Planning

Printed Page 42-48

Planning

Planning, which can take more than a third of the total time spent on a writing project, is critically important for every document, from an email message to a book-length manual. Start by thinking about your audience, because you need to understand whom you are writing to before you can figure out what you need to say about your subject.

ANALYZING YOUR AUDIENCE

If you are lucky, you can talk with your audience before and during your work on the document. These conversations can help you learn what your readers already know, what they want to know, and how they would like the information presented. You can test out drafts, making changes as you go.

Even if you cannot consult your audience while writing the document, you still need to learn everything you can about your readers so that you can determine the best scope, organization, and style for your document. Then, for each of your most important readers, try to answer the following three questions:

- Who is your reader? Consider such factors as education, job experience and responsibilities, skill in reading English, cultural characteristics, and personal preferences.

- What are your reader’s attitudes and expectations? Consider the reader’s attitudes toward the topic and your message, as well as the reader’s expectations about the kind of document you will be presenting.

- Why and how will the reader use your document? Think about what readers will do with the document. This includes the physical environment in which they will use it, the techniques they will use in reading it, and the tasks they will carry out after they finish reading it.

ANALYZING YOUR PURPOSE

You cannot start to write until you can state the purpose (or purposes) of the document. Ask yourself these two questions:

- After your readers have read your document, what do you want them to know or do?

- What beliefs or attitudes do you want them to hold?

A statement of purpose might be as simple as this: “The purpose of this report is to recommend whether the company should adopt a health-promotion program.” Although the statement of purpose might not appear in this form in the final document, you want to state it clearly now to help you stay on track as you carry out the remaining steps.

CHOOSING YOUR WRITING TOOLS

To watch a tutorial on cross-platform word processing, go to Ch. 3 > Additional Resources > Tutorials: macmillanhighered.com/ launchpad/techcomm11e.

Writers have more tools available to them than ever before. You probably do most of your writing with commercial software such as Microsoft Office or open-source software such as Open Office, and you will likely continue to do much of your writing with these tools. Because of the rapid increase in the number and type of composition tools, however, knowing your options and choosing the one that best meets your needs can help you create a stronger document.

If you travel often or if many people in different locations will collaborate on a given document, you may find it useful to work with a cloud-based tool such as Google Drive. Specialized tools built for professional writers can be particularly useful for long, complicated projects that require heavy research; Scrivener, for example, lets you gather your research data in a single location and easily reorganize your document at the section or chapter level. Composition programs optimized for tablets, such as WritePad, convert handwriting into text, translate text into a number of languages, and feature cloud-based storage. Before you begin a big project, consider which type of writing tool will best meet your project’s needs.

GENERATING IDEAS ABOUT YOUR SUBJECT

Generating ideas is a way to start mapping out the information you will need to include in the document, deciding where to put it, and identifying additional information that may be required.

First, find out what you already know about the topic by using any of the techniques shown in Table 3.1.

| TABLE 3.1 Techniques for Generating Ideas About Your Topic | ||

| TECHNIQUE | EXPLANATION | EXAMPLE |

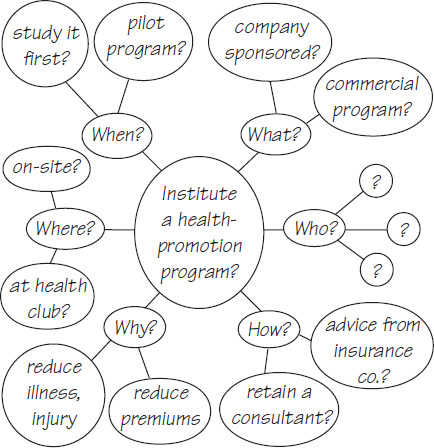

| Asking the six journalistic questions | Asking who, what, when, where, why, and how can help you figure out how much more research you need to do. Note that you can generate several questions from each of these six words. |

|

| Brainstorming | Spending 15 minutes listing short phrases and questions about your subject helps you think of related ideas. Later, when you construct an outline, you will rearrange your list, add new ideas, and toss out some old ones. |

|

| Freewriting | Writing without plans or restrictions, without stopping, can help you determine what you do and do not understand. And one phrase or sentence might spark an important idea. | A big trend today in business is sponsored health-promotion programs. Why should we do it? Many reasons, including boosting productivity and lowering our insurance premiums. But it’s complicated. One problem is that we can actually increase our risk if a person gets hurt. Another is the need to decide whether to have the program—what exactly is the program? . . . |

| Talking with someone | Discussing your topic can help you find out what you already know about it and generate new ideas. Simply have someone ask you questions as you speak. Soon you will find yourself in a conversation that will help you make new connections from one idea to another. | You: One reason we might want to do this is to boost productivity. Bob: What exactly are the statistics on increased productivity? And who has done the studies? Are they reputable? You: Good point. I’m going to have to show that putting money into a program is going to pay off. I need to see whether there are unbiased recent sources that present hard data. |

