Cotton Kingdom, Slave Empire

Printed Page 361

In the first half of the nineteenth century, millions of Americans migrated west. In the South, hard-driving slaveholders seeking virgin acreage for new plantations, ambitious farmers looking for patches of cheap land for small farms, striving herders and drovers pushing their hogs and cattle toward fresh pastures — everyone felt the pull of western land.

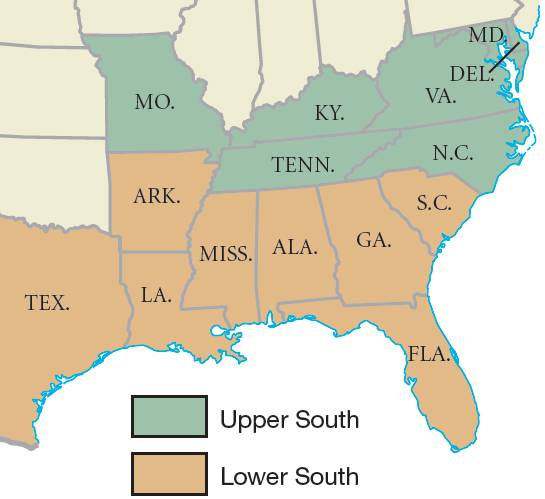

But more than anything it was cotton that propelled Southerners westward. South of the Mason-Dixon line, climate and geography were ideally suited for the cultivation of cotton. By the 1830s, cotton fields stretched from the Atlantic seaboard to central Texas. Heavy migration led to statehood for Arkansas in 1836 and for Texas and Florida in 1845. Cotton production soared to nearly 5 million bales in 1860, when the South produced three-fourths of the world’s supply. The South — especially that tier of states from South Carolina west to Texas called the Lower South — had become the cotton kingdom (Map 13.1).

A surveyors’ mark that had established the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania in colonial times. By the 1830s, the boundary divided the free North and the slave South.

A surveyors’ mark that had established the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania in colonial times. By the 1830s, the boundary divided the free North and the slave South.

Term for the South that reflected the dominance of cotton in the southern economy. Cotton was particularly important in the tier of states from South Carolina west to Texas. Cotton cultivation was the key factor in the growth of slavery.

Term for the South that reflected the dominance of cotton in the southern economy. Cotton was particularly important in the tier of states from South Carolina west to Texas. Cotton cultivation was the key factor in the growth of slavery.

The cotton kingdom was also a slave empire. The South’s cotton boom rested on the backs of slaves. As cotton agriculture expanded westward, whites shipped more than a million enslaved men, women, and children from the Atlantic coast across the continent in what has been called the “Second Middle Passage,” a massive deportation that dwarfed the transatlantic slave trade to North America. Victims of this brutal domestic slave trade marched hundreds of miles southwest to new plantations in the Lower South. Cotton, slaves, and plantations moved west together.

The slave population grew enormously. Southern slaves numbered fewer than 700,000 in 1790, about 2 million in 1830, and almost 4 million by 1860. By 1860, the South contained more slaves than all the other slave societies in the New World combined. The extraordinary growth was not the result of the importation of slaves, which the federal government outlawed in 1808. Instead, the slave population grew through natural reproduction; by midcentury, most U.S. slaves were native-born Southerners.