Instructor's Notes

The Instructor's Resource Manual, which includes tips and special challenges for teaching this chapter, is available through the “Resources” panel.

Introduction to Chapter 14

14

Narrating

Narrating is a basic strategy for representing action and events. It can be used to report on events, present information, illustrate abstract ideas, support arguments, explain procedures, and entertain with stories. This chapter begins by describing and illustrating five basic narrating strategies, it includes two types of process narrative—

Narrating Strategies

Strategies such as calendar and clock time, temporal transitions, verb tense, action sequences, and dialogue give narrative its dynamic quality, the sense of events unfolding in time. They also help readers track the order in which the events occurred and understand how they relate to one another.

Use calendar and clock time to create a sequence of events.

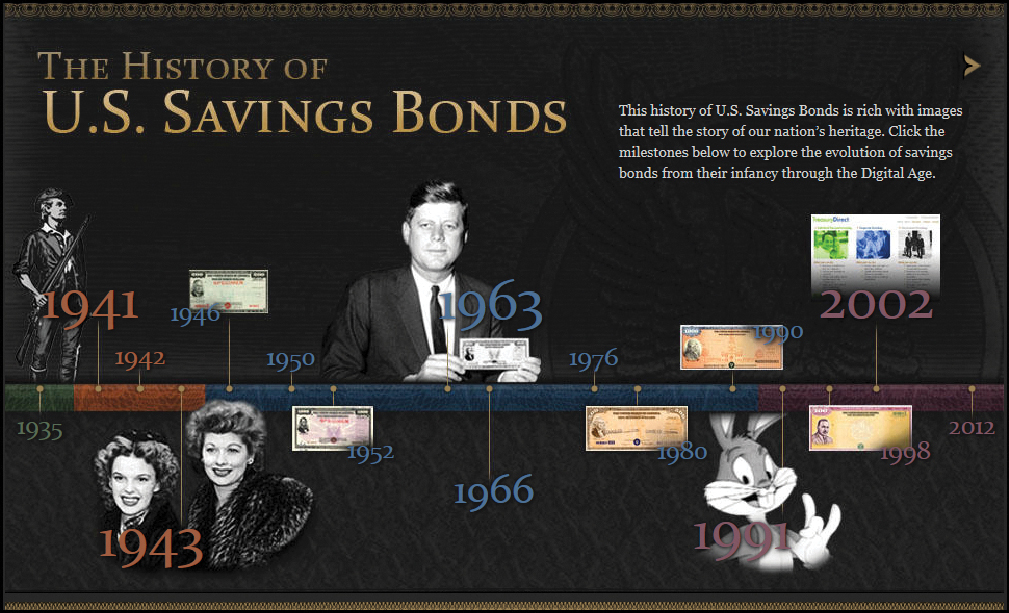

One of the simplest ways of constructing a clear time sequence is to place events on a timeline, with years or precise dates and times clearly marked. Look, for example, at the excerpted portion of a timeline in Figure 14.1, which presents a series of events in the history of U.S. savings bonds. A timeline is not itself a narrative, but it shares with narrative two basic elements:

Events are presented in chronological order.

Each event is “time-

stamped,” so that readers can clearly understand when events occurred in relation to one another.

Look now at a brief but fully developed narrative reconstructing the discovery of the bacterial cause of stomach ulcers. This narrative was written by Martin J. Blaser for Scientific American, a journal read primarily by nonspecialists interested in science. As you read, notice the same narrating strategies you saw in the timeline in Figure 14.1: sequencing events in chronological order and specifying when each event occurred:

Blaser cites specific years, months, days, and a holiday to convey the passage of time and indicate when each event occurred.

In 1979 J. Robin Warren, a pathologist at the Royal Perth Hospital in Australia, made a puzzling observation. As he examined tissue specimens from patients who had undergone stomach biopsies, he noticed that several samples had large numbers of curved and spiral-

Warren, aided by an enthusiastic young trainee named Barry J. Marshall, also had difficulty growing the unknown bacteria in culture. He began his efforts in 1981. By April 1982 the two men had attempted to culture samples from 30-

—MARTIN J. BLASER, “The Bacteria behind Ulcers”

In addition to calendar time (years, months, days), writers sometimes also refer to clock time (hours, minutes, seconds). Here is a brief narrative from an essay profiling the emergency room at Bellevue Hospital in New York City:

The references to clock time establish the sequence and contribute to dramatic intensity

9:05 p.m. An ambulance backs into the receiving bay, its red and yellow lights flashing in and out of the lobby. A split second later, the glass doors burst open as a nurse and an attendant roll a mobile stretcher into the lobby. When the nurse screams, “Emergency!” the lobby explodes with activity as the way is cleared to the trauma room. Doctors appear from nowhere and transfer the bloodied body of a black man to the treatment table. Within seconds his clothes are stripped away.

