Maya Gomez Report: Possible Solutions to the Kidney Shortage

If your instructor has asked you to compose a report, turn to the Guide to Writing for help choosing a topic, finding sources, synthesizing information from those sources, and composing a report. Use the Starting Points chart to locate the sections you need.

FOR THIS REPORT—

As you read,

consider why Gomez begins her report with an anecdote about the Herrick brothers.

notice that Gomez includes two graphs and headings. What do you think they contribute to the report?

answer the questions in the margins. Your instructor may ask you to post to a class blog or discussion board or bring your responses to class.

![]() Basic Features

Basic Features

An Informative Explanation

A Clear, Logical Organization

Smooth Integration of Sources

Appropriate Explanatory Strategies

How does knowing this history help readers understand the topic?

1

The “first successful kidney transplant” took place in 1954 when Ronald Herrick donated one of his kidneys to his identical twin Richard, who was dying of kidney disease (“Milestones”). Richard and Ronald’s successful tandem surgery was an historic event ushering in the era of kidney transplantation. Today, kidney transplantation has become routine. Because of improvements in blood and tissue typing, together with the development of powerful immunosuppressant drugs, it is no longer necessary for an identical twin or even a relative to make the donation. As long as the donor and recipient are compatible, kidneys can be transplanted from strangers as well as relatives, from living as well as deceased donors.

Why do you think Gomez explains what Figure 1 shows?

