Your Legal Obligations

Printed Page 24-29

Your Legal Obligations

Although most people believe that ethical obligations are more comprehensive and more important than legal obligations, the two sets of obligations are closely related. Our ethical values have shaped many of our laws. For this reason, professionals should know the basics of four different bodies of law: copyright, trademark, contract, and liability.

COPYRIGHT LAW

As a student, you are frequently reminded to avoid plagiarism. A student caught plagiarizing would likely fail the assignment and possibly the course and might even be expelled from school. A medical researcher or a reporter caught plagiarizing would likely be fired or at least find it difficult to publish in the future. But plagiarism is an ethical, not a legal, issue. Although a plagiarist might be expelled from school or be fired, he or she will not be fined or sent to prison.

By contrast, copyright is a legal issue. Copyright law is the body of law that relates to the appropriate use of a person’s intellectual property: written documents, pictures, musical compositions, and the like. Copyright literally refers to a person’s right to copy the work that he or she has created.

The most important concept in copyright law is that only the copyright holder—the person or organization that owns the work—can copy it. For instance, if you work for Zipcar, you can legally copy information from the Zipcar website and use it in other Zipcar documents. This reuse of information is routine in business, industry, and government because it helps ensure that the information a company distributes is both consistent and accurate.

However, if you work for Zipcar, you cannot simply copy information that you find on the Car2Go website and put it in Zipcar publications. Unless you obtained written permission from Car2Go to use its intellectual property, you would be infringing on Car2Go’s copyright.

Why doesn’t the Zipcar employee who writes the information for Zipcar own the copyright to that information? The answer lies in a legal concept known as work made for hire. Anything written or revised by an employee on the job is the company’s property, not the employee’s.

Although copyright gives the owner of the intellectual property some rights, it doesn’t give the owner all rights. You can place small portions of copyrighted text in your own document without getting formal permission from the copyright holder. When you quote a few lines from an article, for example, you are taking advantage of a part of copyright law called fair use. Under fair-use guidelines, you have the right to use a portion of a published work, without getting permission, for purposes such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Because fair use is based on a set of general guidelines that are meant to be interpreted on a case-by-case basis, you should still cite the source accurately to avoid potential plagiarism.

Determining Fair Use

Courts consider four factors in disputes over fair use:

- The purpose and character of the use, especially whether the use is for profit. Profit-making organizations are scrutinized more carefully than nonprofits.

- The nature and purpose of the copyrighted work. When the information is essential to the public—for example, medical information—the fair-use principle is applied more liberally.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion of the work used. A 200-word passage would be a small portion of a book but a large portion of a 500-word brochure.

- The effect of the use on the potential market for the copyrighted work. Any use of the work that is likely to hurt the author’s potential to profit from the original work would probably not be considered fair use.

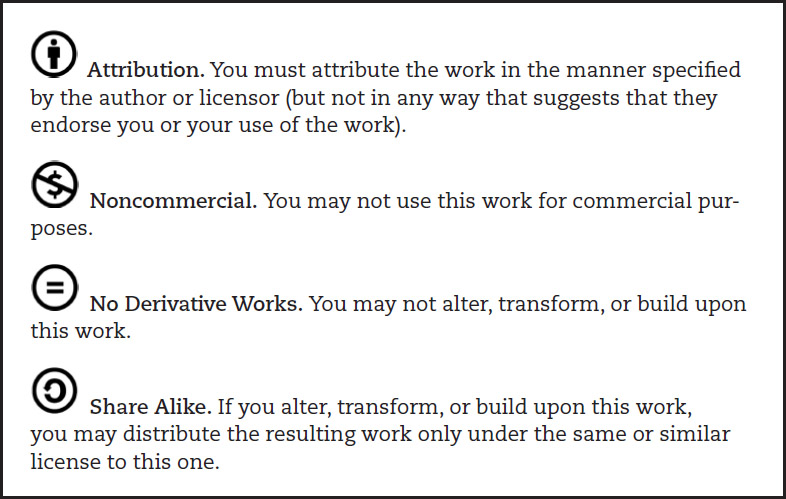

A new trend is for copyright owners to stipulate which rights they wish to retain and which they wish to give up. You might see references to Creative Commons, a not-for-profit organization that provides symbols for copyright owners to use to communicate their preferences. Figure 2.1 shows four of the Creative Commons symbols.

