Fairs, Towns, and Cities

Fairs, Towns, and Cities

The commercial revolution took place in three venues: markets, fairs, and permanent centers. In some places, markets met weekly to sell local surplus goods. In others, fairs—which lasted anywhere from several days to a few months—took place once a year and drew traders from longer distances. Some fairs specialized in particular goods: at Saint-Denis, a monastery near Paris that had had a fair since at least the seventh century, the star attraction was wine. Most fairs offered a wide variety of products: at the Champagne fairs in France, there were woolen fabrics from Flanders; silks from Lucca, Italy; leather goods from Spain; and furs from Germany. Bankers attended as well, exchanging coins from one currency into another—and charging for their services. Local inhabitants did not have to pay taxes or tolls, but traders from the outside—protected by guarantees of safe conduct—were charged stall fees as well as entry and exit fees. Local landlords reaped great profits, and as the fairs came under royal control, kings did so as well. (See “Document 10.1: Peppercorns as Money.”)

Permanent commercial centers (cities and towns) developed around castles and monasteries and within the walls of ancient Roman towns. Great lords in the countryside—and this included monasteries—were eager to take advantage of the profits that their estates generated. In the late tenth century, they reorganized their lands for greater productivity, encouraged their peasants to cultivate new land, and converted services and dues to money payments. With ready cash, they not only fostered the development of local markets and yearly fairs, where they could sell their surpluses and buy luxury goods, but also encouraged traders and craftspeople to settle down near them.

Some markets formed just outside the walls of older cities; these gradually merged into new and enlarged urban communities as towns built new walls around them to protect their inhabitants. Along the Rhine River and in other river valleys, cities sprang up to service the merchants who traversed the route between Italy and the north. Many long-distance traders were Italians and Jews. They supplied the fine wines, spices, and fabrics beloved by lords and ladies, their families, and their vassals. Italians took up long-distance trade because of Italy’s proximity to Byzantine and Islamic ports, their opportunities for plunder and trade on the high seas, and their never entirely extinguished urban traditions.

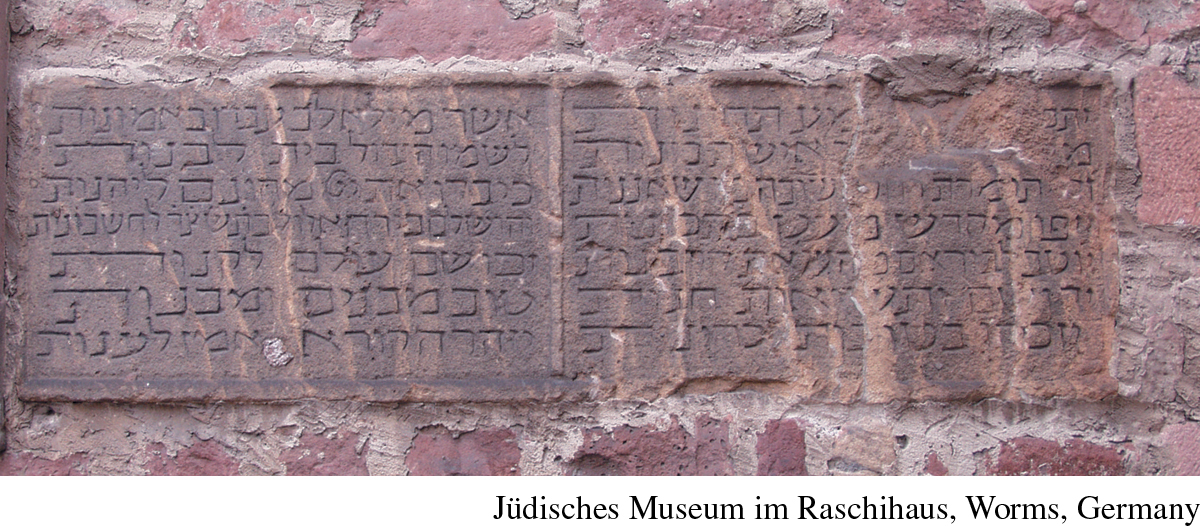

The Jews of Mediterranean regions—especially Italy and Spain—had been involved in commerce since Roman times. That trade had centered on the Mediterranean; now it extended to the north as well. For Jews living in the port cities of the old Roman Empire, little had changed. But for many Jews in northern Europe, the story was different. They had settled on the land alongside other peasants, and during the Carolingian period their properties bordered those of their Christian neighbors. As political power fragmented over the course of the tenth century and the countryside was reorganized under local lords, many Jews were driven off the land. They found refuge in the new towns and cities. Some became scholars, doctors, and judges within their communities; many became small-time pawnbrokers; and still others became moneylenders and financiers.

