The Arts

The Arts

The lure of the classical past was as strong in the visual arts as in literature—and for many of the same reasons. Architects and artists admired ancient Athens and Rome, but they also modified these classical models, melding them with medieval artistic traditions.

The Florentine architect Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) looked at the unplanned medieval city with dismay. He proposed that each building in a city be proportioned to fit harmoniously with all the others and that city spaces allow for all necessary public activities—there should be market squares, play areas, grounds for military exercises. In Renaissance cities, the agora and the forum (the open, public spaces of the classical world) appeared once again, but in a new guise: the piazza—a plaza or open square. Architects carved out spaces around their new buildings, and they rimmed them with porticoes—graceful covered walkways of columns and arches.

The Gothic cathedral of the Middle Ages was a cluster of graceful spikes and soaring arches. While Renaissance architects appreciated its vigor and energy, they tamed it with regular geometrical forms inspired by classical buildings. Classical forms were applied to previously built structures as well as new ones. Florence’s Santa Maria Novella, for example, had been a typical Gothic church when it was first built. But when Alberti, the man who believed in public spaces and harmonious buildings, was commissioned to replace its facade, he drew on Roman temple forms. (See “Seeing History: Façades from Gothic to Renaissance.”)

The classical world inspired artists as well. This explains the style Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378?–1455) chose when he competed to produce the doors of Florence’s baptistery in 1400. His entry showed the sacrifice of Isaac from the Old Testament: the young, nude Isaac was modeled on the masculine ideal of ancient Greek sculpture. At the same time, Ghiberti drew on medieval models for his depiction of Abraham and for his quatrefoil frame. In this way, he gracefully melded old and new elements—and won the contest.

