The Ottoman Conquest of Constantinople, 1453

The Ottoman Conquest of Constantinople, 1453

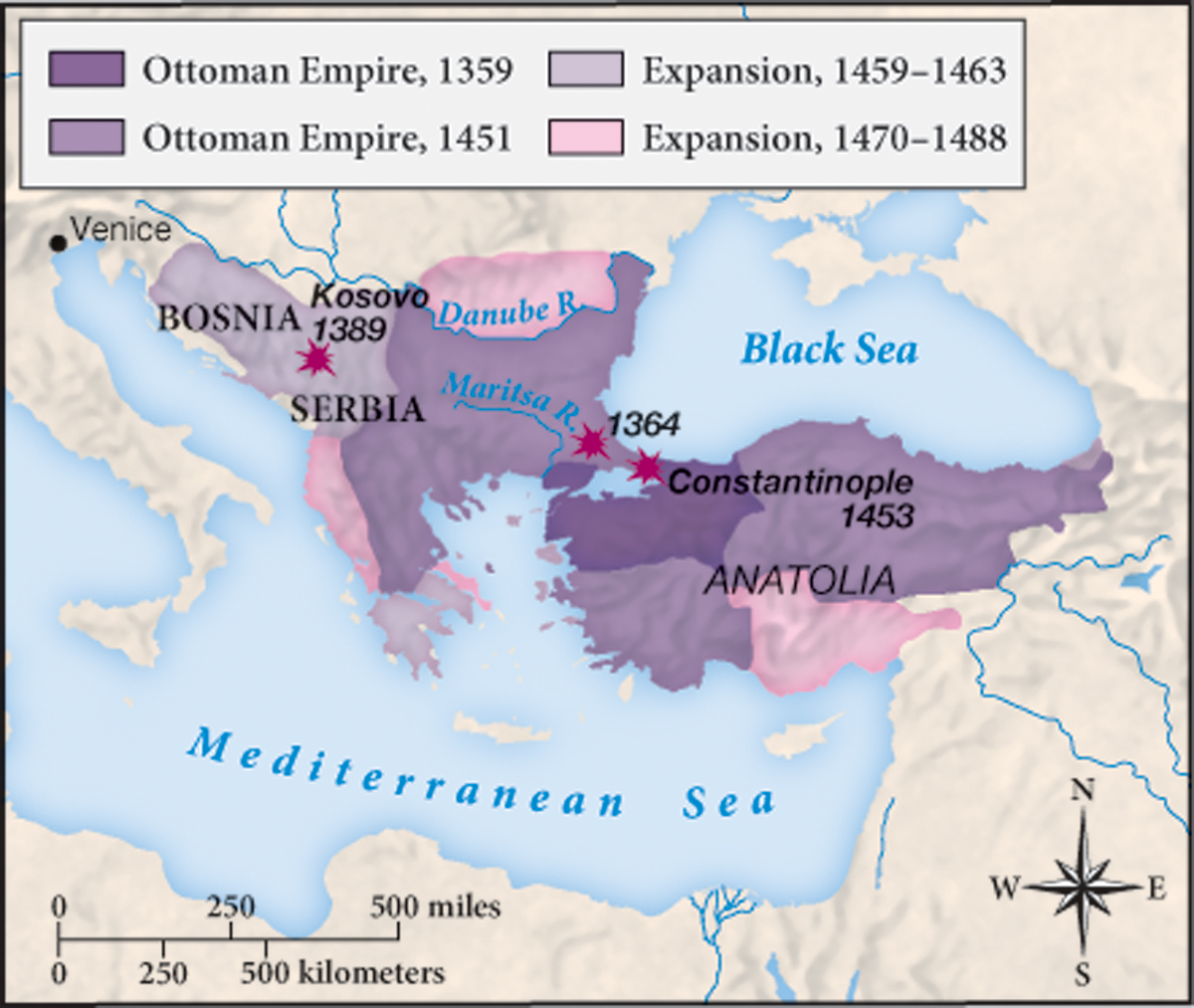

The end of the Hundred Years’ War coincided with an event that was even more decisive for all of Europe: the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans, who were converts to Islam, were one of several tribal confederations in central Asia. Starting as a small enclave between the Mongol Empire and Byzantium, and taking their name from a potent early leader, Osman I (r. 1280–1324), the Ottomans began to expand in the fourteenth century in a quest to wage holy war against infidels, or unbelievers.

During the next two centuries, the Ottomans took over the Balkans and Anatolia by both negotiations and arms (Map 13.3). They reduced the Byzantine Empire to the city of Constantinople and treated it as a vassal state. Under the sultan Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481), they besieged the city of Constantinople itself in 1453. Perhaps eighty thousand men confronted some three thousand defenders (the entire population of Constantinople was no more than fifty thousand) and a fleet from Genoa. The city held out until the end of May but was forced to capitulate when the sultan’s cannons breached the city’s land walls. Mehmed’s troops entered the city and plundered it thoroughly, killing the emperor and displaying his head in triumph.

The conquest of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire. But that was not the way Mehmed saw the matter. He conquered Constantinople in part to be a successor to the Roman emperors—a Muslim successor, to be sure. He turned Hagia Sophia (the great church built by the emperor Justinian in 538) into a mosque, as he did with most of the other Byzantine churches. He retained the city’s name, the City of Constantine—Qustantiniyya in Turkish—though it was popularly referred to as Istanbul, meaning, simply, “the city.”

Like the French and English kings after the Hundred Years’ War, the Ottoman sultans were centralizing monarchs who guaranteed law and order. The core of their army consisted of European Christian boys, who were requisitioned as tribute every five years. Trained in arms and converted to Islam, these young fighters made up the Janissaries—a highly disciplined military force also used to supervise local administrators throughout formerly Byzantine regions. Building a system of roads that crisscrossed their empire, the sultans made long-distance trade easy and profitable.

Once Constantinople was his, Mehmed embarked on an ambitious program of expansion and conquest. By 1500, the Ottoman Empire was a new and powerful state bridging Europe and the Middle East.