Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,” selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel.

Kelly D. Brownell

Thomas R. Frieden Ounces of Prevention — The Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages

KELLY D. BROWNELL is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke. An international expert who has published numerous books and articles, including Food Fight: The Inside Story of the Food Industry, America’s Obesity Crisis, and What We Can Do About It (2003), Brownell received the 2012 American Psychological Association Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contributions to Psychology. He was also featured in the Academy Award–nominated film Super Size Me.

THOMAS R. FRIEDEN, a physician specializing in public health, is the director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and served for several years as the health commissioner for the City of New York.

Brownell and Frieden’s proposal “Ounces of Prevention — The Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages” was originally published in 2009 in the highly respected New England Journal of Medicine, which calls itself “the most widely read, cited, and influential general medical periodical in the world.” In fact, research published there is often referred to widely throughout the media.

As you read, consider the effect that Brownell and Frieden’s use of graphs and formal citation of sources has on their credibility:

How do the graphs help establish the seriousness of the problem? How do they also help demonstrate the feasibility of the solution the authors propose?

How do the citations help persuade you to accept the authors’ solution? What effect might they have had on their original readers? (Note that the authors use neither of the two citation styles covered in Chapters 24 and 25 of this text. Instead, they use one common to medical journals and publications of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.)

Sugar, rum, and tobacco are commodities which are nowhere necessaries of life, which are become objects of almost universal consumption, and which are therefore extremely proper subjects of taxation.

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776

1

T he obesity epidemic has inspired calls for public health measures to prevent diet-

