The Arts Confront Social Reality

The Arts Confront Social Reality

Culture helped the cause of national unity. A hungry reading public devoured biographies of political leaders, past and present, and credited daring heroes with creating the triumphant nation-state. As schooling spread literacy and a craving for realism—that is, true-to-life portrayals of society without romantic or idealistic overtones—commercially minded publishers produced an age of best sellers. Newspapers published the novels of Charles Dickens in serial form, and each installment attracted buyers eager for the latest plot twist. Drawn from English society, Dickens’s characters included starving orphans, grasping lawyers, greedy bankers, and ruthless opportunists. Hard Times (1854) depicts the grinding poverty and ill health of workers alongside the heartlessness of businessmen. Novelist George Eliot (the pen name of Mary Ann Evans) probed real-life dilemmas in The Mill on the Floss (1860) and Middlemarch (1871–1872). Describing rural society, Eliot allowed her readers to see one another’s predicaments, wherever they lived. She knew the pain of ordinary life from her own experience: despite her fame, she was a social outcast because she lived with a married man. Popular novels that showed a hard reality helped form a shared culture much as state institutions did.

French writers also scorned dreams of utopian, trouble-free societies and ideal beauty. Gustave Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary (1857) tells the story of a doctor’s wife who longs to escape her provincial surroundings. Filled with romantic fantasies, she has two love affairs to escape her boredom, becomes hopelessly indebted buying gifts for her lovers, and commits suicide by swallowing arsenic. Madame Bovary scandalized French society with its frank picture of women’s sexuality, but it attracted a wide readership. Poet Charles-Pierre Baudelaire wrote explicitly about sex; in his 1857 collection, Les Fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil), he expressed drug- and alcohol-induced passions—some focused on the brown body of his African mistress—and spun out visions that critics condemned as perverse. French authorities brought charges of obscenity against both Flaubert and Baudelaire. At issue was social and artistic order: “Art without rules is no longer art,” maintained the prosecutor.

During the era of Alexander II’s Great Reforms, Russian writers debated whether western European values were harming Russian culture. Adopting one viewpoint, Ivan Turgenev created a powerful novel of Russian life, Fathers and Sons (1862), a story of nihilistic children rejecting both parental authority and their parents’ spiritual values in favor of science and facts. Fyodor Dostoevsky, in contrast, portrayed nihilists as dark, ridiculous, and neurotic. The highly intelligent characters in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) are personally tormented and condemned to lead absurd, even criminal lives. Dostoevsky used antiheroes to emphasize spirituality and traditional Russian values but added a realistic spin by planting such values in ordinary, often seedy people. The Russian public was drawn together by these debates about Russian identity.

While writers of realism depended on sales to thousands of readers, painters usually depended on government support. Leaders such as Prince Albert of Great Britain actively patronized the arts and purchased works for official collections and for themselves. Having their artwork chosen for display at government-sponsored exhibitions was another way for artists to earn a living. Hundreds of thousands from all social classes attended these exhibitions, though not all could afford to buy the art.

