Burgoyne’s Army and the Battle of Saratoga

Printed Page 190

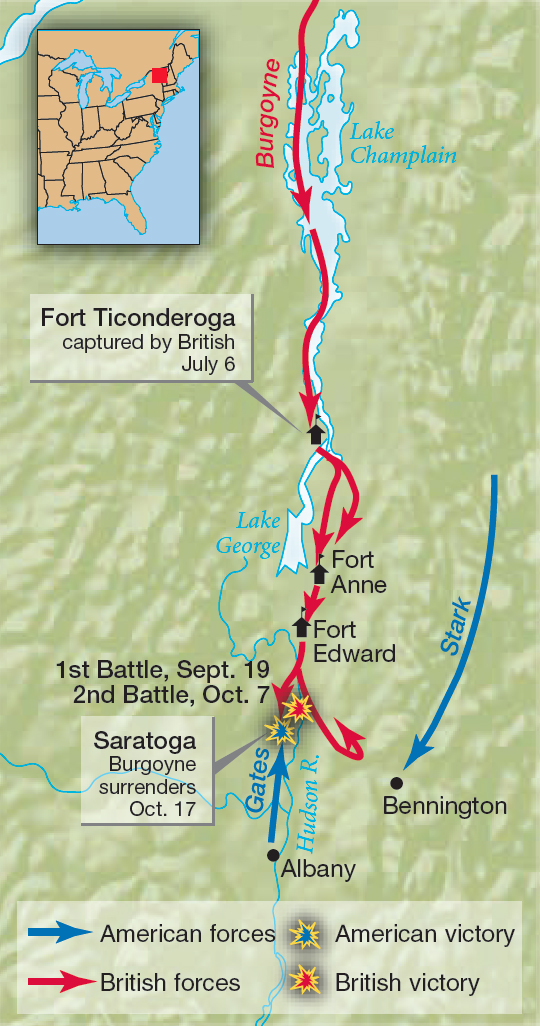

In 1777, British general John Burgoyne, commanding a considerable army, began the northern squeeze on the Hudson River valley. Coming from Canada, he marched south hoping to capture Albany, near the intersection of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers. Accompanied by 1,000 “camp followers” (cooks, laundresses, musicians) and some 400 Indian warriors, Burgoyne’s army of 7,800 men did not travel light. Food had to be packed in, not only for people but also for 400 horses hauling heavy artillery. Primitive roads through dense forests slowed their progress to a crawl.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

Why did Americans wait so long before they declared their independence?

What initial challenges did the opposing armies face?

What role did the home front play in the war?

How were Native Americans and the French involved in the war?

Why did the British southern strategy ultimately fail?

Conclusion: Why did the British lose the American Revolution?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

The logical second step in isolating New England should have been to advance troops up the Hudson from New York City to meet Burgoyne. American surveillance indicated that General Howe in Manhattan was readying his men for a major move in August 1777. But Howe surprised everyone by sailing south to attack Philadelphia.

To reinforce Burgoyne, British and Hessian troops from Montreal came from the east along the Mohawk River, aided by Mohawks and Senecas of the Iroquois Confederacy. The British were counting on loyalism among the numerous German colonists living in the Mohawk Valley. A hundred miles west of Albany, they encountered American Continental soldiers at Fort Stanwix and laid siege, causing local German militiamen and a small number of Oneida Indians to rush to the Continentals’ support. Mohawk chief Joseph Brant led the Senecas and Mohawks in an ambush on the German Americans and the Oneidas in a narrow ravine called Oriskany, killing nearly 500 out of 840 of them. On Brant’s side, some 90 warriors were killed. The defenders of Fort Stanwix ultimately repelled their attackers. These deadly battles of Oriskany and Fort Stanwix were also complexly multiethnic, pitting Indians against Indians, German Americans against German mercenaries, New York patriots against New York loyalists, and English Americans against British soldiers.

A punishing defeat for Americans in a ravine named Oriskany near Fort Stanwix in New York in August 1777. Mohawk and Seneca Indians ambushed German American militiamen aided by allied Oneida warriors, and 500 on the Revolutionary side were killed.

A punishing defeat for Americans in a ravine named Oriskany near Fort Stanwix in New York in August 1777. Mohawk and Seneca Indians ambushed German American militiamen aided by allied Oneida warriors, and 500 on the Revolutionary side were killed.

The British retreat at Fort Stanwix deprived General Burgoyne of the additional troops he expected. Camped at a small village called Saratoga, he was isolated, with food supplies dwindling and men deserting. His adversary at Albany, General Horatio Gates, began moving his army toward Saratoga. Burgoyne decided to attack first, and the British prevailed, but at the great cost of 600 dead or wounded. Three weeks later, an American attack on Burgoyne’s forces in the second stage of the battle of Saratoga cost the British another 600 men and most of their cannons. General Burgoyne finally surrendered to the American forces on October 17, 1777.

A two-stage battle in New York ending with the decisive defeat and surrender of British general John Burgoyne on October 17, 1777. This victory convinced France to throw its official support to the American side in the war.

A two-stage battle in New York ending with the decisive defeat and surrender of British general John Burgoyne on October 17, 1777. This victory convinced France to throw its official support to the American side in the war.

General Howe, meanwhile, had succeeded in occupying Philadelphia in September 1777. Figuring that the Saratoga loss was balanced by the capture of Philadelphia, the British government proposed a negotiated settlement — not including independence — to end the war. The American side refused.

But supplies of arms and food ran precariously low. Washington moved his troops into winter quarters at Valley Forge, just west of Philadelphia. Quartered in drafty huts, the men lacked blankets, boots, stockings, and food. Some 2,000 men at Valley Forge died of disease; another 2,000 deserted over the bitter six-month encampment.

Washington blamed the citizenry for lack of support; indeed, evidence of corruption and profiteering was abundant. Army suppliers too often provided defective food, clothing, and gunpowder. One shipment of bedding arrived with blankets one-quarter their customary size. Food supplies arrived rotten. As one Continental officer said, “The people at home are destroying the Army by their conduct much faster than Howe and all his army can possibly do by fighting us.”