By the eleventh century, most Jews lived in cities but were not citizens. They were generally serfs of the king or, in the Rhineland, under the safeguard of the local bishop. This status was ambiguous: the Jews were “protected” but also exploited since their protectors constantly demanded steep taxes. Regular town trade groups, craft organizations, and town governments often rested on a conception of the common good sealed by an oath among Christians—and thus, by definition, excluded Jews.

Nevertheless, Jews had their own institutions, centered on the synagogue, their place of worship. Although they often lived in a “Jewish quarter,” they were not forcibly segregated from other townspeople. In many cities they lived near Christians, purchased products from Christian craftspeople, and hired Christians as servants. In turn, Christians purchased luxury goods from Jewish long-distance traders and often borrowed money from Jewish lenders. The fact that Jews and Christians could live side by side had less to do with tolerance than with lack of planning. Most towns in medieval Europe grew haphazardly. Typically, towns had a center, where the church and town government had their headquarters, and around this were the shops of tradespeople and craftspeople, generally grouped by specialty: butchers, for example, lived and worked on the Street of the Butchers.

The look and feel of such developing cities varied enormously, but nearly all included a marketplace, a castle, and several churches. The streets—made of packed clay or gravel—were often narrow, dirty, dark, and winding. Most people had to adapt to increasingly crowded conditions. Even so, most city dwellers tended a garden and perhaps livestock as well, living largely off the food they raised themselves.

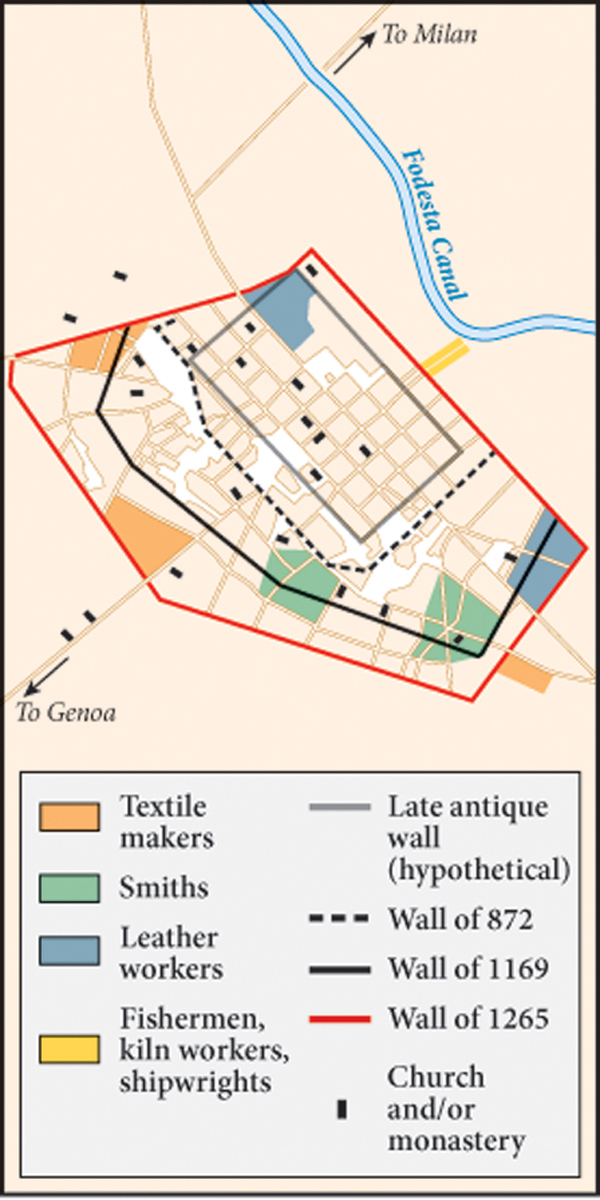

Cities were part of a building boom. Towns put up specialized buildings for trade and for city government, charitable houses for the sick and indigent, city halls, and warehouses. They also expanded their walls. Workers at Piacenza, for example, first pulled down the late antique wall and replaced it with a more extensive one in 872. Then, in 1169, Piacenzans took down the ninth-century wall and replaced it with one that was still more expansive.

Before the eleventh century, Europeans had depended on boats and waterways for bulky long-distance transport. In the twelfth century, carts could haul items overland because new roads through the countryside linked the urban markets and strengthened governments could protect overland travelers. Still, although commercial centers developed throughout western Europe, they grew fastest and most densely in regions along key waterways: the Mediterranean coasts of Italy, France, and Spain; northern Italy along the Po River; the Rhône-Saône-Meuse river system; the Rhineland; the English Channel; the shores of the Baltic Sea. During the eleventh century, these waterways became part of a single interdependent economy.

What did townspeople look like? We can get an idea from a twelfth-century baptismal font cast in Liège. It shows Jesus speaking to the soldiers and publicans (tax collectors): the soldier is dressed as a medieval knight, while the publicans wear the caps and clothes of well-to-do city dwellers.