you focus your attention on the criteria. If, for instance, Model 5L produces much better resolution than Model 6L, the part-by-part pattern reveals this difference more effectively than the whole-by-whole pattern does. The part-by-part pattern is best for detailed comparisons and contrasts.

| Whole-by-whole | Part-by-part |

Model 5L

|

Price

|

Organizing Information by Comparison and Contrast

These four suggestions can help you compare and contrast items effectively.

- Establish criteria for the comparison and contrast. Choose criteria that are consistent with the needs of your audience.

- Evaluate each item according to the criteria you have established. Draw your conclusions.

- Organize the discussion. Choose either the whole-by-whole or the part-by-part pattern or some combination of the two. Then order the second-level items.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Graphics can clarify and emphasize comparison-and-contrast passages. Diagrams, drawings, and tables are common ways to provide such clarification and emphasis.

You can have it both ways. You can begin with a general description of the various items and then use a part-by-part pattern to emphasize particular aspects.

Once you have chosen the overall pattern—whole-by-whole or part-by-part—you decide how to order the second-level items. That is, in a whole-by-whole passage, you have to sequence the aspects of the items or options being compared; in a part-by-part passage, you have to sequence the items or options themselves.

ETHICS NOTE: COMPARING AND CONTRASTING FAIRLY

Because the comparison-and-contrast organizational pattern is used frequently in evaluating items, it appears often in product descriptions as part of the argument that one company’s products are better than a competitor’s. There is nothing unethical in this. But it is unethical to misrepresent items, such as when writers portray their own product as better than it is or portray their competitor’s as worse than it is.

Obviously, lying about a product is unethical. But some practices are not so easy to characterize. For example, suppose your company makes tablet computers and your chief competitor’s model has a longer battery life than yours. In comparing and contrasting the two tablets, are you ethically obligated to mention battery life? No, you are not. If readers are interested in battery life, it is their responsibility to figure out what your failure to mention battery life means and seek further information from other sources. If you do mention battery life, however, you must do so honestly, using industry-standard techniques for measuring it. You cannot measure your tablet’s battery life under one set of conditions and your competitor’s under another set.

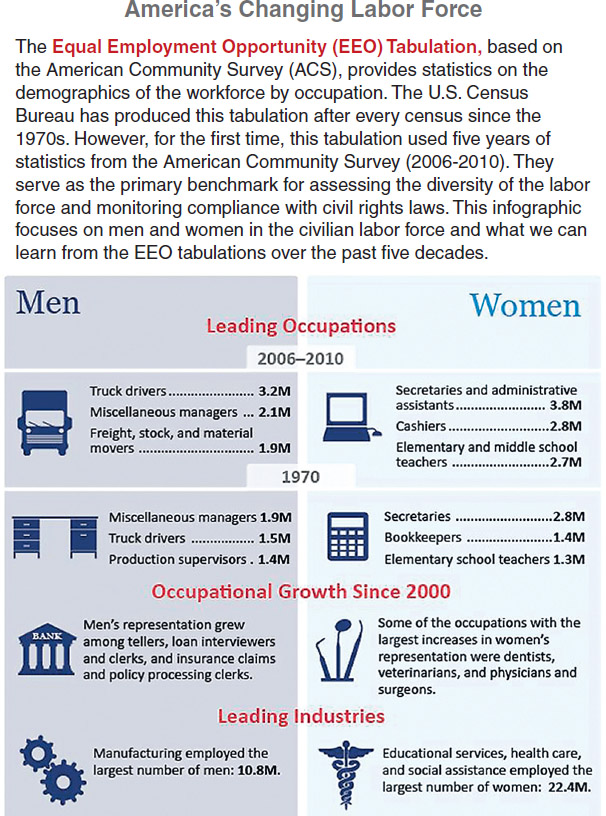

Figure 7.6 shows a comparison-and-contrast table about employment in the labor force.

