Conducting Field Research

In universities, government agencies, and the business world, field research can be as important as library research. In some majors, like education or sociology, as well as in service-

Conduct observational studies.

Observational studies, such as you would conduct when profiling a place (see Chapter 3), are common in college. To conduct an observational study effectively, follow these guidelines:

Planning an Observational Study

To ensure that your observational visits are productive, plan them carefully:

Arrange access if necessary. Visits to a private location (such as a school or business) require special permission, so be sure to arrange your visit in advance. When making your request, state your intentions and goals for your study directly and fully. You may be surprised at how receptive people can be to a college student on assignment. But have a fallback plan in case your request is refused or the business or institution places constraints on you that hamper your research.

Develop a hypothesis. In advance, write down a tentative assumption about what you expect to learn from your study—

your hypothesis. This will guide your observations and notes, and you can adjust your expectations in response to what you observe if necessary. Consider, too, how your presence will affect those whom you are observing, so you can minimize your impact or take the effect of your presence into consideration. Consider how best to conduct the observation. Decide where to place yourself to make your observations most effective. Should you move around to observe from multiple vantage points, or will a single perspective be more productive?

Making Observations

For more about narration, description, and classification, see Chapters 14, 15, and 17.

Strategies for conducting your observation include the following:

Description:Describe in detail the setting and the people you are observing. Note the physical arrangement and functions of the space, and the number, activities, and appearance of the people. Record as many details as possible, draw diagrams or sketches if helpful, and take photographs or videos if allowed (and if those you are observing do not object).

Narration:Narrate the activities going on around you. Try initially to be an innocent observer: Pretend that you have never seen anything like this activity or place before, and explain what you are seeing step by step, even if what you are writing seems obvious. Include interactions among people, and capture snippets of conversations (in quotation marks) if possible.

Analysis and classification: Break the scene down into its component parts, identify common threads, and organize the details into categories.

Take careful notes during your visit if you can do so unobtrusively or immediately afterwards if you can’t. You can use a notebook and pencil, a laptop or tablet, or even a smartphone to record your notes. Choose whatever is least disruptive to those around you. You may need to use abbreviations and symbols to capture your observations on-

Writing Your Observational Study

For more about mapping, clustering, or outlining strategies, see Chapter 11.

Immediately after your visit, fill in any gaps in your notes, and review your notes to look for meaningful patterns. You might find mapping strategies, such as clustering or outlining, useful for discovering patterns in your notes. Take some time to reflect on what you saw. Asking yourself questions like these might help:

How did what I observed fit my own or my readers’ likely preconceptions of the place or activity? Did my observations upset any of my preconceptions? What, if anything, seemed contradictory or out of place?

What interested me most about the activity or place? What are my readers likely to find interesting about it?

What did I learn?

Your purpose in writing about your visit is to share your insights into the meaning and significance of your observations. Assume that your readers have never been to the place, and provide enough detail for it to come alive for them. Decide on the perspective you want to convey, and choose the details necessary to convey your insights.

PRACTICING THE GENRE

Collaborating on an Observational Study

Arrange to meet with a small group (three or four students) for an observational visit somewhere on campus, such as the student center, gym, or cafeteria. Have each group member focus on a specific task, such as recording what people are wearing, doing, or saying, or capturing what the place looks, sounds, and smells like. After twenty to thirty minutes, report to one another on your observations. Discuss any difficulties that arise.

Conduct interviews.

A successful interview involves careful planning before the interview, but it also requires keen listening skills and the ability to ask appropriate follow-

Planning the Interview

Planning an interview involves the following:

Choosing an interview subject. For a profile of an individual, your interview will be with one person; for a profile of an organization, you might interview several people, all with different roles or points of view. Prepare a list of interview candidates, as busy people might turn you down.

Arranging the interview. Give your prospective subject(s) a brief description of your project, and show some sincere enthusiasm for it. Keep in mind that the person you want to interview will be donating valuable time to you, so call ahead to arrange the interview, allow your subject to specify the amount of time she or he can spare, and come prepared.

Preparing for the Interview

In preparation for the interview, consider your objectives:

Do you want details or a general orientation (the “big picture”) from this interview?

Do you want this interview to lead you to interviews with other key people?

Do you want mainly facts or opinions?

Do you need to clarify something you have observed or read? If so, what?

Making an observational visit and doing some background reading beforehand can be helpful. Find out as much as you can about the organization or company (size, location, purpose, etc.), as well as the key people.

Good questions are key to a successful interview. You will likely want to ask a few closed questions (questions that request specific information) and a number of open questions (questions that give the respondent range and flexibility and encourage him or her to share anecdotes, personal revelations, and expressions of attitudes):

| Open Questions | Closed Questions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The best questions encourage the subject to talk freely but stick to the point. You may need to ask a follow-

During the Interview

For an example of a student’s interview notes, see the “Writer at Work” section in Chapter 3.

Another key to good interviewing is flexibility. Ask the questions you have prepared, but also be ready to shift gears to take full advantage of what your subject can offer.

