Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,” selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel.

Naomi Rose Captivity Kills Orcas

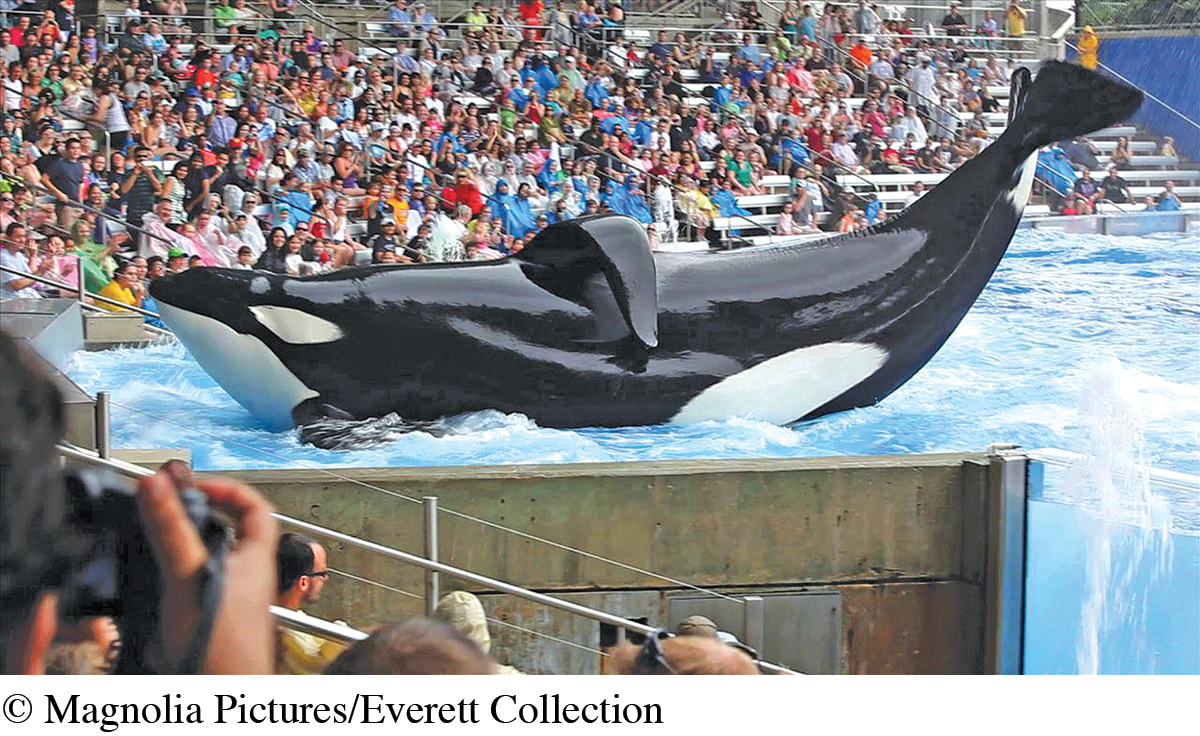

NAOMI ROSE is a scientist specializing in marine mammals at the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington, D.C. Author of numerous articles and book chapters for scientists and the general public, Rose regularly presents university lectures, serves on task forces, and testifies before Congress. She has also worked with the Merlin Entertainments Group to build sanctuaries for bottlenose dolphins. Her proposal here is based on research she conducted and reported in Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity (2011) for the Humane Society International. The proposal was originally published by CNN.com in 2013, shortly after the release of the controversial documentary Blackfish, which depicts the devastating results — to both the animals and their trainers — of keeping wild orcas in captivity.

As you read,

Think about your own experience with marine parks, zoos, and similar attractions. How did the animals you observed seem to fare in captivity?

Consider the treatment of animals trained for human entertainment. Given your own experience with animals (as a pet owner, for example), do you think some animals might enjoy performing? Why or why not?

1

T he film Blackfish compellingly describes many of the reasons why keeping orcas in captivity is — and always has been — a bad idea. The main premise of the film is that these large, intelligent, social predators are dangerous to their trainers. But orcas are also directly harmed by being confined in concrete tanks and the science is growing to support this common sense conclusion.