This excerpt from an infographic published by the federal government presents a lot of information about employment in the civilian labor force in the United States, now and in 1970. The main theme is the comparison between men and women: how many are in the workforce and what jobs they hold or held. Because the main basis of comparison and contrast is the sex of workers, the writers chose a basic table structure, with data about men in one column and data about women in the other.

Figure 7.6 Information Organized by Comparison and Contrast

Classification is the process of assigning items to categories. For instance, all the students at a university could be classified by sex, age, major, and many other characteristics. You can also create subcategories within categories, such as males and females majoring in business.

Classification is common in technical communication. In a feasibility study about building a facility, you classify sites into two categories: domestic or foreign. In a journal article about ways to treat a medical condition, you classify the treatments as surgical or nonsurgical. In a description of a major in a college catalog, you classify courses as required or elective.

Partition is the process of breaking a unit into its components. For example, a home-theater system could be partitioned into the following components: TV, amplifier, peripheral devices such as DVD players, and speakers. Each component is separate, but together they form a whole system. Each component can, of course, be partitioned further.

Partition is used in descriptions of objects, mechanisms, and processes. In an equipment catalog, you use partition to describe the major components of one of your products. In a proposal, you use partition to present a detailed description of an instrument you propose to develop. In a brochure, you explain how to operate a product by describing each of its features.

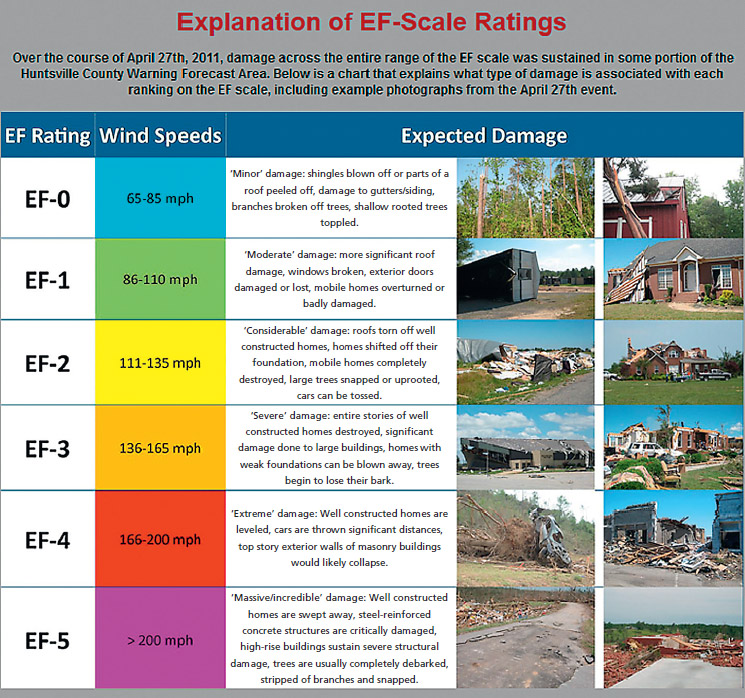

In Figure 7.7, the writer uses classification effectively in introducing categories of tornados to a general audience.