Take notes. Take notes during the interview, even if you are recording your discussion. You might find it useful to divide several pages of a notebook into two columns or to set up a word processing file in two columns. Use the left-

hand column to note details about the scene and your subject or about your impressions overall; in the right- hand column, write several questions and record the answers. Remember that how something is said is as important as what is said. Look for material that will give texture to your writing— gesture, verbal inflection, facial expression, body language, physical appearance (dress, hair) or anything that makes the person an individual. Listen carefully. Avoid interrupting your subject or talking about yourself; rather, listen carefully and guide the discussion by asking follow-

up questions and probing politely for more information. Be considerate. Do not stay longer than the time you were allotted unless your subject agrees to continue the discussion, and show your appreciation for the time you have been given by thanking your subject and offering her or him a copy of your finished project.

Page 620

Following the Interview

After the interview, do the following:

Reflect on the interview. As soon as you finish the interview, find a quiet place to reflect on it and to review and amplify your notes. Asking yourself questions like these might help: What did I learn? What seemed contradictory or surprising about the interview? How did what was said fit my own or my readers’ likely expectations about the person, activity, or place? How can I summarize my impressions?

Also make a list of any questions that arise. You may want to follow up with your subject for more information, but limit yourself to one e-

mail or phone call to avoid becoming a bother.

Thank your subject. Send your interview subject a thank-

you note within twenty- four hours of the interview. Try to reference something specific from the interview, something surprising or thought- provoking. And send your subject a copy of your finished project with a note of appreciation.

PRACTICING THE GENRE

Interviewing a Classmate

Practice interviewing a classmate:

Spend five to ten minutes writing questions and thinking about what you’d like to learn.

Spend ten minutes asking the questions you prepared, but also ask one or more follow-

up questions in response to something your classmate has told you. Following the interview, spend a few minutes thinking about what you learned about your classmate and about conducting an interview. What might you do differently when conducting a formal interview?

Conduct surveys.

Surveys let you gauge the opinions and knowledge of large numbers of people. You might conduct a survey to gauge opinion in a political science course or to assess familiarity with a television show for a media studies course. You might also conduct a survey to assess the seriousness of a problem for a service-

Designing Your Survey

Use the following tips to design an effective survey:

Conduct background research. You may need to conduct background research on your topic. For example, to create a survey on scheduling appointments at the student health center, you may first need to contact the health center to determine its scheduling practices, and you may want to interview health center personnel.

Focus your study. Before starting out, decide what you expect to learn (your hypothesis). Make sure your focus is limited—

