The Louisiana Purchase

In 1763, at the end of the Seven Years’ War, a large area west of the United States shifted from France to Spain, but Spain never effectively controlled it (see “The War and Its Consequences” in chapter 6). Centered on the Great Plains, it was home to Indian tribes, most notably the powerful and expansionist Comanche nation. New Orleans was Spain’s principal stronghold, a city of French origins and population, strategically sited on the Mississippi River near its outlet to the Gulf of Mexico. Spain profited modestly from trade taxes it imposed on the small flow of agricultural products shipped down the river from American farms in the western parts of Kentucky and Tennessee.

Spanish officials in New Orleans and St. Louis (another city of French origins) worried that their sparse population could not withstand an anticipated westward movement of Americans. At first they hoped for a Spanish-Indian alliance to halt the expected demographic wave, but defending many hundreds of miles along the Mississippi River against Americans on the move was a daunting prospect. Thus, in 1800 Spain struck a secret deal to return this trans-Mississippi territory to France, in the hopes that a French Louisiana would provide a buffer zone between Spain’s more valuable holdings in northern Mexico and the land-hungry Americans. The French emperor Napoleon accepted the transfer and agreed to Spain’s condition that France could not sell Louisiana to anyone without Spain’s permission.

> UNDERSTAND

POINTS OF VIEW

Why was Thomas Jefferson so alarmed by the prospect of France’s control of the Louisiana Territory?

From the U.S. perspective, Spain had proved a weak western neighbor, but France was another story. Jefferson was so alarmed by the rumored transfer that he instructed Robert R. Livingston, America’s minister in France, to try to buy New Orleans. When Livingston hinted that the United States might seize it if buying was not an option, the French negotiator asked him to name his price for the entire Louisiana Territory from the Gulf of Mexico north to Canada. Livingston shrewdly stalled and within days accepted the bargain price of $15 million (Map 10.2).

On the verge of war with Britain, France needed both money and friendly neutrality from the United States, and it got both from the quick sale of the Louisiana Territory. In addition, the recent and costly loss of Haiti as a colony made a French presence in New Orleans less feasible as well. But in selling Louisiana to the United States, France had broken its agreement with Spain, which protested that the sale was illegal.

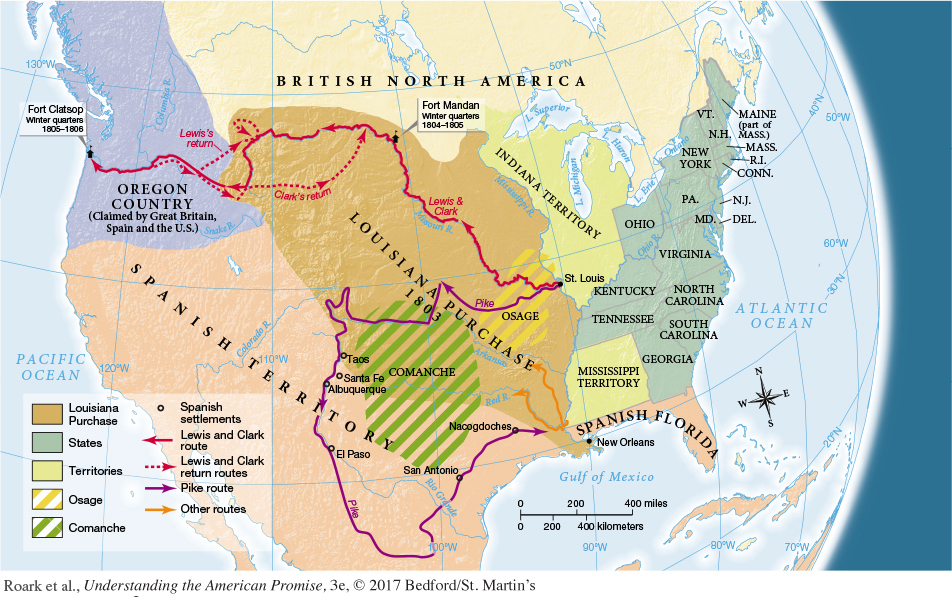

Moreover, there was no clarity on the western border of this land transfer. Spain claimed that the border was about one hundred miles west of the Mississippi River, while in Jefferson’s eyes it was some eight hundred miles farther west, defined by the crest of the Rocky Mountains. When Livingston pressured the French negotiator to clarify his country’s understanding of the boundary, the negotiator replied, “I can give you no direction. You have made a noble bargain for yourself, and I suppose you will make the most of it.” [[LP Map: M10.02 Jefferson’s Expeditions in the West, 1804–1806 – MAP ACTIVITY/

Jefferson gained congressional approval for the Louisiana Purchase, but without the votes of Federalist New England, which feared that such a large acquisition of land would be detrimental to Federalist Party strength. In late 1803, the American army took formal control of the Louisiana Territory, and the United States nearly doubled in size—at least on paper.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 258

Section Chronology