2

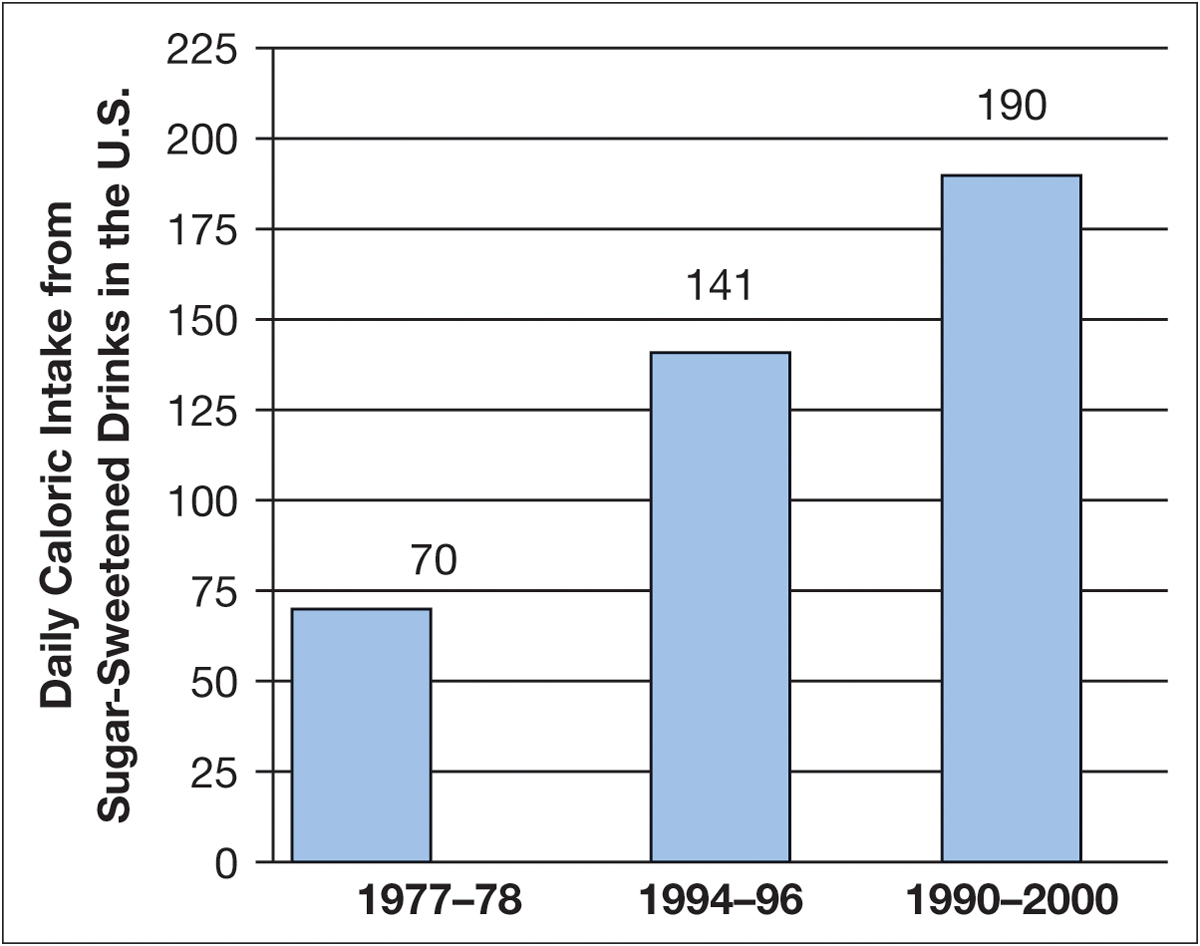

Sugar-

3

Taxes on tobacco products have been highly effective in reducing consumption, and data indicate that higher prices also reduce soda consumption. A review conducted by Yale University’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity suggested that for every 10 percent increase in price, consumption decreases by 7.8 percent. An industry trade publication reported even larger reductions: as prices of carbonated soft drinks increased by 6.8 percent, sales dropped by 7.8 percent, and as Coca-

4

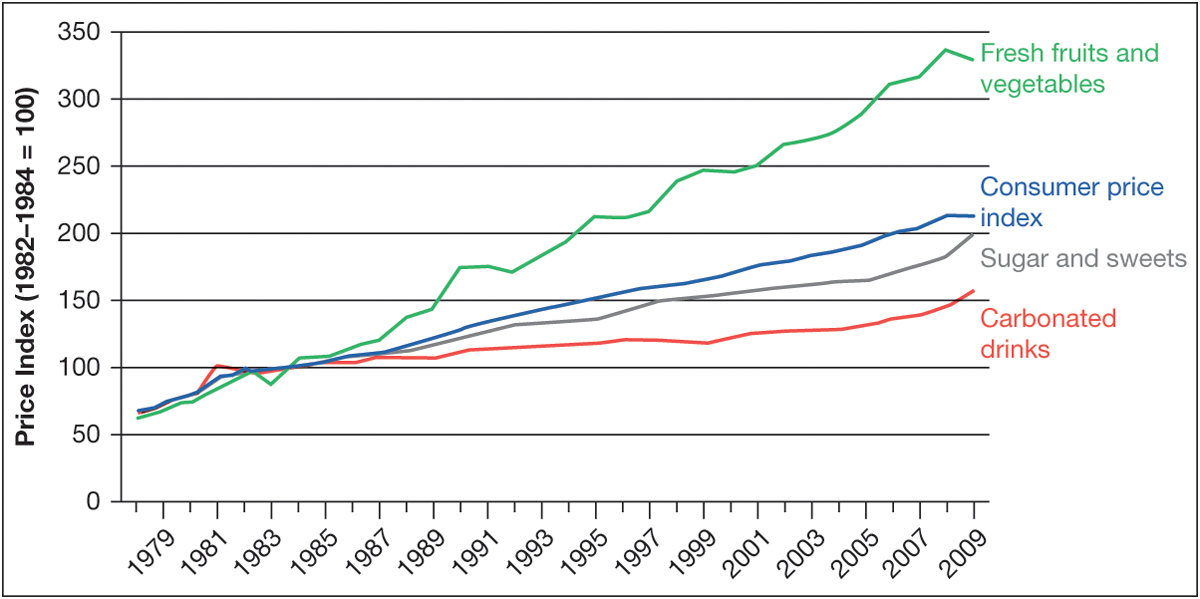

The increasing affordability of soda — and the decreasing affordability of fresh fruits and vegetables (see line graph) — probably contributes to the rise in obesity in the United States. In 2008, a group of child and health care advocates in New York proposed a one-

5

Some argue that government should not interfere in the market and that products and prices will change as consumers demand more healthful food, but several considerations support government action. The first is externality — costs to parties not directly involved in a transaction. The contribution of unhealthful diets to health care costs is already high and is increasing — an estimated $79 billion is spent annually for overweight and obesity alone — and approximately half of these costs are paid by Medicare and Medicaid, at taxpayers’ expense. Diet-

6

Objections have certainly been raised: that such a tax would be regressive, that food taxes are not comparable to tobacco or alcohol taxes because people must eat to survive, that it is unfair to single out one type of food for taxation, and that the tax will not solve the obesity problem. But the poor are disproportionately affected by diet-

7

The full impact of public policies becomes apparent only after they take effect. We can estimate changes in sugared-

8

Effects will also vary depending on whether the tax is designed to reduce consumption, generate revenue, or both; the size of the tax; whether the revenue is earmarked for programs related to nutrition and health; and where in the production and distribution chain the tax is applied. Given the heavy consumption of sugared beverages, even small taxes will generate substantial revenue, but only heftier taxes will significantly reduce consumption. Sales taxes are the most common form of food tax, but because they are levied as a percentage of the retail price, they encourage the purchase of less-

9

Although a tax on sugared beverages would have health benefits regardless of how the revenue was used, the popularity of such a proposal increases greatly if revenues are used for programs to prevent childhood obesity, such as media campaigns, facilities and programs for physical activity, and healthier food in schools. Poll results show that support of a tax on sugared beverages ranges from 37 to 72 percent; a poll of New York residents found that 52 percent supported a “soda tax,” but the number rose to 72 percent when respondents were told that the revenue would be used for obesity prevention. Perhaps the most defensible approach is to use revenue to subsidize the purchase of healthful foods. The public would then see a relationship between tax and benefit, and any regressive effects would be counteracted by the reduced costs of healthful food.

