Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,”" selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel."

Gabriel Thompson A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields

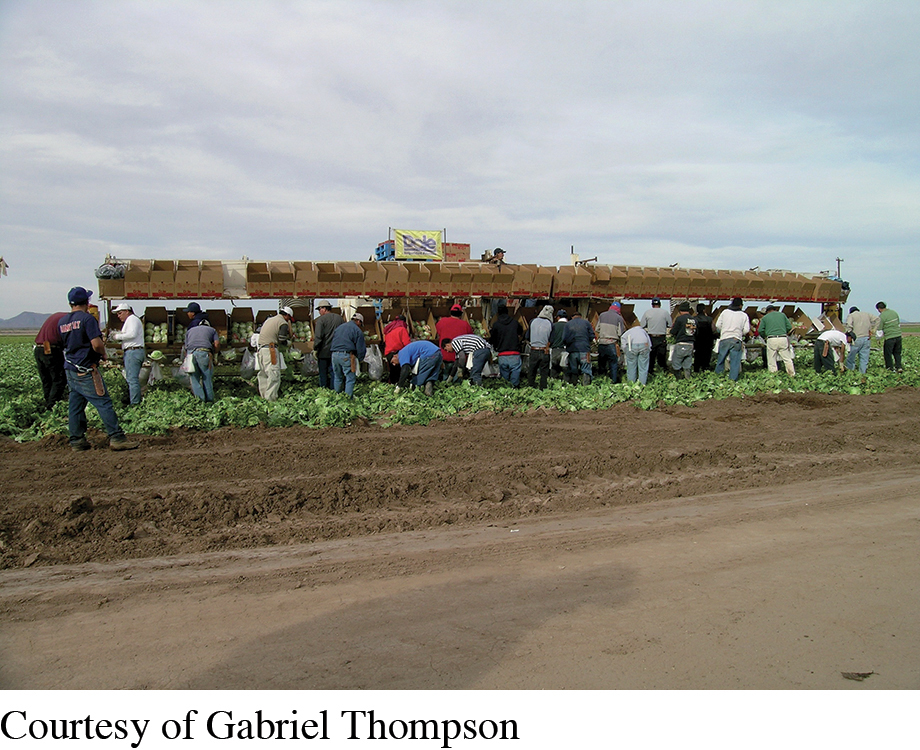

GABRIEL THOMPSON has worked as a community organizer and written extensively about the lives of undocumented immigrants in the United States. His books include There’s No José Here: Following the Hidden Lives of Mexican Immigrants (2006), Calling All Radicals: How Grassroots Organizers Can Help Save Our Democracy (2007), and Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won’t Do (2010), from which the following selection is taken. The photograph showing lettuce cutters at work is from Thompson’s blog, Working in the Shadows.

“A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields” falls into the category of immersion journalism, a cultural ethnography that uses undercover participant observation over an extended period of time to get an insider’s view of a particular community.

As you read, consider the ethical implications of this kind of profile:

What does Thompson’s outsider status enable him to understand—

or prevent him from understanding— about the community? How does Thompson avoid—

or fail to avoid— stereotyping or exploiting the group being profiled? Toward the end, Thompson tells us that one of the workers “guesses” that he “joined the crew . . . to write about it” (par. 17). Not all participant-

observers go undercover; why do you think Thompson chose to do so? What concerns would you have if you were the writer or if you were a member of the group being profiled?

1

I wake up staring into the bluest blue I’ve ever seen. I must have fallen into a deep sleep because I need several seconds to realize that I’m looking at the Arizona sky, that the pillow beneath my head is a large clump of dirt, and that a near-

2

I stand up gingerly. It’s only my third day in the fields, but already my 30-

3

“Manuel! Gabriel! Let’s go! ¡Vámonos!” yells Pedro, our foreman. Our short break is over. Two dozen crew members standing near the lettuce machine are already putting on gloves and sharpening knives. Manuel and I hustle toward the machine, grab our own knives from a box of chlorinated water, and set up in neighboring rows, just as the machine starts moving slowly down another endless field.

4

Since the early 1980s, Yuma, Ariz., has been the “winter lettuce capital” of America. Each winter, when the weather turns cold in Salinas, California—

5

America’s lettuce industry actually needs people like me. Before applying for fieldwork at the local Dole headquarters, I came across several articles describing the causes of a farmworker shortage. The stories cited an aging workforce, immigration crackdowns, and long delays at the border that discourage workers with green cards who would otherwise commute to the fields from their Mexican homes.1 Wages have been rising somewhat in response to the demand for laborers (one prominent member of the local growers association tells me average pay is now between $10 and $12 an hour), but it’s widely assumed that most U.S. citizens wouldn’t do the work at any price. Arizona’s own Senator John McCain created a stir in 2006 when he issued a challenge to a group of union members in Washington, D.C. “I’ll offer anybody here $50 an hour if you’ll go pick lettuce in Yuma this season, and pick for the whole season,” he said. Amid jeers, he didn’t back down, telling the audience, “You can’t do it, my friends.”