| Clustering | One way to expand on your topic is to write your main idea or main question in the middle of the page and then write second-level and third-level ideas around it. |

|

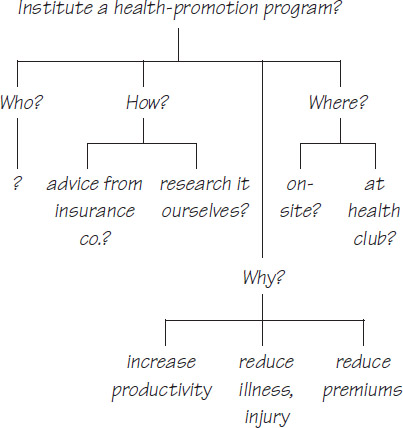

| Branching | Another way to help you expand on your topic is to write your main idea or question at the top of the page and then write second-level and third-level ideas below it. |

|

RESEARCHING ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Once you have a good idea of what you already know about your topic, you must obtain the rest of the information you will need. You can find and evaluate what other people have already written by reading reference books, scholarly books, articles, websites, and reputable blogs and discussion boards. In addition, you might compile new information by interviewing experts, distributing surveys and questionnaires, making observations, sending inquiries, and conducting experiments. Don’t forget to ask questions and gather opinions from your own network of associates, both inside and outside your organization.

ORGANIZING AND OUTLINING YOUR DOCUMENT

Although each document has its own requirements, you can use existing organizational patterns or adapt them to your own situation. For instance, the compare-and-contrast pattern might be an effective way to organize a discussion of different health-promotion programs. The cause-and-effect pattern might work well for a discussion of the effects of implementing such a program.

To watch a tutorial on creating styles and templates in Word, go to Ch. 3 > Additional Resources > Tutorials: macmillanhighered.com/ launchpad/techcomm11e.

To watch a tutorial on creating styles and templates in Word, go to Ch. 3 > Additional Resources > Tutorials: macmillanhighered.com/ launchpad/techcomm11e.

At this point, your organization is only tentative. When you start to draft, you might find that the pattern you chose isn’t working well or that you need additional information that doesn’t fit into the pattern.

Once you have a tentative plan, write an outline to help you stay on track as you draft. To keep your purpose clearly in mind as you work, you may want to write it at the top of your page before you begin your outline.

SELECTING AN APPLICATION, A DESIGN, AND A DELIVERY METHOD

Once you have a sense of what you want to say, you need to select an application (the type of document), a design, and a delivery method. You have a number of decisions to make:

- Is the application already chosen for me? If you are writing a proposal to submit to the U.S. Department of the Interior, for example, you must follow the department’s specifications for what the proposal is to look like and how it is to be delivered. For most kinds of communication, however, you will likely have to select the appropriate application, such as a set of instructions or a manual. Sometimes, you will deliver an oral presentation or participate in a phone conference or a videoconference.

- What will my readers expect? If your readers expect a written set of instructions, you should present a set of instructions unless some other application, such as a report or a manual, is more appropriate. If they expect to see the instructions presented in a simple black-and-white booklet—and there is no good reason to design something more elaborate than that—your choice is obvious. For instance, instructions for installing and operating a ceiling fan in a house are generally presented in a small, inexpensive booklet with the pages stapled together or on a large, folded sheet of paper. However, for an expensive home-theater system, readers might expect a glossy, full-color manual.

- What delivery method will work best? Related to the question of reader expectations is the question of how you will deliver the document to your readers. For instance, you would likely mail an annual report to your readers and upload it to your company website. You might present industry forecasts on a personal blog or on one sponsored by your employer. You might deliver a user manual for a new type of photo-editing program online rather than in print because the program—and therefore the manual—will change.

It is important to think about these questions during the planning process, because your answers will largely determine the scope, organization, style, and design of the information you will prepare. As early as the planning step, you need to imagine your readers using your information.

During the planning stage, you also must decide when you will need to provide the information and how much you can spend on the project. For instance, for the project on health-promotion programs, your readers might need a report to help them decide what to do before the new fiscal year begins in two months. In addition, your readers might want a progress report submitted halfway through the project. Making a schedule is often a collaborative process: you meet with your main readers, who tell you when they need the information, and you estimate how long the different tasks will take.

You also need to create a budget. In addition to the time you will need to do the project, you need to think about expenses you might incur. For example, you might need to travel to visit companies with different kinds of health-promotion programs. You might need to conduct specialized database searches, create and distribute questionnaires to employees, or conduct interviews at remote locations. Some projects call for usability testing—evaluating the experiences of prospective users as they try out a system or a document. The cost of this testing needs to be included in your budget.