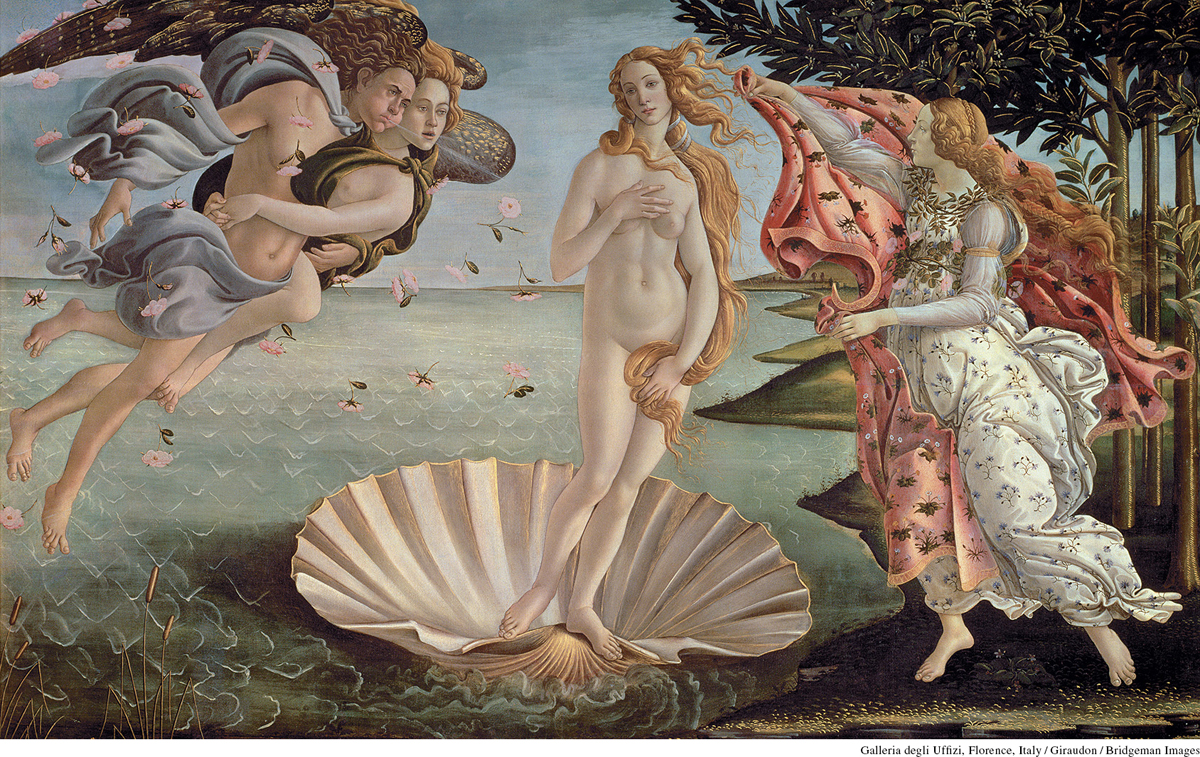

In addition to using the forms of classical art, Renaissance artists also mined the ancient world for new subjects. Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, had numerous stories attached to her name. At first glance, The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445–1510) seems simply an illustration of the tale of Venus’s rise from the sea. A closer look, however, shows that Botticelli borrowed from the poetry of Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494), who wrote of “fair Venus, mother of the cupids”:

Zephyr bathes the meadow with dew

spreading a thousand lovely fragrances:

wherever he flies he clothes the countryside

in roses, lilies, violets, and other flowers.

In Botticelli’s painting, Zephyr—one of the winds—blows while Venus herself is about to be clothed in a fine robe embroidered with leaves and flowers.