6

On my first day I discover that even putting on a lettuce cutter’s uniform is challenging (no fieldworkers, I learn, “pick” lettuce). First, I’m handed a pair of black galoshes to go over my shoes. Next comes the gancho, an S-

7

The crew is already working in the field when Pedro walks me out to them and introduces me to Manuel. Manuel is holding an 18-

Pedro offers me a suggestion. “Act like the lettuce is a bomb. . . .

8

I bend over, noticing that most of the crew has turned to watch. I take my knife and make a tentative sawing motion where I assume the trunk to be, though I’m really just guessing. Grabbing the head with my left hand, I straighten up, doing my best to imitate Manuel. Only my lettuce head doesn’t move; it’s still securely connected to the soil. Pedro steps in. “When you make the first cut, it is like you are stabbing the lettuce.” He makes a quick jabbing action. “You want to aim for the center of the lettuce, where the trunk is,” he says.

9

Ten minutes later, after a couple of other discouraging moments, I’ve cut maybe 20 heads of lettuce and am already feeling pretty accomplished. I’m not perfect: If I don’t stoop far enough, my stab—

10

Pedro offers me a suggestion. “Act like the lettuce is a bomb,” he says. “Imagine you’ve only got five seconds to get rid of it.”

11

Surprisingly, that thought seems to work, and I’m able to greatly increase my speed. For a minute or two I feel euphoric. “Look at me!” I want to shout at Pedro; I’m in the zone. But the woman who is packing the lettuce into boxes soon swivels around to face me. “Look, this lettuce is no good.” She’s right: I’ve cut the trunk too high, breaking off dozens of good leaves, which will quickly turn brown because they’re attached to nothing. With her left hand she holds the bag up, and with her right she smashes it violently, making a loud pop. She turns the bag over and the massacred lettuce falls to the ground. She does the same for the three other bags I’ve placed on the extension. “It’s okay,” Manuel tells me. “You shouldn’t try to go too fast when you’re beginning.” Pedro seconds him. “That’s right. Make sure the cuts are precise and that you don’t rush.”

12

So I am to be very careful and precise, while also treating the lettuce like a bomb that must be tossed aside after five seconds.

13

That first week on the job was one thing. By midway into week two, it isn’t clear to me what more I can do to keep up with the rest of the crew. I know the techniques by this time and am moving as fast as my body will permit. Yet I need to somehow double my current output to hold my own. I’m able to cut only one row at a time while Manuel is cutting two. Our fastest cutter, Julio, meanwhile can handle three. But how someone could cut two rows for an hour—

14

That feeling aside, what strikes me about our 31-

15

Two months in, I make the mistake of calling in sick one Thursday. The day before, I put my left hand too low on a head of lettuce. When I punched my blade through the stem, the knife struck my middle finger. Thanks to the gloves, my skin wasn’t even broken, but the finger instantly turned purple. I took two painkillers to get through the afternoon, but when I wake the next morning it is still throbbing. With one call to an answering machine that morning, and another the next day, I create my own four-

16

The surprise is that when I return on Monday, feeling recuperated, I wind up having the hardest day of my brief career in lettuce. Within hours, my hands feel weaker than ever. By quitting time—

17

An older co-

18

Mateo is an unusual case. There aren’t many other farmworkers who are still in the fields when they reach their 50s. It’s simply not possible to do this work for decades and not suffer a permanently hunched back, or crooked fingers, or hands so swollen that they look as if someone has attached a valve to a finger and pumped vigorously. The punishing nature of the work helps explain why farmworkers don’t live very long; the National Migrant Resources Program puts their life expectancy at 49 years.

19

“Are you cutting two rows yet?” Mateo asks me. “Yes, more or less,” I say. “I thought I’d be better by now.” Mateo shakes his head. “It takes a long time to learn how to really cut lettuce. It’s not something that you learn after only one season. Three, maybe four seasons—

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Switching perspectives.