Figure 7.7 Information Organized by Classification

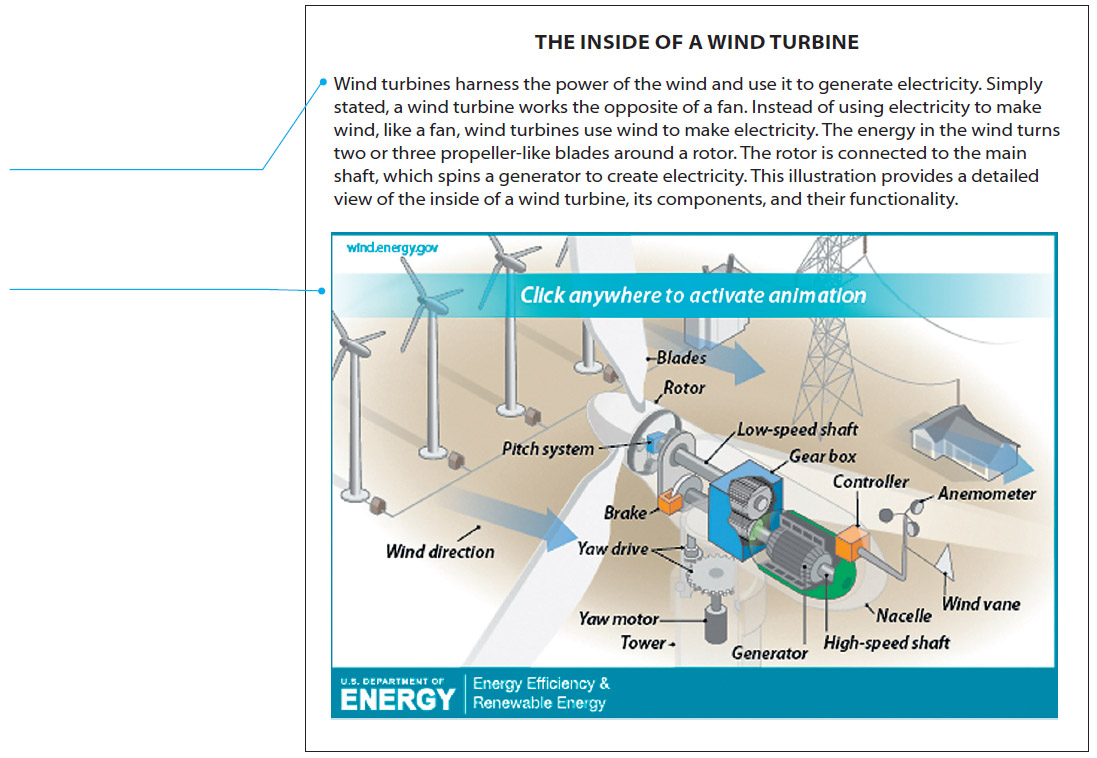

Figure 7.8 illustrates partition. Read more examples of partition in Chapter 20, which includes descriptions of objects, mechanisms, and processes.

This example of partition begins with a textual overview of the topic.

This interactive graphic enables the reader to see the components of the wind turbine in operation as the equipment generates electricity.

Following this graphic is a description of each of the components shown in the graphic.

Figure 7.8 Information Organized By Partition

Organizing Information by Classification or Partition

These six suggestions can help you write an effective classification or partition passage.

- Choose a basis of classification or partition that fits your audience and purpose. If you are writing a warning about snakes for hikers in a particular state park, your basis of classification will probably be whether the snakes are poisonous. You will describe all the poisonous snakes, then all the nonpoisonous ones.

- Use only one basis of classification or partition at a time. If you are classifying graphics programs according to their technology—paint programs and draw programs—do not include another basis of classification, such as cost.

- Avoid overlap. In classifying, make sure that no single item could logically be placed in more than one category. In partitioning, make sure that no listed component includes another listed component. Overlapping generally occurs when you change the basis of classification or the level at which you are partitioning a unit. In the following classification of bicycles, for instance, the writer introduces a new basis of classification that results in overlapping categories:

—mountain bikes

—racing bikes

—comfort bikes

—ten-speed bikes

The first three items share a basis of classification: the general category of bicycle. The fourth item has a different basis of classification: number of speeds. Adding the fourth item is illogical because a particular ten-speed bike could be a mountain bike, a racing bike, or a comfort bike.

- Be inclusive. Include all the categories necessary to complete your basis of classification. For example, a partition of an automobile by major systems would be incomplete if it included the electrical, fuel, and drive systems but not the cooling system. If you decide to omit a category, explain why.

- Arrange the categories in a logical sequence. Use a reasonable plan, such as chronology (first to last), spatial development (top to bottom), or importance (most important to least important).

