Introduction for Chapter 10

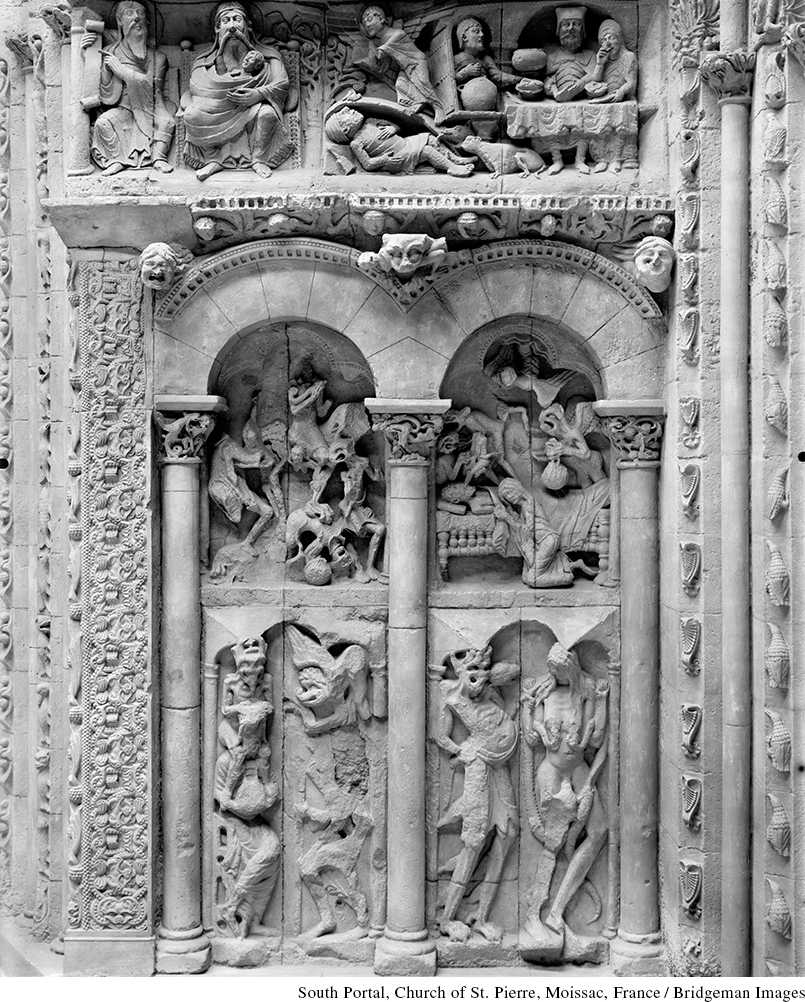

A BIT AFTER THE YEAR 1100, sculptors were hired to decorate the inner walls of the cloister porch at Moissac, a monastery in southern France. For one wall they depicted the New Testament story of the poor man Lazarus and the rich man Dives. Their fates could not have been more different. While the soul of Lazarus was carried to heaven by an angel, the rich man was shown plunging down to hell.

The sculptor’s work reflected a widespread change in attitude toward money. In the Carolingian and post-Carolingian period (up to, say, 1050), people generally considered wealth a very good thing. Rich kings were praised for their generosity; expensively produced manuscripts, illuminated with gold leaf and precious colors, were highly prized; and splendid churches like Charlemagne’s chapel at Aachen were widely admired. Such views changed over the course of the eleventh century.

The most striking feature of the period from 1050 to 1150 was the rise of a money economy in western Europe. Agricultural production swelled, fueling the growth of trade and the expansion of cities. A new class of well-heeled merchants, bankers, and entrepreneurs emerged. These developments were met with a wide variety of responses. Some people fled the cities and their new wealth altogether, seeking isolation and poverty. Others, even the participants in the new economy, condemned it and emphasized its corrupting influence. Many people, however, embraced the new money economy.

CHAPTER FOCUS How did the commercial revolution affect religion and politics?

The development of a profit-based economy quickly transformed the landscape and lifestyles of western Europe. Many villages and fortifications became cities where traders, merchants, and artisans conducted business. In some places, town dwellers began to determine their own laws and administer their own justice. Although most people still lived in sparsely populated rural areas, the new cash economy touched their lives in many ways. Economic concerns helped drive changes within the church, where a movement for reform gathered steam and exploded in three directions: the Investiture Conflict, new monastic orders emphasizing poverty, and the crusades. Money allowed popes, kings, and princes to redefine the nature of their power.