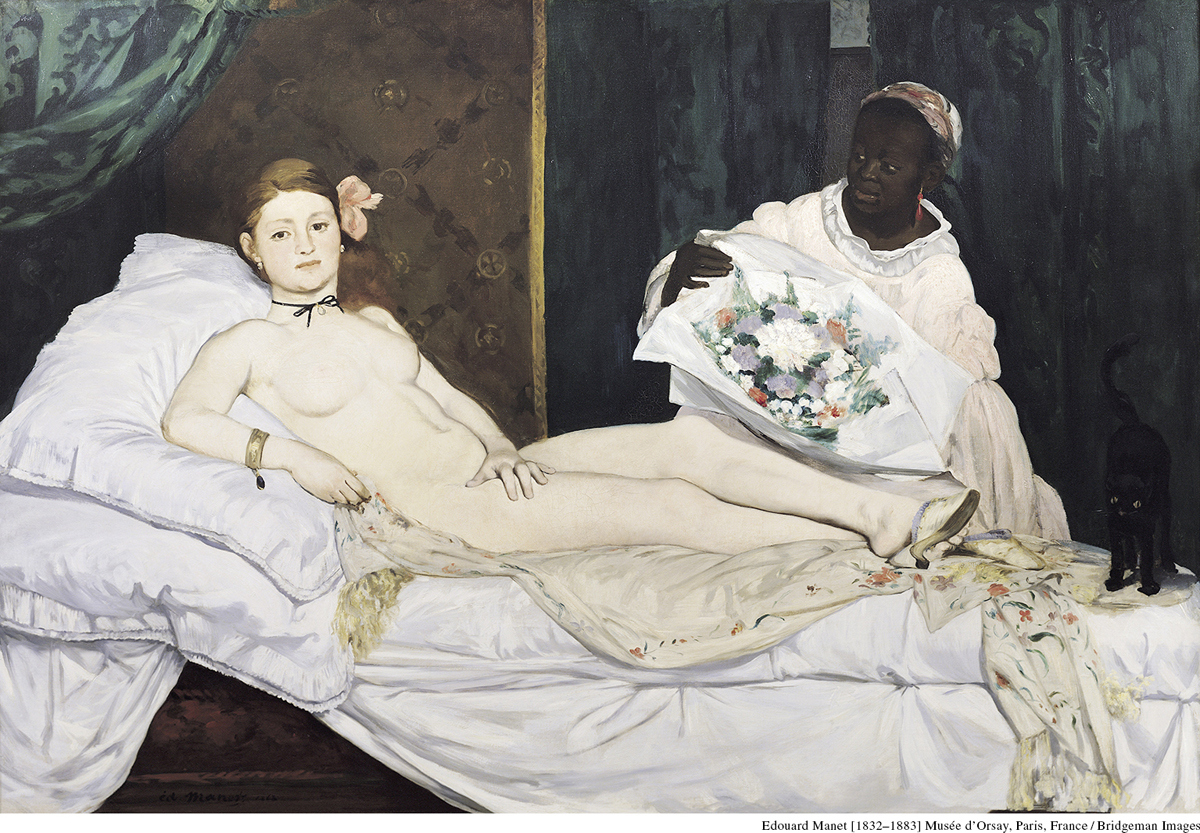

After the revolutions of 1848, artists began rejecting the romantic idealizing of ordinary folk or grand historic events. Instead, painters like Gustave Courbet portrayed groaning laborers at backbreaking work because, as he stated, an artist should “never permit sentiment to overthrow logic.” The renovated city, artists found, had become a visual spectacle; its wide new boulevards served as a stage on which urban residents performed. Universal Exhibition (1867) by Edouard Manet shows figures from all social classes gazing at the Paris scene and observing one another to learn correct modern behavior. Manet also broke with romantic conventions of the nude. His Olympia (1865) depicts a white courtesan lying on her bed, attended by a black woman (see the illustration). This disregard for depicting women in mythical or idealized settings was too much for the critics: “A sort of female gorilla,” one wrote of Olympia as debate raged over realism.

Unlike most of the visual arts, opera was commercially profitable and an effective means of reaching the nineteenth-century public. Verdi used musical theater to contrast noble ideals with the deadly effects of power and the lure of passion with the need for social order. The German composer Richard Wagner hoped to revolutionize opera by fusing music and drama to arouse the audience’s fear and awe. A gigantic cycle of four operas, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen reshaped ancient German myths into a modern, nightmarish story of a world doomed by its obsessive pursuit of money and power and saved only through unselfish love. His opera The Mastersingers of Nuremberg was said to be implicitly anti-Semitic because of its rejection of influences other than German ones in the arts. Wagner’s musical innovation made him a major force in philosophy, politics, and the arts across Europe. To his fellow citizens, however, his operas stood for Germany. Artists both implicitly (like George Eliot) and more explicitly (like Richard Wagner) promoted nation building even as they experimented with new forms.