2

The latest data show that orcas are more than three times as likely to die at any age in captivity as they are in the wild. This translates into a shorter life span and is probably the result of several factors. First, orcas in captivity are out of shape; they are the equivalent of couch potatoes, as the largest orca tank in the world is less than one ten-

3

Yes, they may survive for years entertaining audiences, but eventually the stressors of captivity catch up to them. Very few captive orcas make it to midlife (approximately 30 years for males and 45 for females) and not one out of more than 200 held in captivity has ever come close to old age (60 for males, 80 for females). Most captive orcas die while they are still very young by wild orca standards.

4

There is a solution to both the trainer safety and orca welfare dilemmas facing marine theme parks around the world, including SeaWorld in the United States. These facilities can work with experts around the world to create sanctuaries where captive orcas can be rehabilitated and retired. These sanctuaries would be sea pens or netted-

Now even staunch SeaWorld supporters are wondering if the time has come to think outside the (concrete) box.

5

A fundamental premise of these sanctuaries, however, is that eventually they would empty. Breeding would not be allowed and captive orcas would no longer exist within the next few decades. Many wildlife sanctuaries, for circus, roadside zoo and backyard refugees, exist around the globe for animals such as big cats, elephants and chimpanzees. The business (usually nonprofit) model for these types of facilities is therefore well-

6

Creating a whale or dolphin sanctuary is not entirely theoretical. Merlin Entertainments is pursuing the establishment of the world’s first bottlenose dolphin sanctuary with Whale and Dolphin Conservation, a nonprofit environmental group. Whale and Dolphin Conservation put together a team to determine the feasibility of such a concept and the company has now identified potential sites and is studying the infrastructure that will be needed to support a group of retired dolphins.

7

Before the tragic death of SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau in 2010, the ethical arguments against keeping orcas in captivity came largely from the animal welfare/animal rights community, with the marine theme parks basically ignoring or dismissing their opponents as a vocal and out-

8

Furthermore, the marine mammal science community, which has long maintained a neutral stance on the question of whether orcas are a suitable species for captive display, has finally recognized the need to engage. An informal panel discussion on captive orcas is scheduled at the 20th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals in December, the first time this topic will be openly addressed by the world’s largest marine mammal science society.

9

The first orca was put on public display in 1964. The debate on whether that was a good idea—

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Thinking about corporate and consumer responsibility.

Rose argues that for-

What aspects of the problem seem most important: that businesses are profiting, that orcas and dolphins are highly intelligent mammals, that they are being taken out of their habitats and put into captivity, that the mammals are being trained to do tricks for our entertainment, or something else?

Thinking about animals more generally, should business ventures such as zoos, scuba diving tours, fishing boats, race tracks, and circuses — or movies that feature animals — contribute in some way to ensure the well-

being of the animals from which they profit? Reflect also on the consumer’s responsibilities in supporting businesses that profit from animals. The documentary Blackfish and Rose’s CNN.com proposal are addressed to the general public. What role, if any, do you think consumers should play?

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

A FOCUSED, WELL-

If the audience doesn’t care about the problem, or if people aren’t convinced it exists, any solution may seem too expensive or hard to implement. For this reason, proposal writers must frame the problem so that their audience will want a solution.

In his proposal, Patrick O’Malley begins by addressing his fellow students: “You got a C on the midterm . . .” (par. 1). But he knows that students are not his primary audience because the most they can do is help him pressure the real decision makers — their instructors. To convince professors that the problem is important, O’Malley uses a couple of strategies:

He addresses the intended audience:

“many professors may not realize” (par. 2)

He grabs the intended audience’s attention and enlists readers’ sympathy, using the opening scenario and rhetorical questions to remind professors what it was like to be a student:

“It’s late at night. . . .

Did you study enough? Did you study the right things?” (par. 1) He gains the audience’s respect by demonstrating that he is not just whining about a personal problem. He cites sources and establishes their reliability by identifying the researchers’ credentials and where the research was presented, and by showing that it is current:

“Reporting on recent research at Cornell University Medical School, Sian Beilock, a psychology professor at the University of Chicago. . . .” (par. 2)

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing the strategies Rose uses to frame the problem, establish its seriousness, and persuade her audience:

Based on what you can infer about the audience of CNN.com, who do you think Rose hopes to influence by publishing her proposal on that Web site? For example, does she appear to be addressing SeaWorld executives who could take action on her proposal, advertisers who could put pressure on decision makers, the general public who could boycott the theme park? What signs, if any, help you identify Rose’s intended audience and her purpose in addressing them?