Dealing with Copyright Questions

Consider the following advice when using material from another source.

- Abide by the fair-use concept. Do not rely on excessive amounts of another source’s work (unless the information is your company’s own boilerplate).

- Seek permission. Write to the source, stating what portion of the work you wish to use and the publication you wish to use it in. The source is likely to charge you for permission.

- Cite your sources accurately. Citing sources fulfills your ethical obligation and strengthens your writing by showing the reader the range of your research.

- Consult legal counsel if you have questions. Copyright law is complex. Don’t rely on instinct or common sense.

ETHICS NOTE

DISTINGUISHING PLAGIARISM FROM ACCEPTABLE REUSE OF INFORMATION

Plagiarism is the act of using someone else’s words or ideas without giving credit to the original author. It doesn’t matter whether the writer intended to plagiarize. Obviously, it is plagiarism to borrow or steal graphics, video or audio media, written passages, or entire documents and then use them without attribution. Web-based sources are particularly vulnerable to plagiarism, partly because people mistakenly think that if information is on the web it is free to borrow and partly because this material is so easy to copy, paste, and reformat.

However, writers within a company often reuse one another’s information without giving credit—and it is completely ethical. For instance, companies publish press releases when they wish to publicize news. These press releases typically conclude with descriptions of the company and how to get in touch with an employee who can answer questions about the company’s products or services. These descriptions, sometimes called boilerplate, are simply copied and pasted from previous press releases. Because these descriptions are legally the intellectual property of the company, reusing them in this way is completely honest. Similarly, companies often repurpose their writing. That is, they copy a description of the company from a press release and paste it into a proposal or an annual report. This reuse also is acceptable.

When you are writing a document and need a passage that you suspect someone in your organization might already have written, ask a more-experienced co-worker whether the culture of your organization permits reusing someone else’s writing. If the answer is yes, check with your supervisor to see whether he or she approves of what you plan to do.

Companies use trademarks and registered trademarks to ensure that the public recognizes the name or logo of a product.

- A trademark is a word, phrase, name, or symbol that is identified with a company. The company uses the TM symbol after the product name to claim the design or device as a trademark. However, using this symbol does not grant the company any legal rights. It simply sends a message to other organizations that the company is claiming a trademark.

- A registered trademark is a word, phrase, name, or symbol that the company has registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The company can then use the ® symbol after the trademarked item. Registering a trademark, a process that can take years, ensures much more legal protection than a simple trademark throughout the United States, as well as in other nations. Although a company is not required to use the symbol, doing so makes it easier to take legal action against another organization that it believes has infringed on its trademark.

All employees are responsible for using trademark and registered trademark symbols accurately when referring to a company’s products.

Protecting Trademarks

Use the following techniques to protect your client’s or employer’s trademark.

- Distinguish trademarks from other material. Use boldface, italics, a different typeface, a different type size, or a different color to distinguish the trademarked item.

- Use the trademark symbol. At least once in each document—preferably the first time the name or logo appears—use the appropriate symbol after the name or logo, followed by an asterisk. At the bottom of the page, include a statement such as the following: “*COKE is a registered trademark of the Coca-Cola Company.”

- Use the trademarked item’s name as an adjective, not as a noun or verb. Trademarks can become confused with the generic term they refer to. Use the trademarked name along with the generic term, as in Xerox® photocopier or LaserJet® printer.

DOES NOT PROTECT TRADEMARK buy three LaserJets® PROTECTS TRADEMARK buy three LaserJet® printers - Do not use the possessive form of the trademarked name. Doing so reduces the uniqueness of the item and encourages the public to think of the term as generic.

DOES NOT PROTECT TRADEMARK iPad’s® fine quality PROTECTS TRADEMARK the fine quality of iPad® tablets

CONTRACT LAW

Contract law deals with agreements between two parties. In most cases, disputes concern whether a product lives up to the manufacturer’s claims. These claims take the form of express warranties or implied warranties.

