Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 864

The Paris Peace Treaties

Seventy delegates from twenty-

This idealism was strengthened by President Wilson’s January 1918 peace proposal, the Fourteen Points. Wilson stressed national self-

The real powers at the conference were the United States, Great Britain, and France. Germany and Russia were excluded, and Italy’s role was limited. Almost immediately the three Allies began to quarrel. President Wilson insisted that the first order of business be the League of Nations. Wilson had his way, although Prime Ministers Lloyd George of Great Britain and, especially, Georges Clemenceau of France were unenthusiastic. They were primarily concerned with punishing Germany.

The “Big Three” were soon in a stalemate over Germany’s fate. Although personally inclined to make a somewhat moderate peace with Germany, Lloyd George felt pressured for a victory worthy of the sacrifices of total war. Clemenceau also wanted revenge and lasting security for France, which, he believed, required the creation of a buffer state between France and Germany, Germany’s permanent demilitarization, and vast German reparations. Wilson, supported by Lloyd George, would hear none of this.

In the end, Clemenceau agreed to a compromise. He gave up the French demand for a Rhineland buffer state in return for a formal defensive alliance with the United States and Great Britain. Both Wilson and Lloyd George also promised their countries would come to France’s aid if it was attacked.

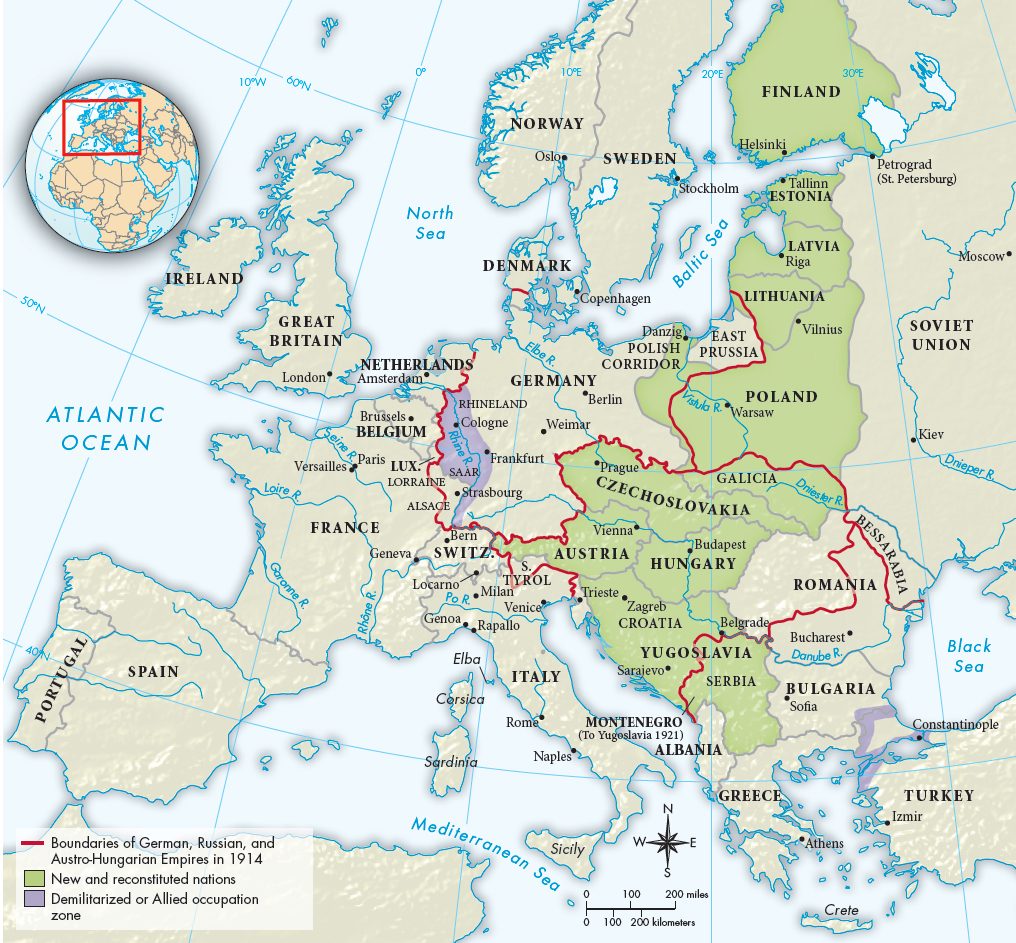

The Treaty of Versailles was the first step toward re-

ANALYZING THE MAP: What territory did Germany lose, and to whom? What new independent states were formed from the old Russian empire?CONNECTIONS: How were the principles of national self-

More harshly, the Allies declared that Germany (with Austria) was responsible for the war and therefore had to pay reparations equal to all civilian damages caused by the war. The actual reparations figure was not set, however, leaving open the possibility that it might be set at a reasonable level in the future when tempers had cooled.

Other agreements reached in Paris also had far-

Promises of independence made to Arab leaders were largely brushed aside, and Britain and France extended their power in the Middle East, taking advantage of the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. As League of Nations mandates, the French received Lebanon and Syria, and Britain took Iraq and Palestine. Palestine was to include a Jewish national homeland first promised by Britain in 1917 in the Balfour Declaration (see “The Arab Revolt” in Chapter 29). These Allied acquisitions, although officially League of Nations mandates, were one of the most imperialistic elements of the peace settlement. Another was mandating Germany’s holdings in China to Japan (see “The Rise of Nationalist China” in Chapter 29). Germany’s African colonies were mandated to Great Britain, France, South Africa, and Belgium. The mandates system left colonial peoples in the Middle East, Asia (see Chapter 29), and Africa bitterly disappointed and demonstrated that the age of Western and Eastern imperialism lived on.