Reread paragraphs 1–3. What strategies does Rose employ to convince the members of her audience that the problem is serious and they should care about it? Does Rose employ strategies like those O’Malley uses? If so, where? If not, what alternative strategies does Rose employ?

Considering Rose’s purpose and audience, how effective do you think her opening paragraphs were and what else might she have done to persuade her readers to take the problem seriously?

A WELL-

To persuade readers that more testing would help students, O’Malley makes clear in his thesis statement exactly what he wants faculty to do and why:

Proposal

Results

If professors gave brief exams at frequent intervals, students would be spurred to learn more and worry less. They would study more regularly, perform better on tests, and enhance their cognitive functioning. (par. 4)

He then cites scientific studies and news reports about scientific studies to persuade readers that the results he promises are realistic.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing Rose’s strategy to demonstrate that her proposal is feasible:

Reread paragraph 4, highlighting the sentences in which Rose spells out her proposal. What does she propose, and what does she claim the result would be if her proposal were implemented?

Now skim paragraphs 5–8. What writing strategies (such as cause-

effect reasoning, comparison and contrast, process analysis, statistics, examples) does Rose use to support her claim? Evaluate the effectiveness of the evidence Rose supplies. What other kinds of evidence would have made Rose’s proposal more convincing for you?

AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS AND ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONS: ANTICIPATING NEGATIVE SIDE EFFECTS

Effective proposals respond to readers’ potential objections. O’Malley, for example, suggests ways faculty can reduce the negative side effects of offering more low-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph evaluating how Rose responds to objections to marine sanctuaries:

Skim paragraphs 5–8. What are some of the objections that Rose implies owners of facilities like SeaWorld would make?

How effective are Rose’s suggestions for mitigating the negative effects that retiring captive orcas to sanctuaries would have on marine parks? Why do you think she claims that “this is a transformative proposal, not a punitive one” (par. 5)? Why do you think she feels the needs to reassure her audience that her proposal is “not a punitive one”? Who would care if it was?

Now skim paragraphs 7–9. If you’re not familiar with the film Rose mentions, watch the Blackfish trailer. What sort of resistance does Rose seem to be anticipating from her audience? How effective is her response?

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: CREATING UNITY

It’s important, especially in complicated proposals, to provide cues to help the audience move from paragraph to paragraph without losing sight of the main point. O’Malley, for example, provides a forecast of what his essay will cover by repeating key terms or their synonyms from his thesis statement in each of his topic sentences:

Thesis statement

If professors gave brief exams at frequent intervals, students would be spurred to learn more and worry less. They would study more regularly, perform better on tests, and enhance their cognitive functioning. (par. 2)

Topic sentence

The main reason professors should give frequent exams is that when they do and when they provide feedback to students on how well they are doing, students learn more in the course and perform better on major exams. . . .

O’Malley also uses transitions — “The main reason” (par. 4), “Another, closely related argument reason” (par. 6) — to remind readers how each paragraph relates to the thesis and to the paragraphs that precede and follow it. Writers may also use the conclusion to unify their writing by coming full circle: revisiting an idea, example, or comparison at the end of the essay that they had introduced at the beginning.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing and evaluating how Rose cues readers and creates unity:

Reread the first and last paragraphs of Rose’s essay. What idea does Rose mention in both paragraphs? How does paragraph 9 close a circle started in paragraph 1?

Now skim paragraphs 2–8, highlighting Rose’s topic sentences and any transitional words or phrases she uses.

What else might Rose have done to unify her proposal and make it easier to follow?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Representing the voiceless.

In her proposal to free captive orcas, Rose speaks for creatures that cannot speak for themselves — at least, not in English. You could propose a solution to a problem faced by those who cannot effectively advocate for themselves, perhaps because they belong to another species, do not speak the language of power, lack access to the technologies they would need to be heard, or lack the credibility or status necessary to get a fair hearing. For example, consider writing a proposal that would reduce the number of abandoned pets on campus or in the community. Or propose ways to help elderly and infirm people in your community who need transportation or elementary-