2

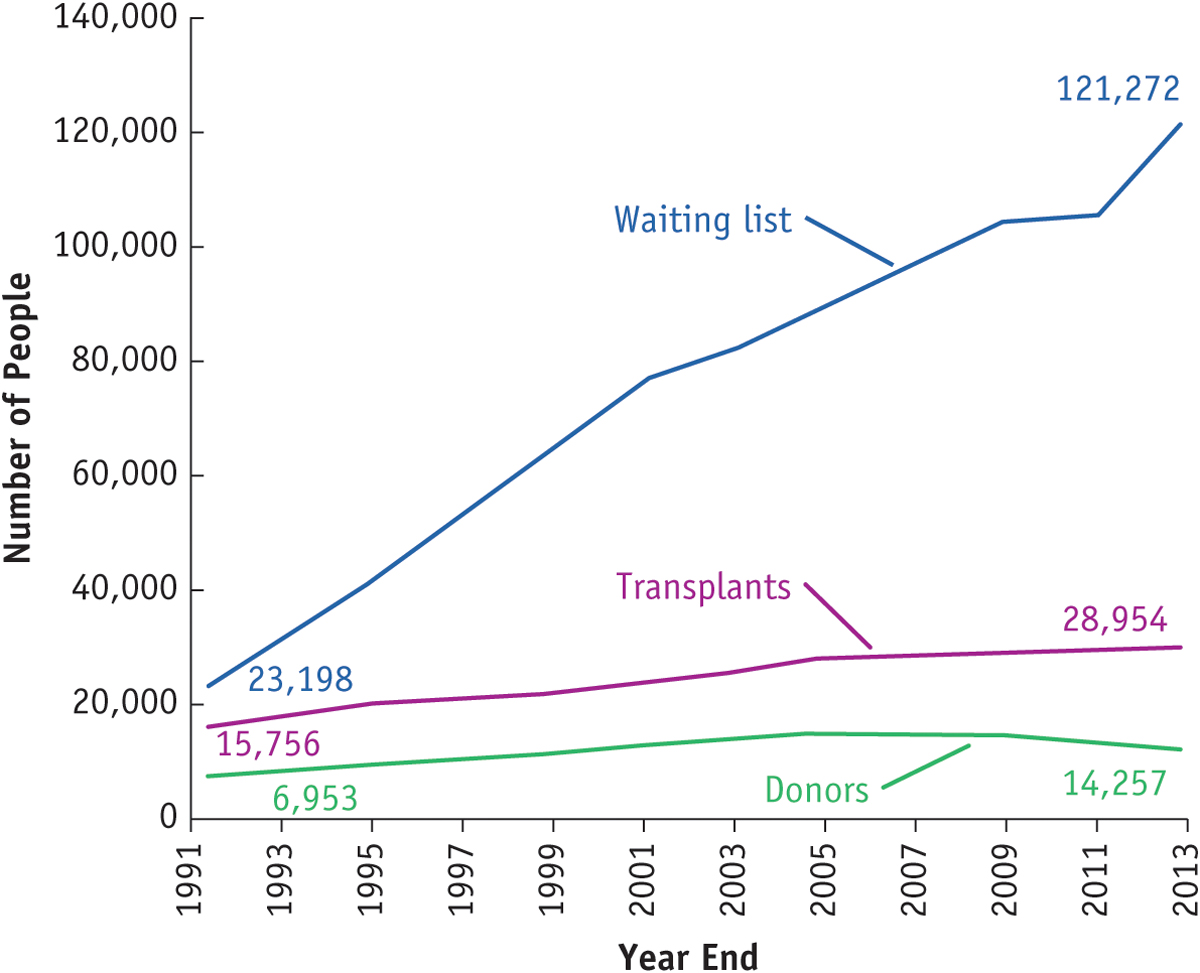

Nevertheless, the shortage of kidneys has gotten worse, not better . According to the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), more than 120,000 people with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) are on the U.S. transplant waiting list, with “nearly 3,000 new patients” joining the list every month and an estimated 12 patients dying every day waiting for a kidney (“Organ Donation”). As fig. 1 below shows, the number of people with kidney disease has risen dramatically during recent decades.

How useful is this forecast?

3

Even though the number of donated kidneys has doubled, the gap between the number of people on the waiting list and the number of transplantations performed has widened because of the scarcity of available kidneys. Clearly, the number of donated kidneys falls far short of the number needed. This report will survey an array of ideas that have been proposed to encourage people to donate their kidneys, including changing to an opt-

How do the transitions help readers?

Change from Opt-

4

There has been some discussion about changing from an opt-

How clear are these causal explanations?

5

Those who oppose changing to an opt-

Facilitate Paired Kidney Exchanges

How effective are this subheading and topic sentence?

6

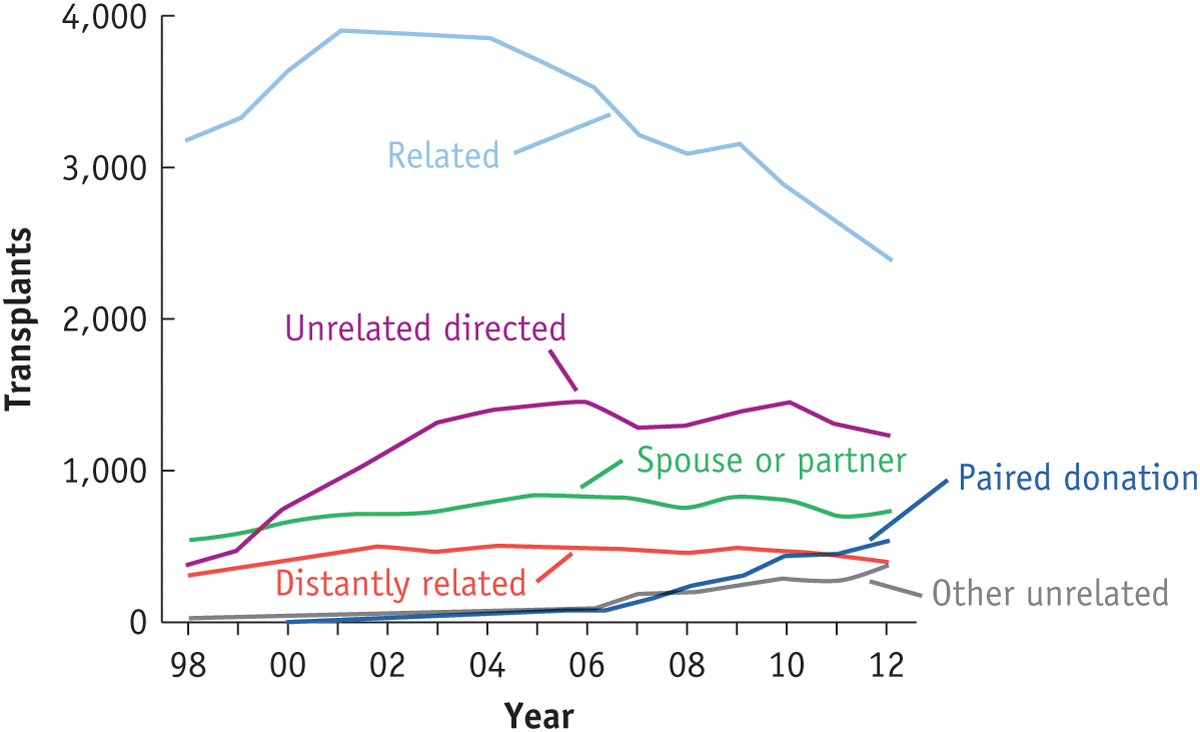

Unlike the question of whether to change to an opt-

How clear are these definitions?