—GEORGE SIMPSON, “The War Room at Bellevue”

EXERCISE 14.1

Skim Gabriel Thompson’s “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields” in Chapter 3, and underline the references to calendar and clock time. How do you think these time markers function in the narrative? What do they tell you about the impression Thompson wants to create about that period of his life?

Use temporal transitions to establish an action sequence.

For a more extensive list of transitions showing temporal relationships, see Chapter 13.

Whereas writers tend to use calendar and clock time sparingly, they regularly use temporal transitions such as when, at that moment, before, and while to establish a clear sequence of actions in narrating onetime or recurring events.

Onetime Events To see how temporal transitions work, let us look at the concluding paragraphs of a remembered-

Baker uses temporal transitions to show what he and Smith were doing after the flight test.

Back at the flight line, when I’d cut the ignition, he climbed out and tramped back toward the ready room while I waited to sign the plane in. When I got there he was standing at a distance talking to my regular instructor. His talk was being illustrated with hand movements, as pilots’ conversations always were, hands executing little loops and rolls in the air. After he did the falling-

“Smith just said you gave him the best check flight he’s ever had in his life,” he said. “What the hell did you do to him up there?”

“I guess I just suddenly learned to fly,” I said.

—RUSSELL BAKER, “Smooth and Easy”

Look closely at the two transitions in the first sentence. The word when presents actions in chronological order (first Baker stopped the plane, and then Smith got out). While performs a different function, showing that the next two actions occurred at the same time (Baker waited to sign in as the check pilot returned to the ready room). There is nothing complicated or unusual about this set of actions, but it would be hard to represent them in writing without temporal transitions.

Recurring Events Temporal transitions also enable writers to narrate recurring events. In the following narrative by Monica Sone about her daily life in an internment camp for Japanese Americans during World War II, we can see how transitions (highlighted) help the writer represent actions she routinely performed:

With the time marker first, Sone starts describing her typical work routine. In the third sentence, she tells of her surreptitious actions in the first few months and every morning.

First I typed on pink, green, blue and white work sheets the hours put in by the 10,000 evacuees, then sorted and alphabetized these sheets, and stacked them away in shoe boxes. My job was excruciatingly dull, but under no circumstances did I want to leave it. The Administration Building was the only place which had modern plumbing and running hot and cold water; in the first few months and every morning, after I had typed for a decent hour, I slipped into the rest room and took a complete sponge bath with scalding hot water. During the remainder of the day, I slipped back into the rest room at inconspicuous intervals, took off my head scarf and wrestled with my scorched hair. I stood upside down over the basin of hot water, soaking my hair, combing, stretching and pulling at it.

—MONICA SONE, “Camp Harmony”

EXERCISE 14.2

Turn to Anastasia Toufexis’s “Love: The Right Chemistry” in Chapter 4. Read paragraph 3, underlining the temporal transitions Toufexis uses to present the sequence of evolutionary changes that may have contributed to the development of romantic love. How important are these transitions in helping you follow her narrative?

Use verb tense to place actions in time.

In addition to time markers like calendar time and temporal transitions, writers use verb tense to represent action in writing and to help readers understand when each action occurred in relation to other actions.

Onetime Events Writers typically use the past tense to represent onetime events that began and ended in the past. Here is a brief passage from a remembered-

Wu uses the simple past tense to indicate that actions occurred in a linear sequence.

Once, when I was 5 or 6, I interrupted my mother during a dinner with her friends and told her that I disliked the meal. My mother’s eyes transformed from serene pools of blackness into stormy balls of fire. “Quiet!” she hissed, “do you not know that silent waters run deep?”

—AMY WU, “A Different Kind of Mother”

In the next example, by Chang-

Lee uses both the simple past (amassed, needed, moved) and past perfect (had hoped) tenses.

When Uncle Chul amassed the war chest he needed to open the wholesale business he had hoped for, he moved away from New York.

—CHANG-RAE LEE, “Uncle Chul Gets Rich”

You do not have to know that amassed is simple past tense and had hoped is past perfect tense to know that the uncle’s hopes came before the money was amassed. In fact, most readers of English can understand complicated combinations of tenses without knowing their names.

Let us look at another verb tense combination used frequently in narrative: the simple past and the past progressive:

Malcolm X uses the simple past (overheard, was) and past progressive (was leaving, was appearing) tenses.

