Instructor's Notes

LearningCurve activities on commas are available at the end of the Punctuation section of this handbook.

P1 Commas

Use a comma to set off and separate sentence elements.

P1-

When independent clauses are joined by a coordinating conjunction, a comma is required to tell the reader that another independent clause follows the first one.

![]()

If the independent clauses are brief and unambiguous, a comma is not required, though it is never wrong to include it.

![]()

P1-

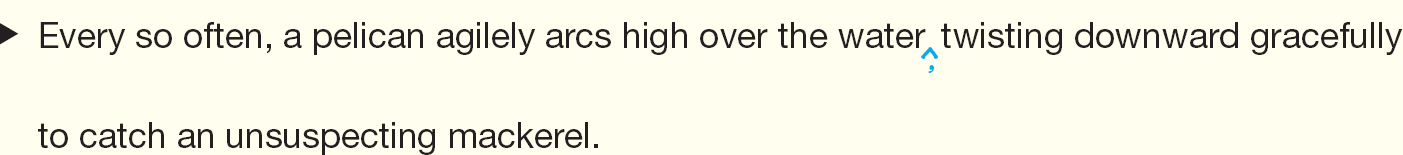

Sentences often begin with words, phrases, or clauses that precede the independent clause and modify an element within it. The comma following each introductory element lets the reader know where the modifying word or phrase ends and the main clause begins.

![]()

![]()

![]()

If an introductory phrase or clause is brief — four words or fewer — the comma may be omitted unless it is needed to prevent misreading.

![]()

P1-

To test whether a word group is nonrestrictive (supplemental, nondefining, and thus nonessential) or restrictive (defining and thus essential), read the sentence with and without the word group. If the sentence is essentially unchanged in meaning without it, the word group is nonrestrictive. Use commas to set it off.

![]()

Conversely, if omitting the word group changes the meaning of the sentence, it is restrictive. In this case, do not use commas.

![]()

Use a comma to set off a nonrestrictive word group at the end of a sentence.

![]()

Use a pair of commas to set off a nonrestrictive word group in the middle of a sentence.

![]()

(See also P2-b.)

P1-

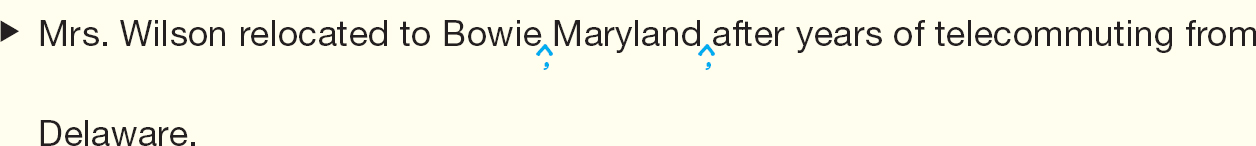

Transitional expressions help the reader follow a writer’s movement from point to point. Parenthetical comments interrupt a sentence with a brief aside. Contrasting expressions are introduced by not, no, or nothing. Absolute phrases modify the whole clause and often include a past or present participle as well as modifiers. By using commas to set off such expressions, you signal that they are additions, supplementing or commenting on the information in the rest of the sentence.

P1-

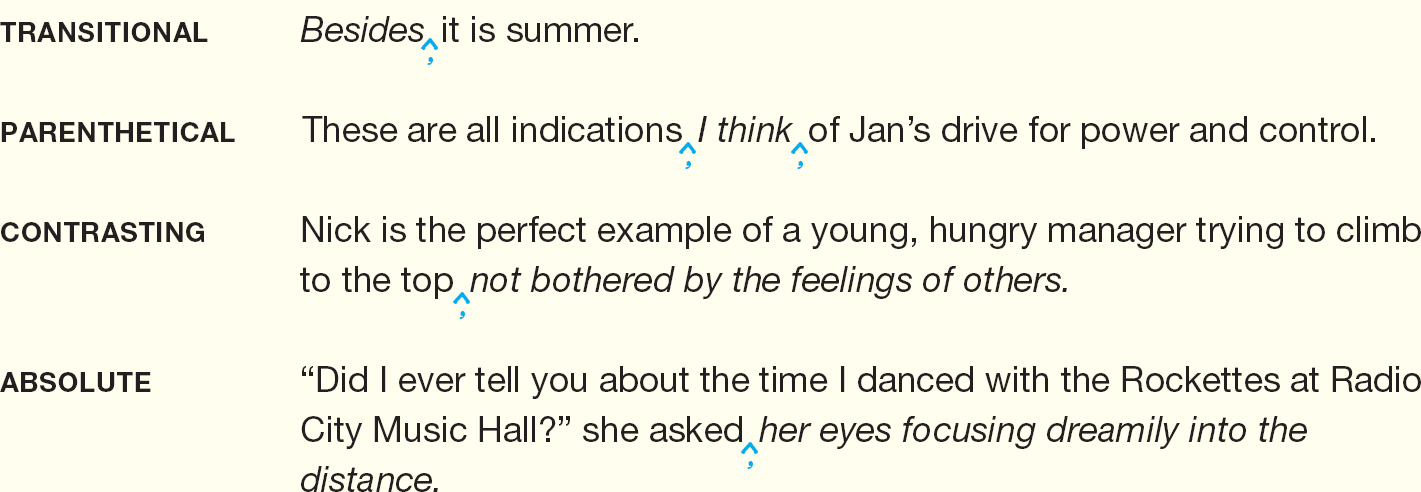

The commas in a series separate the items for the reader.

![]()

Note: Newspapers, magazines, and British publications often omit the comma before the conjunction. In your academic writing, however, include it for clarity.

P1-

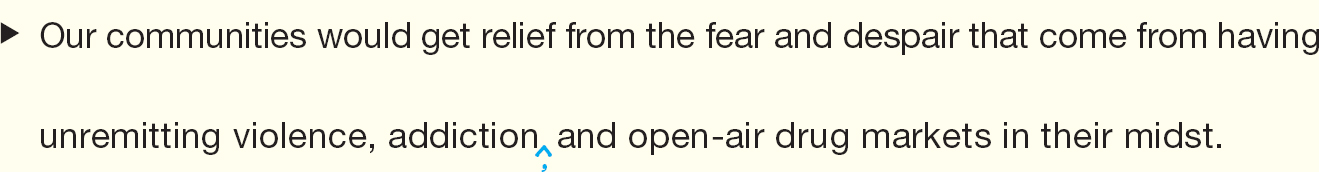

Participial phrases are generally nonrestrictive word groups. When they follow the independent clause in a sentence, they should be set off with commas. See P1-c.

![]()

The comma before the phrase signals the end of the main clause and sets off the important modifying phrase.

Note: If the participial phrase is restrictive, providing essential information, do not use a comma. See P1-c and P2-b.

P1-

The comma, along with the quotation marks, helps the reader determine where the quotation begins and ends. (See also P6.)

P1-

Use commas to set off from the main part of the sentence the name of a person directly addressed by a speaker, words such as yes and no, and mild interjections. Also use a comma to set off questions added to the end of sentences.

P1-

If you can change the order of a series of adjectives or add and between them without changing the meaning, they are coordinate and should be separated with a comma.

![]()

The comma signals that the adjectives are equal, related in the same way to the word modified.

If the adjectives closest to the noun cannot be logically rearranged or linked by and, they are cumulative adjectives and should not be separated by commas.

![]()

P1-

When you include a full date (month, day, and year), use a pair of commas to set off the year.

If you present a date in reverse order (day, month, and year) or if the date is partial, do not add commas.

In large numbers (except four-

![]()

When you write out an address, add commas between the street address, the city, and the state.