The Hundred Years’ War, 1337–1453

The Hundred Years’ War, 1337–1453

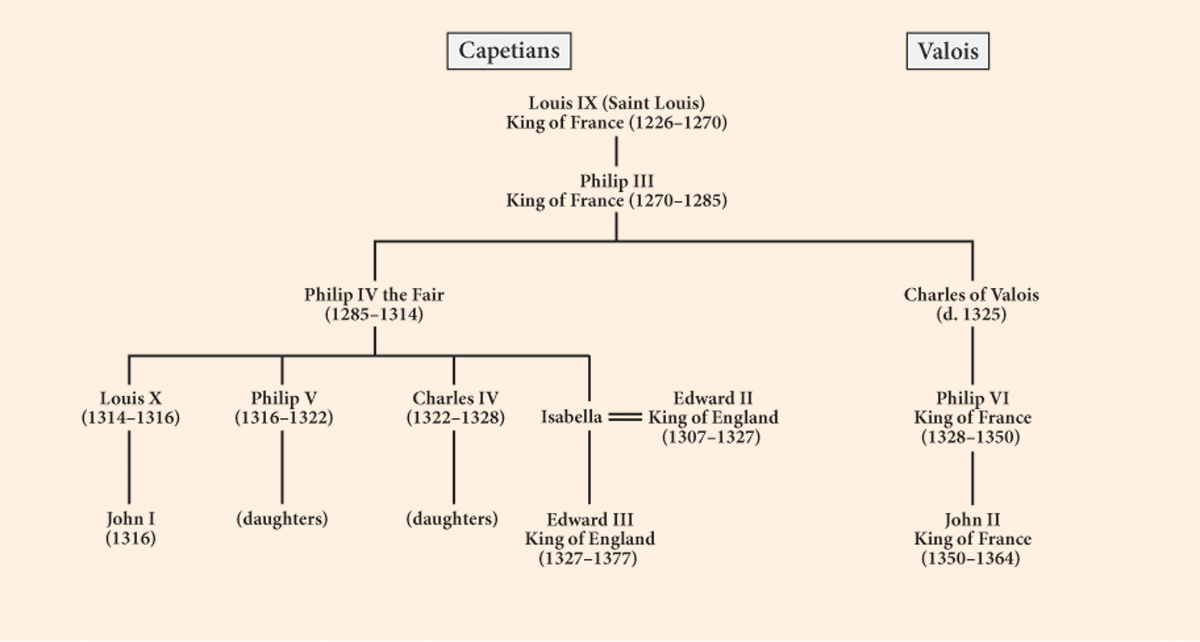

Adding to people’s miseries during the Black Death were the ravages of war. One of the most brutal was the Hundred Years’ War, which pitted England against France. Since the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the king of England had held land on the continent. The French kings continually chipped away at it, however, and by the beginning of the fourteenth century England retained only the area around Bordeaux, called Guyenne. In 1337, after a series of challenges and skirmishes, King Philip VI of France (whose dynasty, the Valois, took over when the Capetians had no male heir) declared Guyenne to be his. In turn, King Edward III of England, son of Philip the Fair’s daughter, declared himself king of France (Figure 13.1). The Hundred Years’ War had begun.