An express warranty is a written or oral statement that the product has a particular feature or can perform a particular function. For example, a statement in a printer manual that the printer produces 17 pages per minute is an express warranty. An implied warranty is one of two kinds of non-written guarantees:

- The merchantability warranty guarantees that the product is of at least average quality and appropriate for the ordinary purposes it was intended to serve.

- The fitness warranty guarantees that the product is suitable for the buyer’s purpose if the seller knows that purpose. For example, if a car salesperson knows that a buyer wishes to pull a 5,000-pound trailer but also knows that a car cannot pull such a load, the salesperson is required to inform the buyer of this fact.

LIABILITY LAW

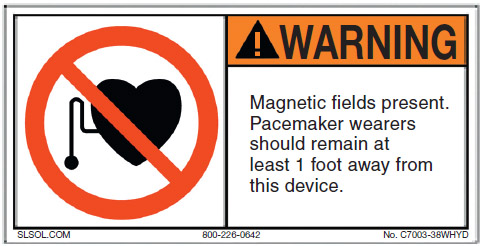

Under product-liability law, a manufacturer or seller of a product is liable for injuries or damages caused by the use of that product. Liability is an important concern for communicators, because courts frequently rule that manufacturers are responsible for providing adequate operating instructions and for warning consumers about the risks of using their products. Figure 2.2 shows a warning label used to inform people of how to avoid a safety risk.

Manufacturers of products used in the United States have a legal duty to warn users by providing safety labels on products (and the same information in their accompanying instructions) and by explaining in the instructions how to use the products safely. According to intellectual-property attorney Kenneth Ross (2011), the manufacturer has this duty to warn when all four of these characteristics apply:

- The product is dangerous.

- The danger is or should be known by the manufacturer.

- The danger is present when the product is used in the usual and expected manner.

- The danger is not obvious to or well known by the user.

The complication for technical communicators is that one set of guidelines regarding duty to warn is used in the United States (the American National Standards Institute’s ANSI Z535, last revised in 2011) and another set is used in the European Union (the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 3864, which is updated periodically). Both sets of guidelines are relatively vague, and they contradict each other in important ways. Therefore, before publishing labels or instructions for products that can be dangerous, consult with an attorney who specializes in liability issues.

Abiding by Liability Laws

Pamela S. Helyar summarizes the communicator’s obligations and offers ten guidelines for abiding by liability laws (1992):

- Understand the product and its likely users. Learn everything you can about the product and its users.

- Describe the product’s functions and limitations. Help people determine whether it is the right product to buy. In one case, a manufacturer was found liable for not stating that its electric smoke alarm does not work during a power outage.

- Instruct users on all aspects of ownership. Include assembly, installation, use and storage, testing, maintenance, first aid and emergencies, and disposal.

- Use appropriate words and graphics. Use common terms, simple sentences, and brief paragraphs. Structure the document logically, and include specific directions. Make graphics clear and easy to understand; where necessary, show people performing tasks. Make the words and graphics appropriate to the educational level, mechanical ability, manual dexterity, and intelligence of intended users. For products that will be used by children or nonnative speakers of your language, include graphics illustrating important information.

- Warn users about the risks of using or misusing the product. Warn users about the dangers of using the product, such as chemical poisoning. Describe the cause, extent, and seriousness of the danger. A car manufacturer was found liable for not having warned consumers that parking a car on grass, leaves, or other combustible material could cause a fire. For particularly dangerous products, explain the danger and how to avoid it, and then describe how to use the product safely. Use mandatory language, such as must and shall, rather than might, could, or should. Use the words warning and caution appropriately.

- Include warnings along with assertions of safety. When product information says that a product is safe, readers tend to pay less attention to warnings. Therefore, include detailed warnings to balance the safety claims.

- Make directions and warnings conspicuous. Safety information must be in large type and easily visible, appear in an appropriate location, and be durable enough to withstand ordinary use of the product.

- Make sure that the instructions comply with applicable company standards and local, state, and federal laws.

- Perform usability testing on the product (to make sure it is safe and easy to use) and on the instructions (to make sure they are accurate and easy to understand).

- Make sure users receive the information. If you discover a problem after the product has been shipped to retailers, tell users by direct mail or email, if possible, or newspaper and online advertising if not. Automobile-recall notices are one example of how manufacturers contact their users.