When Dinah Washington was leaving with some friends, I overheard someone say she was on her way to the Savoy Ballroom where Lionel Hampton was appearing that night—

—MALCOLM X, The Autobiography of Malcolm X

This combination of tenses plus the temporal transition when shows that the two actions occurred at the same time in the past. The first action (“Dinah Washington was leaving”) continued during the period that the second action (“I overheard”) occurred.

Occasionally, writers use the present instead of the past tense to narrate onetime events. Process narratives and profiles typically use the present tense to give the story a sense of “you are there” immediacy:

Edge uses present-

Slowly, the dank barroom fills with grease-

I’m not leaving until I eat this thing, I tell myself.

—JOHN T. EDGE, “I’m Not Leaving Until I Eat This Thing”

Recurring Events Verb tense, usually combined with temporal transitions, can also help writers narrate events that occurred routinely:

Morris uses the helping verb would along with temporal transitions to show recurring actions.

Many times, walking home from work, I would see some unknowing soul venture across that intersection against the light and then freeze in horror when he saw the cars ripping out of the tunnel toward him. . . .

—WILLIE MORRIS, North toward Home

Notice also that Morris shifts to the simple past tense when he moves from recurring actions to an action that occurred only once. He signals this shift with the temporal transition on one occasion.

EXERCISE 14.3

Turn to Jean Brandt’s essay, “Calling Home,” in Chapter 2. Read paragraph 3 and underline the verbs, beginning with got, took, knew, and didn’t want in the first sentence. Brandt uses verb tense to reconstruct her actions and reflect on their effectiveness. Notice also how verb tense helps you follow the sequence of actions Brandt took.

Use action sequences for vivid narration.

The narrating strategy we call action sequences uses active verbs and modifying phrases and clauses to present action vividly. Action sequences are especially suited to representing intense, fast-

Though Plimpton uses active verbs, he describes most of the action through modifying phrases and clauses.

Since in the two preceding plays the concentration of the play had been elsewhere, I had felt alone with the flanker. Now, the whole heave of the play was toward me, flooding the zone not only with confused motion but noise—

—GEORGE PLIMPTON,Paper Lion

By piling up action sequences, Plimpton reconstructs for readers the texture and excitement of his experience on the football field. He uses the two most common kinds of modifiers that writers employ to present action sequences:

Participial phrases: tearing by me, stopping suddenly, moving past me at high speed

Absolute phrases: his cleats thumping in the grass, his legs pinwheeling, the row of cleats flicking up a faint wake of dust behind

Combined with vivid sensory description (the creak of football gear, the strained grunts of effort, the faint ah-

EXERCISE 14.4

Turn to paragraph 2 of Amanda Coyne’s profile essay “The Long Good-Bye: Mother’s Day in Federal Prison” in Chapter 3. Underline any action sequences you find in this brief paragraph. Then reflect on how they help the reader envision the scene in the prison’s visiting room.

EXERCISE 14.5

Record several brief—

If you cannot record a televised game, narrate a live-

Use dialogue to dramatize events.

Dialogue is most often used in narratives that dramatize events. It reconstructs choice bits of conversation, rather than trying to present an accurate and complete record. In addition to showing people interacting, dialogue can give readers insight into character and relationships. Dialogue may be quoted to make it resemble the give-

The following example from Gary Soto’s Living up the Street shows how a narrative can combine quoted and summarized dialogue. In this passage, Soto recalls his first experience as a migrant worker in California’s San Joaquin Valley:

Soto uses signal phrases with the first two quotations but not with the third, where it is clear who is speaking.

“Are you tired?” she asked.

“No, but I got a sliver from the frame,” I told her. I showed her the web of skin between my thumb and index finger. She wrinkled her forehead but said it was nothing.

“How many trays did you do?”

The fourth quotation, “thirty-

I looked straight ahead, not answering at first. I recounted in my mind the whole morning of bend, cut, pour again and again, before answering a feeble “thirty-

—GARY SOTO, “One Last Time”

For more on deciding when to quote, see Chapter 2 and Chapter 23.

Quoted dialogue is easy to recognize, of course, because of the quotation marks. Summarized dialogue can be harder to identify. In this case, however, Soto embeds signal phrases (she told me and she then talked) in his narrative. Summarizing leaves out information the writer decides readers do not need. In this passage about a remembered event, Soto has chosen to focus on his own feelings and thoughts rather than his mother’s.

EXERCISE 14.6

Read the essay “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields” in Chapter 3, and consider Gabriel Thompson’s use of both direct quotation and summaries for reporting speech. When does Thompson choose to quote directly, and why might he have made this decision?

EXERCISE 14.7

If you wrote a remembered-