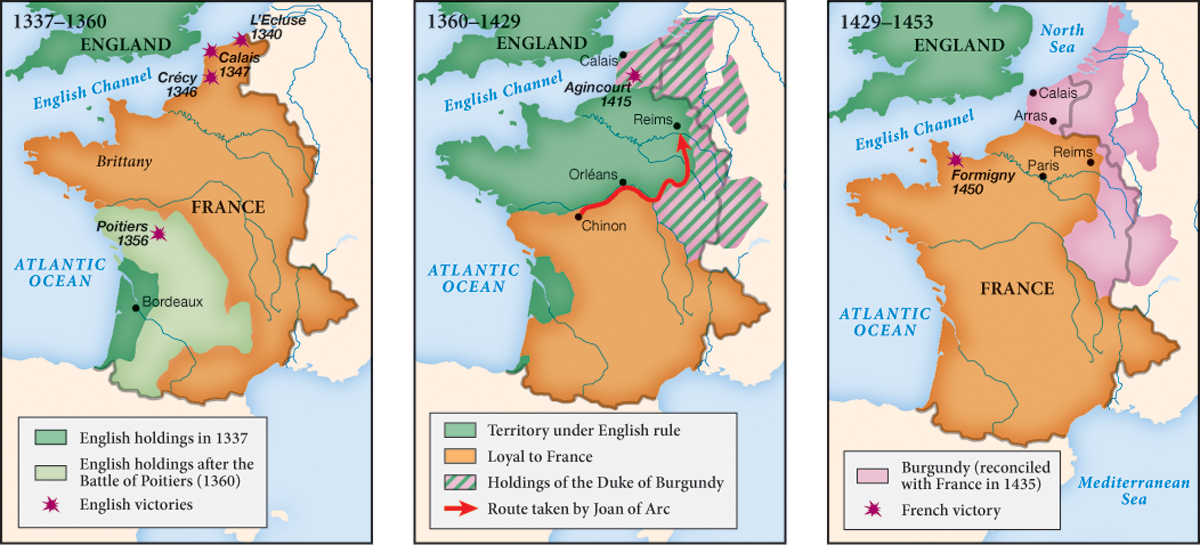

The war had two major phases. In the first, the English gained ground, and a new political entity, the duchy of Burgundy, allied itself with England. This phase culminated in 1415, when the English achieved a great victory at the battle of Agincourt and took over northern France. In the second phase, however, fortunes reversed entirely after a sixteen-year-old peasant girl inspired the dauphin (the yet-uncrowned heir to the throne) and his troops. Prompted by visions in which God told her to lead the war against the English, and calling herself “the Maid” (a virgin), Joan of Arc (1412–1431) arrived at court in 1429 wearing armor, riding a horse, and leading a small army. Full of charisma and confidence at a desperate hour, Joan convinced the French that she had been sent by God when she fought courageously (and was wounded) in the successful battle of Orléans. Soon, with Joan at his side, the dauphin traveled deep into enemy territory to be anointed and crowned as King Charles VII at the cathedral in Reims, following the tradition of French monarchs. Joan was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, and put to death by her purchasers (Map 13.2). (See “Contrasting Views: Joan of Arc: Who Was ‘the Maid’?”)

As it unfolded, the Hundred Years’ War drew people from much of Europe into its vortex. Both the English and the French hired mercenaries from Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands; the best crossbowmen came from Genoa.

The duchy of Burgundy became involved in the war when the marriage of the heiress to Flanders and the duke of Burgundy in 1369 created a powerful new state. Calculating shrewdly which side—England or France—to support and cannily entering the fray when it suited them, the dukes of Burgundy created a glittering court, a center of art and culture. Had Burgundy maintained its alliance with England, the map of Europe would be entirely different today. But, sensing France’s new strength, the duke of Burgundy broke off with England in 1435. The duchy continued to prosper until its expansionist policies led to the formation of a coalition against it. The last duke, Charles the Bold, died fighting in 1477. His daughter, his only heir, tried to save Burgundy by marrying the Holy Roman Emperor, but the move was to little avail. The duchy broke up, with France absorbing its western bits.

Flanders, too, got drawn into the war. Its cities depended on England for the raw wool that they turned into cloth. This is why, at the beginning of the war, Flemish townsmen allied with England against their count, who supported the French king. But discord among the cities and within each town soon ended the rebellion. Although revolts continued to flare up, the count thereafter allowed a measure of self-government to the towns, maintained some distance from French influence, and managed on the whole to keep the peace.

The nature of warfare changed during the Hundred Years’ War. At its start, the chronicler Jean Froissart (d. c. 1405) considered it a chivalric adventure, expecting it to display the gallantry and bravery of the medieval nobility. But even Froissart could not help but notice that most of the men who went to battle were not wealthy nobles and knights. They were not even ordinary foot soldiers, who previously had made up a large portion of all medieval armies. The soldiers of the Hundred Years’ War were primarily mercenaries: men who fought for pay and plunder, heedless of the king for whom they were supposed to be fighting. During lulls in the war, these so-called Free Companies lived off the French countryside, terrorizing the peasants and exacting “protection” money.

The ideal chivalric knight fought on horseback with other armed horsemen. But in the Hundred Years’ War, foot soldiers and archers were far more important than swordsmen. The French tended to use crossbows, whose heavy, deadly arrows were released by a mechanism that even a townsman could master. The English employed longbows, which could shoot five arrows for every one launched on the crossbow. Meanwhile, gunpowder was slowly being introduced and cannons forged. Handguns were beginning to be used, their effect about equal to that of crossbows.

By the end of the war, chivalry was only a dream—though one that continued to inspire soldiers even up to the First World War. Heavy artillery and foot soldiers, tightly massed together in formations of many thousands of men, were the face of the new military. Moreover, the army was becoming more professional and centralized. In the 1440s, the French king created a permanent army of mounted soldiers. He paid them a wage and subjected them to regular inspection.

In addition to changing the face of warfare, the Hundred Years’ War gave a new voice—however temporary—to the lower classes in France and England. When the English captured the French king John at the battle of Poitiers in 1356, Étienne Marcel, provost of the Paris merchants, and other disillusioned members of the estates of France (the representatives of the clergy, nobility, and commons) met to discuss political reform, the incompetence of the French army, and the high taxes they paid to finance the war. Under Marcel’s leadership, a crowd of Parisians killed some nobles and for a short while took control of the city. But troops soon blockaded Paris and cut off its food supply. Later that year, Marcel was assassinated and the Parisian revolt came to an end.

In the same year, peasants weary of the Free Companies (who were ravaging the countryside) and disgusted by the military incompetence of the nobility rose up in protest. The French nobility called the peasant rebellion the Jacquerie, probably taken from a derisive name for male peasants: Jacques Bonhomme (“Jack Goodfellow”). The peasants committed atrocities against local nobles, but the nobles soon gave as good as they got, putting down the Jacquerie with exceptional brutality.

Similar revolts took place in England. The movement known as Wat Tyler’s Rebellion started in much of southern and central England when royal agents tried to collect poll taxes (a tax on each household) to finance the Hundred Years’ War. Refusing to pay and refusing to be arrested, the commons—peasants and small householders—rose up in rebellion in 1381. They massed in various groups, vowing “to slay all lawyers, and all jurors, and all the servants of the King whom they could find.” Marching to London to see the king, they began to make a more radical demand: an end to serfdom. Although the rebellion was put down and its leaders executed, peasants returned home to bargain with their lords for better terms. The death knell of serfdom in England had been sounded. (See “Document 13.1: Wat Tyler’s Rebellion.”)