Thompson temporarily joined a community of lettuce cutters to get an insider’s perspective on their work. Think about your own experience as a member of a group that was visited and observed, even for a short period of time. Perhaps an administrator visited one of your classes or a potential coach or recruit observed your team. Consider what it was like being studied by a stranger. Your instructor may ask you to post your thoughts about the experience on a discussion board or to discuss them with other students in class. Use these questions to get started:

As an insider, how did you and the other group members feel about being the subject of someone else’s gaze?

What were you told about why your group was being visited and what assumptions or concerns did you have about the visitor? Were you concerned about the visitor’s motives—

for example, wondering if the person was really there to evaluate the group or its members? Suppose Thompson wanted to write a piece of immersion journalism about a community (such as a religious group, sports team, fraternity, or sorority) of which you are a member. What elements of Thompson’s profile, if any, would cause you to trust or distrust his reporting? What ethical challenges might immersion journalists like Thompson face by going undercover?

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

SPECIFIC INFORMATION ABOUT THE SUBJECT: USING QUOTATION, PARAPHRASE, AND SUMMARY

Profile writers—

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a few paragraphs analyzing Thompson’s decisions about how to present information from different sources in “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields”:

Skim the essay to find at least one example of a quotation and one paraphrase or summary of information gleaned from an interview or from background research.

Why do you think Thompson chooses to quote certain things and paraphrase or summarize other things? What could be a good rule of thumb for you to apply when deciding whether to quote, paraphrase, or summarize? (Note that when writing for an academic audience, in a paper for a class or in a scholarly publication, all source material—

whether it is quoted, paraphrased, or summarized— should be cited.)

To learn more about quotation, paraphrase, and summary, see Chapter 23, “Using Sources to Support Your Ideas.”

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: NARRATING AN EXTENDED PERIOD

Some profile writers do field research, observing and interviewing over an extended period of time. As an immersive journalist, Thompson spent more than two months as a member of one crew. To give readers a sense of the chronology of events, he uses time cues (such as calendar and clock time, transitions like next, and prepositional phrases such as on my first day). These cues are especially useful because Thompson’s narrative does not always follow a straightforward chronology. He also describes the process of cutting lettuce in detail. (For more about time markers, see “Assess the basic features” earlier in this chapter and Chapter 14, “Narrating Strategies”; for more about process narration, see Chapter 14, “Narrating a Process.”)

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing Thompson’s use of time cues and process narration in “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields”:

Skim the profile, highlighting the time cues. Why do you imagine Thompson decided not to follow a linear chronology? How well does he use time cues to keep readers from becoming confused?

Why do you think Thompson devotes so much space (pars. 6–12) to narrating the process of cutting lettuce? What does this detailed narrative offer to readers?

THE WRITER’S ROLE: GOING UNDERCOVER

Like Coyne, Thompson acts as a participant-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing Thompson’s use of the participant-

Skim the text, noting at least one place where Thompson

reminds readers of his status as an outsider (for example, when he refers to a coworker as a “near-

stranger” [par. 1]); tells readers about something he thinks will be unfamiliar to them (for example, when he explains that people do not “‘pick’ lettuce” [par. 6]);

calls attention to his own incompetence or failings (for example, when he describes his first attempt to cut lettuce [par. 8]).

Why do you think Thompson tells us about his errors and reminds us that he is an outsider? What effect are these moves likely to have on his audience?

How do the writers whose profiles appear in this chapter use their outsider status to connect with readers?

A PERSPECTIVE ON THE SUBJECT: PROFILING A CONTROVERSIAL ISSUE

Two other profiles in this chapter also touch on a controversial subject about which people have strong opinions. Cable addresses the commercialization of death, and Coyne, the unfairness of the legal system. Although profiles do not usually make an explicit argument the way essays arguing a position do, they convey the writer’s perspective on the issue and try to influence readers’ thinking about it.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a few paragraphs analyzing Thompson’s perspective in “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields”:

Skim the profile looking for a passage or two where you get a clear understanding of the issue and what Thompson thinks about it.

Consider also what you learn about the issue and Thompson’s perspective on it from the title of the profile, “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields,” and the title of the book from which it is excerpted, Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won’t Do.

If Thompson were to make an explicit argument supporting his view of this issue, how do you think his argument would likely differ from this profile? How effectively does Thompson use the genre of the investigative profile to achieve his purpose? How well suited do you think the profile genre is for arguing a position on a controversial issue, as well as informing readers about it?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Immersing yourself.

Thompson’s experience suggests two possible avenues for research: You could embed yourself in a group, participating alongside group members, and then write about that experience. For example, you might join a club on campus or try an unusual sport. Alternatively, you could observe life in an unfamiliar group, watching how a meeting or event unfolds, interviewing members to learn about their practices, and conducting additional research to learn about the group.