7

The key passage of NOTA prohibiting compensation states that “it shall be unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation” (sec. 301a). “Valuable consideration” is a term used in law to refer to in-

8

Advances in computer matching have also made possible long chains of paired kidney exchanges. Unfortunately, however, the total number of living donor transplants, including those from paired kidney exchanges, is relatively low and has been declining in recent years. Research suggests that the decline may be due largely to the financial crisis of 2007 that led to housing foreclosures and high unemployment, making the financial disincentives to donating an even greater hardship for many people (Rodriguez et al.).

Remove Disincentives

9

Most stakeholders agree that it’s a good idea to remove at least some of the disincentives to donation, such as travel expenses to the transplant center. The National Kidney Foundation, one of the most conservative advocacy groups, had been adamantly opposed to financial compensation of any kind since 2002 (“Financial”). But in 2009, when the waiting list reached 100,000, the NKF announced that it planned to work with Congress to craft legislation that will address all the barriers to donation (“Organ Shortage”). The NKF’s “End the Wait!” campaign supports reimbursing living donors “for all expenses involved in the donation, including lost wages” and also subsidizing donors’ “state-

10

According to Transplant Living, a service of the nonprofit organization UNOS, a number of states have already passed legislation to reduce the burden on living donors (“Financing”). Congress has also passed two laws: the “Organ Donor Leave Act” (1999), which gives federal employees who donate kidneys paid leave, and the “Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act” (2004), which reimburses travel and living expenses for low-

Offer Incentives

11

The idea that money should be offered, not just to counter the financial costs associated with donating, but also as an incentive to encourage donors, is the most controversial of all the proposals that have been considered. In 2014, the thirtieth anniversary of NOTA, debate heated up on financial incentives. A radical proposal, aptly titled “Cash for Kidneys,” was published in The Wall Street Journal by two respected economists, Julio Elías and Nobel Laureate Gary Becker, who argue that the only way to “close the gap between the demand and supply of kidneys” is to pay people for their kidneys.

12

For the NKF and other opponents of financial compensation, the Becker and Elías proposal to pay for kidneys recalls the 1983 proposal by Dr. Barry Jacobs to buy kidneys from healthy poor people in Third World countries and sell them to Americans (Sullivan). It was Jacobs’ plan that led to NOTA’s strict prohibition against compensation in the first place. And, as we have seen, although Congress has been willing to modify NOTA to permit paired kidney exchanges and reimburse some donor expenses, it has staunchly resisted any substantial change to the valuable consideration clause.

13

The main arguments against financial compensation — the immorality of treating body parts as commodities and using poor people’s kidneys as spare parts for the rich — have not changed since NOTA was passed (Gomez). What has changed in the last thirty years, however, is that the kidney shortage has grown to crisis proportions and that desperate people have found ways around the law by means of transplant tourism and the illegal organ trade. But as Sally Satel, herself a kidney transplant recipient, acknowledges in “The Case for Compensating Kidney Donors”: “It is easy to condemn the black market and the patients who patronize it. But you can’t fault people for trying to save their own lives” (par. 9).

Note the sources’ dates, publication venues, and authors. How appropriate do the sources appear to be? Does the selection seem fair and balanced?

Works Cited

Becker, Gary S., and Julio J. Elías. “Cash for Kidneys: The Case for a Market in Organs.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones, 18 Jan. 2014, 4:58 p.m., www.wsj.com/

“Financial Incentives for Organ Donation.” National Kidney Foundation, 1 Feb. 2003, www.kidney.org/

“Financing Living Donation.” Transplant Living, United Network for Organ Sharing, www.transplantliving.org/

Gomez, Maya. “Satel vs. the National Kidney Foundation: Should Kidney Donors Be Compensated?” Paper, Huntly College, Writing 1101, 2015.

McIntosh, James. “Organ Donation: Is an Opt-

“Milestones in Organ Transplantation.” National Kidney Foundation, www.kidney.org/

“Organ Donation and Transplantation Statistics.” National Kidney Foundation, 8 Sept. 2014, www.kidney.org/

“Organ Shortage Needs Multi-

Rodriguez, James R., et al. “The Decline in Living Kidney Donation in the United States: Random Variation or Cause for Concern?” Transplantation, vol. 96, no. 9, 2013, doi:10.1053/

Satel, Sally. “The Case for Compensating Kidney Donors.” Pacific Standard, Miller-

Sullivan, Walter. “Buying of Kidneys of Poor Attacked.” The New York Times, 24 Sept. 1983, www.nytimes.com/

United States, Congress, House. Charlie W. Norwood Living Donation Act. Government Printing Office, 7 Dec. 2007. 110th Congress, House Report 710.

---, ---, ---. National Organ Transplant Act, Government Publishing Office, 19 Oct. 1984. 98th Congress, House Report 98-

---, Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. “Selected Statutory and Regulatory History of Organ Transplantation.” Organdonor.gov: Donate the Gift of Life, www.organdonor.gov/