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Organization charts are commonly used in classification passages; drawings and diagrams are often used in partition passages.

The problem-methods-solution pattern reflects the logic used in carrying out a project. The three components of this pattern are simple to identify:

- Problem. A description of what was not working (or not working effectively) or what opportunity exists for improving current processes.

- Methods. The procedures performed to confirm the analysis of the problem, solve the problem, or exploit the opportunity.

- Solution. The statement of whether the analysis of the problem was correct or of what was discovered or devised to solve the problem or capitalize on the opportunity.

The problem-methods-solution pattern is common in technical communication. In a proposal, you describe a problem in your business, how you plan to carry out your research, and how your deliverable (an item or a report) can help solve the problem. In a completion report about a project to improve a manufacturing process, you describe the problem that motivated the project, the methods you used to carry out the project, and the findings: the results, conclusions, and recommendations.

Organizing Information by Problem-Methods-Solution

These five suggestions can help you write an effective problem-methods-solution passage.

- In describing the problem, be clear and specific. Don’t write, “Our energy expenditures are getting out of hand.” Instead, write, “Our energy usage has increased 7 percent in the last year, while utility rates have risen 11 percent.” Then calculate the total increase in energy costs.

- In describing your methods, help your readers understand what you did and why you did it that way. You might need to justify your choices. Why, for example, did you use a t-test in calculating the statistics in an experiment? If you can’t defend your choice, you lose credibility.

- In describing the solution, don’t overstate. Avoid overly optimistic claims, such as “This project will increase our market share from 7 percent to 10 percent within 12 months.” Instead, be cautious: “This project could increase our market share from 7 percent to 10 percent.” This way, you won’t be embarrassed if things don’t turn out as well as you had hoped.

- Choose a logical sequence. The most common sequence is to start with the problem and conclude with the solution. However, different sequences work equally well as long as you provide a preliminary summary to give readers an overview and include headings or some other design elements to help readers find the information they want (see Chapter 11). For instance, you might want to put the methods last if you think your readers already know them or are more interested in the solution.

- Consider using graphics to complement the text. Graphics, such as flowcharts, diagrams, and drawings, can clarify problem-methods-solution passages.

