England under Norman Rule

England under Norman Rule

In the twelfth century, the kings of England were the most powerful monarchs of Europe, in large part because they ruled their whole kingdom by right of conquest. When the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) died childless in 1066, three main contenders vied for the English throne: Harold, earl of Wessex, an Englishman close to the king but not of royal blood; Harald Hardrada, the king of Norway, who had unsuccessfully attempted to conquer the Danes and now turned hopefully to England; and William, duke of Normandy, who claimed that Edward had promised him the throne fifteen years earlier. On his deathbed, Edward had named Harold of Wessex to succeed him, and a royal advisory committee that had the right to choose the king had confirmed the nomination. When he learned that Harold had been anointed and crowned, William (1027–1087) prepared for battle. Appealing to the pope, he received the banner of St. Peter and with this symbol of God’s approval launched the invasion of England, filling his ships with warriors recruited from many parts of France. Just before William’s invasion force landed, Harold defeated Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, near York, in the north of England. When he heard of William’s arrival, Harold turned his forces south, marching them 250 miles and picking up new soldiers along the way to meet the Normans.

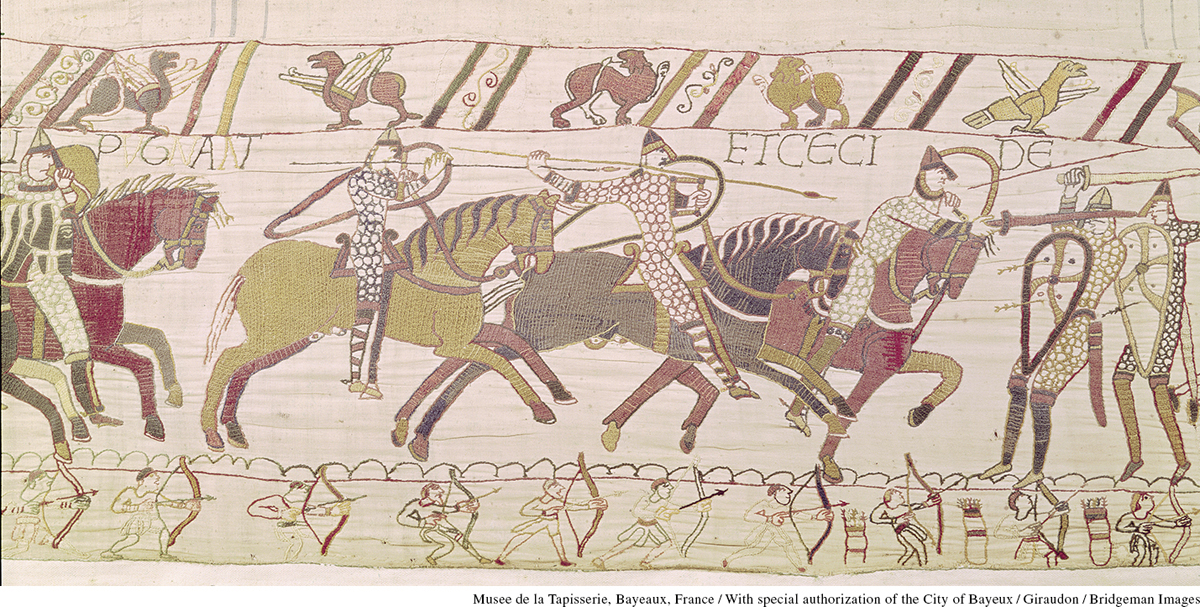

The two armies clashed at the battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, in one of history’s rare decisive battles. Most of Harold’s men were on foot, armed with battle-axes and stones tied to sticks, which could be thrown with great force. William’s army consisted of perhaps three thousand mounted knights, a thousand archers, and the rest infantry. At first William’s knights broke rank, frightened by the deadly battle-axes thrown by the English; but then some of the English also broke rank as they pursued the knights. Gradually Harold’s troops were worn down, particularly by William’s archers, whose arrows flew a hundred yards, much farther than an Englishman could throw his battle-ax. (Some of the archers are depicted on the lower margin of the Bayeux “Tapestry.”) By dusk, King Harold was dead and his army defeated.

Some Anglo-Saxons in England supported William. But William—known to posterity as William the Conqueror—wanted to replace, not assimilate, the Anglo-Saxons. During William’s reign, families from the European continent almost totally supplanted the English aristocracy. Although the English peasantry remained—now with new lords—many of them “perished . . . by famine or the sword,” as William confessed on his deathbed. Modern historians estimate that one out of five people in England died as a result of the Norman conquest and its immediate aftermath. (See “Document 10.2: Opposition to the Norman Conquest.”) Yet, although the Normans destroyed a generation of English men and women, they preserved and extended many Anglo-Saxon institutions. For example, the new kings retained the old administrative divisions and legal system of the shires. At the same time, they drew from continental institutions. They set up a political hierarchy, culminating in the king, whose strength was reinforced by his castles. Because all of England was the king’s by conquest, he could treat it as his booty; William kept about 20 percent of the land for himself and divided the rest, distributing it in large but scattered fiefs to a relatively small number of his barons and family members, lay and ecclesiastical, as well as to some lesser men. In turn, these fief-holders maintained their own vassals; they owed the king military service—and the service of a fixed number of their vassals—along with certain dues, such as reliefs (money paid upon inheriting a fief) and aids (payments made on important occasions).

In addition to these revenues from the nobles, the king of England made sure that he would get his share from the peasantry. In 1086, William ordered a survey and census of England, popularly called Domesday because, like the reckoning Christians expected at doomsday, it provided facts that could not be appealed. It was the most extensive inventory of land, livestock, taxes, and population that had ever been compiled in Europe. The king’s men consulted Anglo-Saxon tax lists and took testimony from local men. From these inquests, scribes drew up reports, which were then summarized in Domesday itself. (See “Taking Measure: English Livestock in 1086.”)

William was not just the ruler of England; he was also duke of Normandy. The Norman conquest tied England to the languages, politics, institutions, and culture of the European continent. English commerce was linked to the wool industry in Flanders. St. Anselm, the archbishop of Canterbury and author of Why God Became Man, was born in Italy and served as the abbot of a monastery in Normandy before crossing the Channel to England. Modern English is an amalgam of Anglo-Saxon and Norman French.

The barons of England retained their estates in Normandy and elsewhere, and the kings of England often spent more time on the continent than they did on the island. When William’s son Henry I (r. 1100–1135) died without male heirs, civil war soon erupted: the throne of England was fought over by two French counts, one married to Henry’s daughter, the other to his sister. The story of England after 1066 was, in miniature, the story of Europe.