10

A penny-

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Government problem solving.

Brownell and Frieden explicitly argue in favor of the federal and/or state government taking action to address public health problems such as those related to obesity and smoking. Imposing taxes is one thing government can do. Another action is to require that foods be labeled with accurate nutritional information.

Write a few paragraphs considering the right and responsibility of government to solve public health problems. Your instructor may ask you to post your thoughts on a class discussion board or to discuss them with other students in class. Use these questions to get started:

Consider what actions government could take to address public health problems and whether government should take such actions.

Think about how you would respond to Brownell and Frieden’s argument that “though no single intervention will solve the obesity problem, that is hardly a reason to take no action” (par. 6).

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

A FOCUSED, WELL-

Brownell and Frieden in “Ounces of Prevention” identify the problem for which they are proposing a solution in broad terms as the “obesity epidemic” (par. 1). However, they frame the issue by focusing on “sugar-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing more closely how Brownell and Frieden use research to establish a causal connection between sweetened drinks and obesity:

Skim paragraph 3 to identify the findings Brownell and Frieden summarize there. Note that these are the findings of a “meta-

analysis,” which compares different studies researching the same question. Consider how effectively, if at all, these findings support Brownell and Frieden’s argument about a cause-

effect relationship between consuming sugar- sweetened beverages and obesity. Think about what kinds of studies were done and consider how Brownell and Frieden rate these different kinds of studies. Why might it be helpful for Brownell and Frieden’s readers from the New England Journal of Medicine to know the kinds of studies that have been used and which ones employ “the best methods” and get “the strongest effects”?

A WELL-

Like O’Malley, Brownell and Frieden in “Ounces of Prevention” use their title to announce the solution they are proposing: the imposition of a tax on certain beverages. They use writing strategies such as comparison-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a few paragraphs analyzing and evaluating how Brownell and Frieden use comparison and contrast as well as classification strategies to support their proposal:

Reread paragraphs 3–4. How do Brownell and Frieden use comparison and contrast there to argue for a tax on sweetened beverages?

Reread paragraphs 8–9. How do they use classification there?

Consider the strengths and weaknesses of using these two strategies to support their proposed solution. How are these two writing strategies effective ways of supporting their proposal? What other strategies might work better?

AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE TO OBJECTIONS AND ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONS: HANDLING OBJECTIONS

Proposal writers usually try to anticipate readers’ objections and questions and concede or refute them. How writers handle objections and questions affects their credibility with readers, who usually expect writers to be respectful of other points of view and to take criticism seriously while still arguing assertively for their solution. Brownell and Frieden anticipate and respond to five objections they would expect their readers to raise.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a couple of paragraphs analyzing and evaluating how Brownell and Frieden respond to objections:

Reread paragraph 5. First, summarize the objection and their argument refuting it. Then evaluate their response: How effective is their refutation likely to be with their readers?

Reread paragraph 6, in which the authors respond to a number of objections. What cues do they provide to help you follow their argument?

Given their purpose and audience, why do you think Brownell and Frieden focus so much attention on the first objection and group the other objections together in a single paragraph?

How would you describe the tone of Brownell and Frieden’s refutation? How is their credibility with readers likely to be affected by the way they respond to objections?

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: USING GRAPHS

To learn more about using graphics, see Chapter 32.

Brownell and Frieden include two graphs in their proposal — a bar graph and a line graph. Bar graphs and line graphs can be used to display numerical and statistical information at different points in time and also to compare groups or data sets by using different color bars or lines.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing and evaluating how well Brownell and Frieden integrate these graphs:

Highlight the sentences in paragraphs 2 and 4 in which Brownell and Frieden introduce each graph. How else do they integrate the graphs into their argument?

Consider the sections in which these graphs appear. How might the graphs help demarcate sections and move readers from one section to the next?

Look closely at the graphs themselves to see how the information is presented. What do the graphs contribute? Given Brownell and Frieden’s purpose and audience, why do you think they chose to include these graphs?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Improving a group to which you belong.

Consider making a proposal to improve the operation of an organization, a business, or a club to which you belong. For example, you might propose that your college keep administrative offices open in the evenings or on weekends to accommodate working students, or that a child-