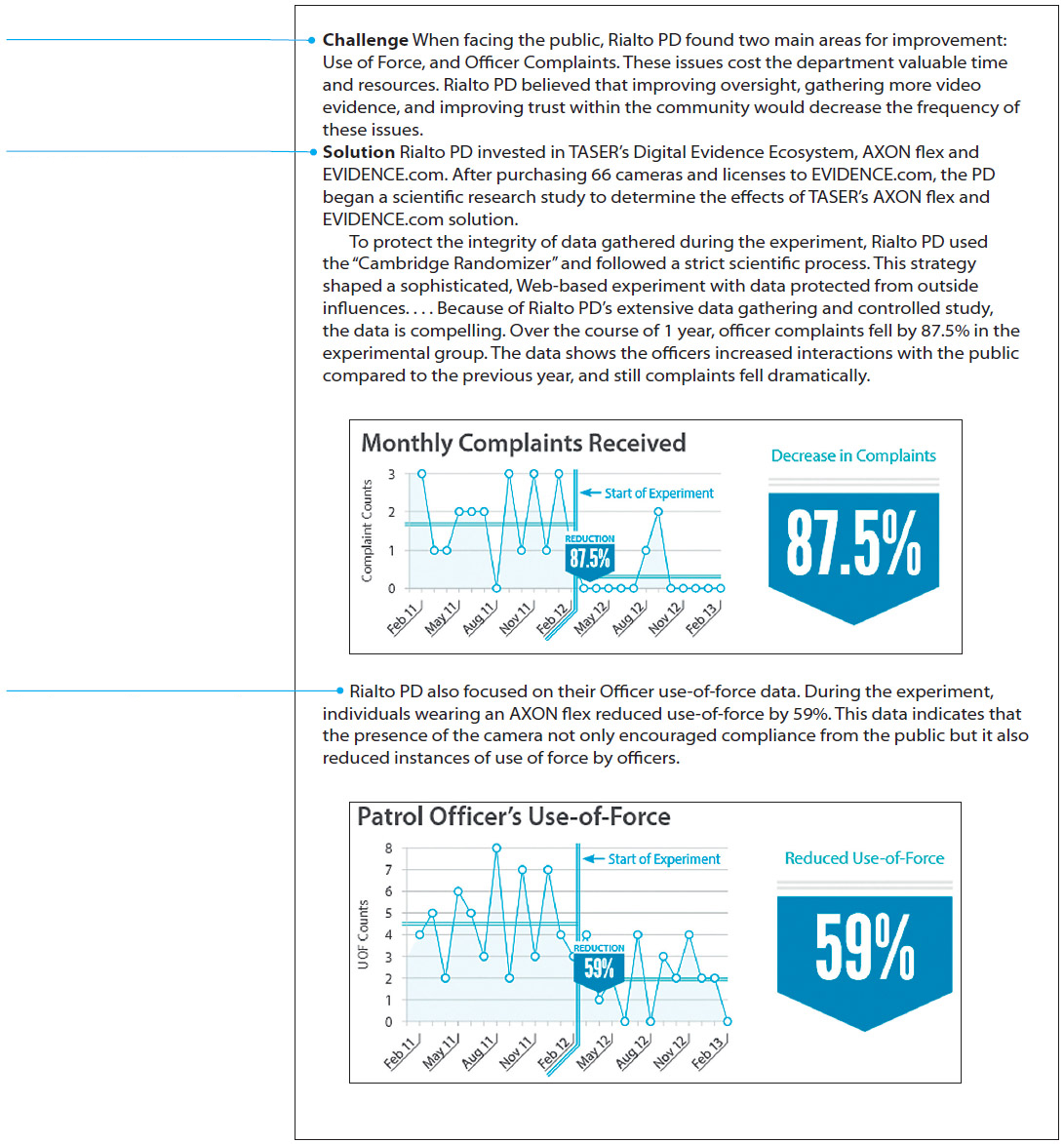

Figure 7.9 shows the problem-methods-solution pattern. The passage is from a case study of a police department using TASER equipment to solve two problems.

“Challenge” presents the problem at the Rialto, California, police department.

“Solution” begins with a discussion of the methods the police department took to solve the two problems.

Note that writers do not necessarily use the words problem, methods, and solution in this method of organization. Don’t worry about the terminology; the important point is to recognize that this organizational pattern is based on identifying a problem, doing something to respond to it, and thereby reducing or solving it.

Figure 7.9 Information Organized by the Problem-Methods-Solution Pattern

Technical communication often involves cause-and-effect discussions. Sometimes you will reason forward, from cause to effect: if we raise the price of a particular product we manufacture (cause), what will happen to our sales (effect)? Sometimes you will reason backward, from effect to cause: productivity went down by 6 percent in the last quarter (effect); what factors led to this decrease (causes)? Cause-and-effect reasoning, therefore, provides a way to answer the following two questions:

- What will be the effect(s) of X?

- What caused X?

Arguments organized by cause and effect appear in various types of technical communication. In an environmental impact statement, you argue that a proposed construction project would have three important effects on the ecosystem. In the recommendation section of a report, you argue that a recommended solution would improve operations in two major ways. In a memo, you describe a new policy and then explain the effects you anticipate the policy will have.

Cause-and-effect relationships are difficult to describe because there is no scientific way to determine causes or effects. You draw on your common sense and your knowledge of your subject. When you try to determine, for example, why the product your company introduced last year sold poorly, you start with the obvious possibilities: the market was saturated, the product was of low quality, the product was poorly marketed, and so forth. The more you know about your subject, the more precise and insightful your analysis will be.