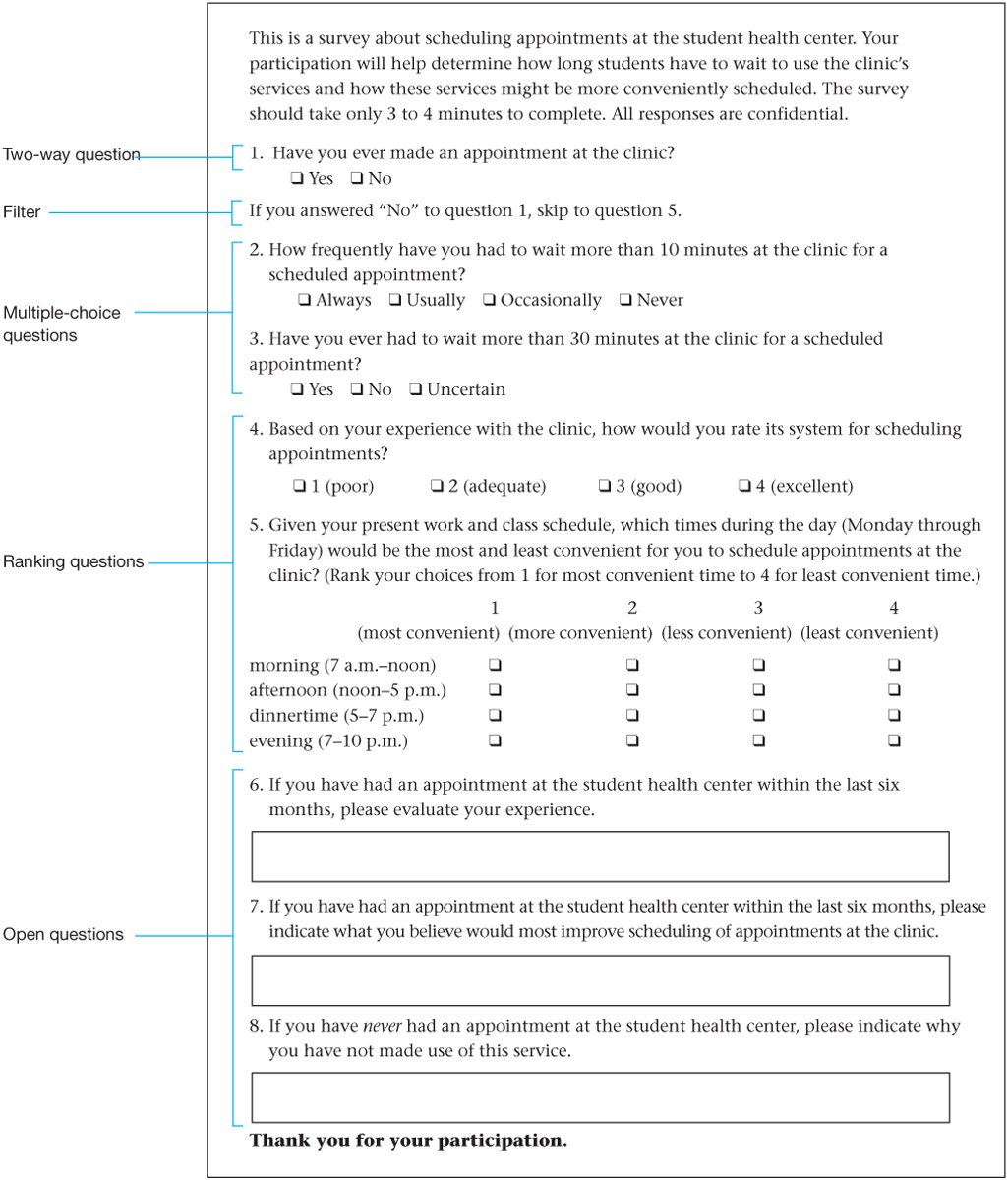

focus on one or two important issues?—so you can craft a brief questionnaire that respondents can complete quickly and easily and so that you can organize and report on your results more easily. Write questions. Plan to use a number of closed questions (questions that request specific information), such as two-

way questions, multiple- and checklist questions (see Figure 21.4). You will also likely want to include a few open questions (questions that give respondents the opportunity to write their answers in their own words). Closed questions are easier to tally, but open questions are likely to provide you with deeper insight and a fuller sense of respondents’ opinions. Whatever questions you develop, be sure that you provide all the answer options your respondents are likely to want, and make sure your questions are clear and unambiguous.choice questions, ranking scale questions,  FIGURE 21.4 Sample Questionnaire: Scheduling at the Student Health Center

FIGURE 21.4 Sample Questionnaire: Scheduling at the Student Health CenterIdentify the population you are trying to reach. Even for an informal study, you should try to get a reasonably representative group. For example, to study satisfaction with appointment scheduling at the student health center, you would need to include a representative sample of all the students at the school—

not only those who have visited the health center. Determine the demographic makeup of your school, and arrange to reach out to a representative sample. Design the questionnaire. Begin your questionnaire with a brief, clear introduction stating the purpose of your survey and explaining how you intend to use the results. Give advice on answering the questions, estimate the amount of time needed to complete the questionnaire, and—

unless you are administering the survey in person— indicate the date by which completed surveys must be returned. Organize your questions by topic, from least to most complicated, or in any order that seems logical, and format your questionnaire so that it is easy to read and complete. Page 622Page 623Test the questionnaire. Ask at least three readers to complete your questionnaire before you distribute it. Time them as they respond, or ask them to keep track of how long they take to complete it. Discuss with them any confusion or problems they experience. Review their responses with them to be certain that each question is eliciting the information you want it to elicit. From what you learn, revise your questions and adjust the format of the questionnaire.

Administering the Survey

The more respondents you have, the better, but constraints of time and expense will almost certainly limit the number. As few as twenty-

You can conduct the survey in person or over the telephone; use an online service such as SurveyMonkey (surveymonkey.com) or Zoomerang (zoomerang.com); e-

Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, face-

Writing the Report

When writing your report, include a summary of the results, as well as an interpretation of what the results mean.

Summarize the results. Once you have the completed questionnaires, tally the results from the closed questions. (If you conducted the survey online, this will have already been done for you.) You can give the results from the closed questions as percentages, either within the text of your report or in one or more tables or graphs. Next, read all respondents’ answers to each open question to determine the variety of responses they gave, and classify the answers. You might classify them as positive, negative, or neutral or try grouping them into more specific categories. Finally, identify quotations that express a range of responses succinctly and engagingly to use in your report.

Interpret the results. Once you have tallied the responses and read answers to open questions, think about what the results mean. Does the information you gathered support your hypothesis? If so, how? If the results do not support your hypothesis, where did you go wrong? Was there a problem with the way you worded your questions or with the sample of the population you contacted? Or was your hypothesis in need of adjustment?

Page 624For more about writing a laboratory report, see Chapter 29.

Write the report. Research reports in the social sciences use a standard format, with headings introducing the following categories of information:

Abstract: A brief summary of the report, usually including one sentence summarizing each section

Introduction: Includes context for the study (other similar studies, if any, and their results), the question or questions the researcher wanted to answer and why this question (or these questions) is important, and the limits of what the researcher expected the survey to reveal

Methods: Includes the questionnaire, identifies the number and type of participants, and describes the methods used for administering the questionnaire and recording data

Results: Includes the data from the survey, with limited commentary or interpretation

Discussion: Includes the researcher’s interpretation of results, an explanation of how the data support the hypothesis (or not), and the conclusions the researcher has drawn from the research