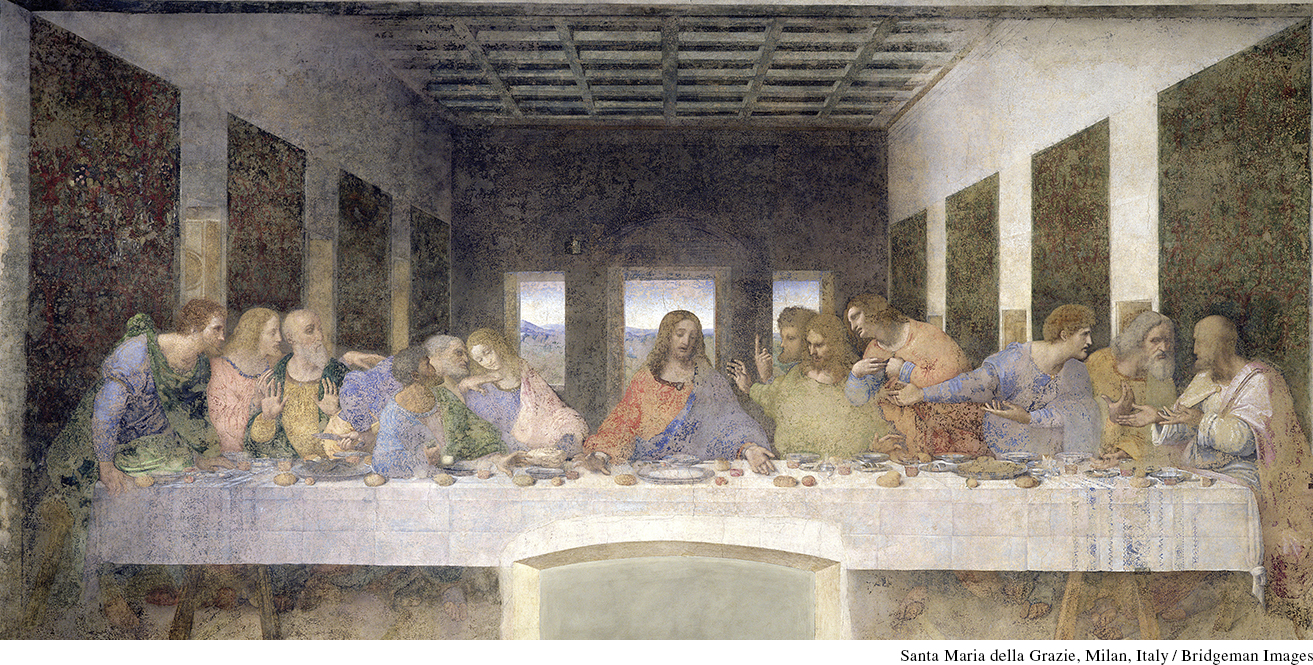

The Sacrifice of Isaac and The Birth of Venus show some of the ways in which Renaissance artists used ancient models. Other Renaissance artists perfected perspective—the illusion of three-dimensional space—to a degree that even classical antiquity had not anticipated. The development of the laws of perspective accompanied the introduction of long-range weaponry, such as cannons. In fact, some of perspective’s practitioners—Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), for example—were military engineers as well as artists. In Leonardo’s painting The Last Supper, sight lines meet at a point somewhere beyond the back windows while opening wide at the table. In this way the entire hall becomes a frame to accentuate the figure of Christ.