But a causal discussion can never be certain. You cannot prove why a product failed in the marketplace; you can only explain why the factors you are identifying are the most plausible causes or effects. For instance, to make a plausible case that the main reason for the product’s weak performance is that it was poorly marketed, you can show that, in the past, your company’s other unsuccessful products were marketed in similar ways and your company’s successful products were marketed in other ways.

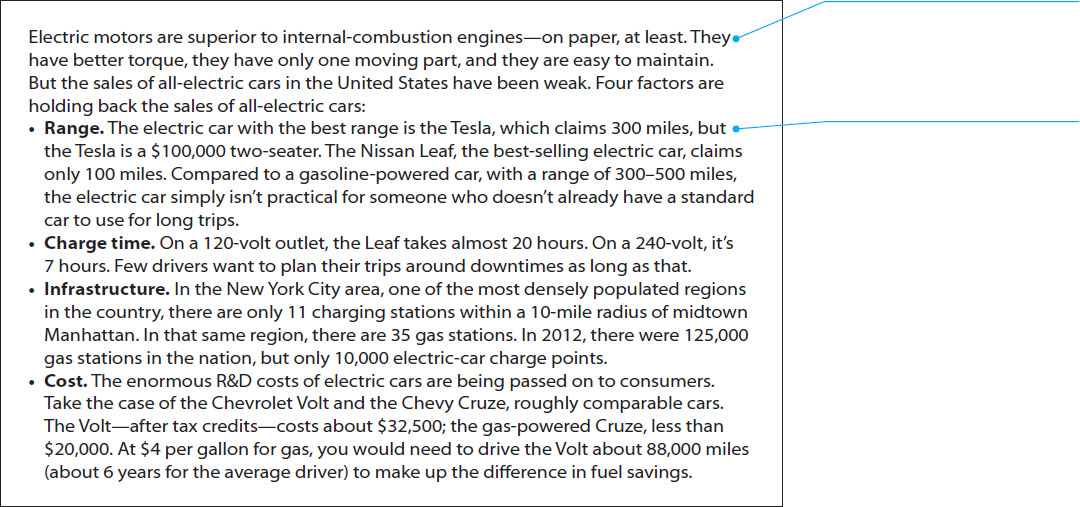

Figure 7.10 illustrates an effective cause-and-effect argument. The writer is explaining why electric vehicles have not sold well in the United States.

The first paragraph presents the effect in this cause-effect argument: electric cars are not popular in the United States.

The bullet list presents four causes.

Figure 7.10 A Discussion Organized by the Cause-and-Effect Pattern

Organizing Information by Cause and Effect

These four suggestions can help you write an effective cause-and-effect passage.

Explain your reasoning. To support your claim that the product was marketed poorly, use specific facts and figures: the low marketing budget, delays in beginning the marketing campaign, and so forth.

Explain your reasoning. To support your claim that the product was marketed poorly, use specific facts and figures: the low marketing budget, delays in beginning the marketing campaign, and so forth.

Avoid overstating your argument. For instance, if you write that Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, “created the computer revolution,” you are claiming too much. It is better to write that Gates “was one of the central players in creating the computer revolution.”

Avoid overstating your argument. For instance, if you write that Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, “created the computer revolution,” you are claiming too much. It is better to write that Gates “was one of the central players in creating the computer revolution.”

Avoid logical fallacies. Logical fallacies, such as hasty generalizations or post hoc reasoning, can also undermine your discussion.

Avoid logical fallacies. Logical fallacies, such as hasty generalizations or post hoc reasoning, can also undermine your discussion.

Consider using graphics to complement the text. Graphics, such as flowcharts, organization charts, diagrams, and drawings, can clarify and emphasize cause-and-effect passages.

Consider using graphics to complement the text. Graphics, such as flowcharts, organization charts, diagrams, and drawings, can clarify and emphasize cause-and-effect passages.