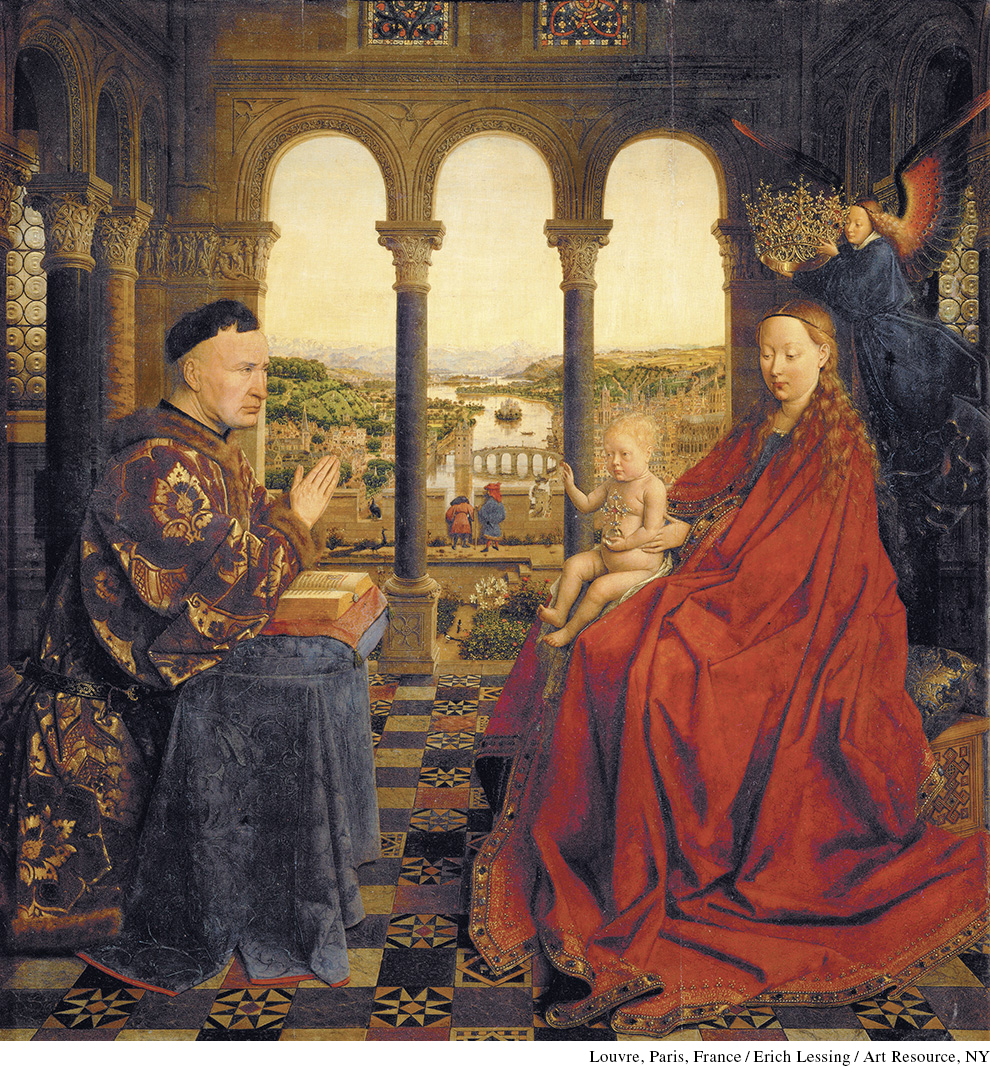

Ghiberti, Botticelli, and Leonardo were all Italian artists. While they were creating their works, a northern Renaissance was taking place as well. At the court of Burgundy during the Hundred Years’ War, the dukes commissioned portraits of themselves—sometimes unflattering ones—just as Roman leaders had once commissioned their own busts. Soon it was the fashion for those who could afford it to have a portrait made, showing them as naturalistically as possible. Around 1433, the chancellor Nicolas Rolin, for example, commissioned the Dutch artist Jan van Eyck to paint his portrait. Though opposite the Virgin and the baby Jesus, Rolin, in a pious pose, is the key figure in the picture. The grand view of a city behind the figures was meant to underscore Rolin’s prominence in the community. In fact Rolin was an important man: he worked for the duke of Burgundy and was also the founder of a hospital at Beaune and a religious order of nurses to serve it. Van Eyck’s portrait emphasized not only Rolin’s dignity and status but also his individuality. The artist took pains to show even the wrinkles of his neck and the furrows on his brow.

In music, Renaissance composers incorporated classical texts and allusions into songs that were based on the motet and other forms of polyphony. Working for patrons—whether churchmen, secular rulers, or republican governments—they expressed the glory, religious piety, and prestige of their benefactors. In fact, Renaissance rulers spent as much as 6 percent of their annual revenue to support musicians and composers.

Every proper court had its own musicians. Some served as chaplains, writing music for the ruler’s private chapel—the place where his court and household heard Mass. When Josquin Desprez (1440–1521) served as the duke of Ferrara’s chaplain, he wrote a Mass that used the musical equivalents of the letters of the duke’s name (the Italian version of do re mi) as its theme. Isabella d’Este (1474–1539), the daughter of the duke, employed her own musicians—singers, woodwind and string players, percussionists, and keyboard players—while her husband, the duke of Mantua, had his own band. Humanism and music came together: because Isabella loved Petrarch’s poems, she had the composer Bartolomeo Tromboncino set them to music.

The church, too, was a major sponsor of music. Every feast required music, and the papal schism inadvertently encouraged more musical production than usual, as rival popes tried to best one another in the realm of pageantry and sound. Churches needed choirs of singers, and many choirboys went on to become composers, while others sang well into adulthood: in the fourteenth century, the men who sang in the choir at Reims received a yearly stipend and an extra fee every time they sang the Mass and the liturgical offices of the day.

REVIEW QUESTION How and why did Renaissance humanists, artists, and musicians revive classical traditions?

When the composer Johannes Ockeghem—chaplain for three French kings—died in 1497, his fellow musicians vied in expressing their grief in song. Josquin Desprez was among them, and his composition illustrates how the addition of classical elements to traditional musical forms enhanced music’s emotive power. Josquin’s work combines personal grief with religious liturgy and the feelings expressed in classical elegies. The piece uses five voices. Inspired by classical mythology, four of the voices sing in the vernacular French about the “nymphs of the wood” coming together to mourn. But the fifth voice intones the words of the liturgy: Requiescat in pace (“May he rest in peace”). At the very moment in the song that the four vernacular voices lament Ockeghem’s burial in the dark ground, the liturgical voice sings of the heavenly light. The contrast makes the song more moving. By drawing on the classical past, Renaissance musicians found new ways in which to express emotion.