7.1 The Economics of Taxes: A Preliminary View

An excise tax is a per unit tax on sales of a good or service.

To understand the economics of taxes, it’s helpful to look at a simple type of tax known as an excise tax—a tax charged on each unit of a good or service that is sold. Most tax revenue in Canada comes from other kinds of taxes, which we’ll describe later in this chapter. But excise taxes are common. For example, there are excise taxes on gasoline, cigarettes, and fuel-

The Effect of an Excise Tax on Quantities and Prices

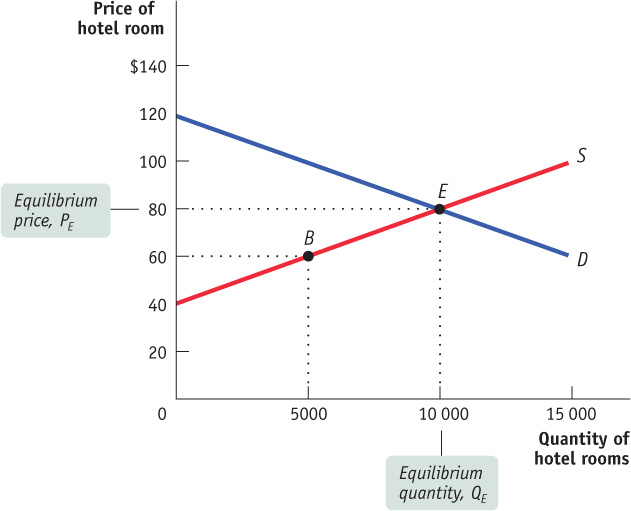

Suppose that the supply and demand for hotel rooms in the city of Potterville are as shown in Figure 7-1. We’ll make the simplifying assumption that all hotel rooms are the same. In the absence of taxes, the equilibrium price of a room is $80 per night and the equilibrium quantity of hotel rooms rented is 10 000 per night.

Now suppose that Potterville’s government imposes an excise tax of $40 per night on hotel rooms—

What does this imply about the supply curve for hotel rooms in Potterville? To answer this question, we must compare the incentives of hotel owners pre-

From Figure 7-1 we know that pre-

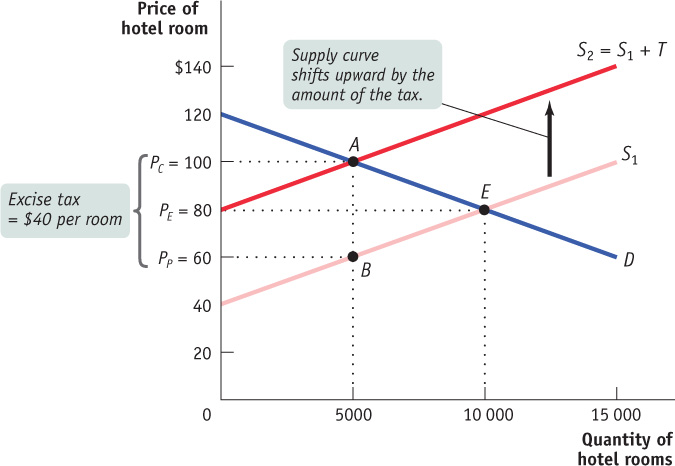

The upward shift of the supply curve caused by the tax is shown in Figure 7-2, where T is the amount of tax, S1 is the pre-

Let’s check this again. How do we know that 5000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $100? Because the price net of tax (PP = PC − T) is $60, and according to the original supply curve, 5000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $60, as shown by point B in Figure 7-2.

Does this look familiar? It should. In Chapter 5 we described the effects of a quota on sales: a quota drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. An excise tax does the same thing. As a result of this wedge, consumers pay more (PC) and producers receive less (PP), with the gap being the tax wedge (T), so that PC = PP + T.

In our example, consumers—

It’s important to recognize that as we’ve described it, Potterville’s hotel tax is a tax on the hotel owners, not their guests—

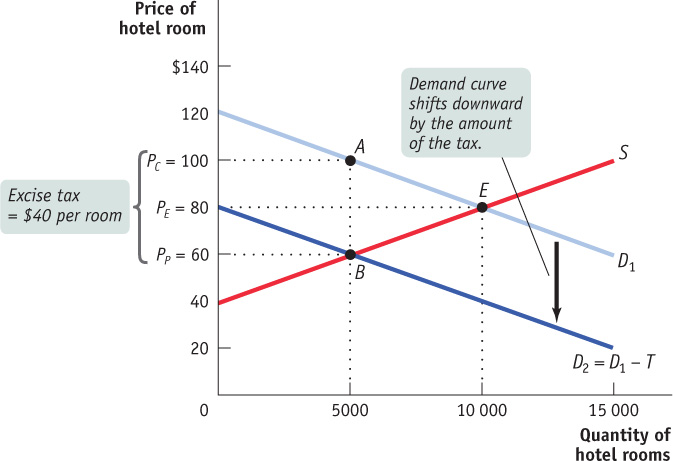

What would happen if the city levied a tax on consumers instead of producers? That is, suppose that instead of requiring hotel owners to pay $40 a night for each room they rent, the city required hotel guests to pay $40 for each night they stayed in a hotel. The answer is shown in Figure 7-3. If a hotel guest must pay a tax of $40 per night, then the pre-

At every quantity demanded, the demand price—

If you compare Figures 7-2 and 7-3, you will immediately notice that they show the same price effect. In each case, consumers pay an effective price of $100 (PC), producers receive an effective price of $60 (PP), and 5000 hotel rooms are bought and sold. In fact, it doesn’t matter who the government officially asks to pay the tax—

The incidence of a tax is a measure of who really pays it.

This insight illustrates a general principle of the economics of taxation: the incidence of a tax—

Price Elasticities and Tax Incidence

We’ve just learned that the economic incidence of an excise tax doesn’t depend on whom the government rules require to officially pay it. In the example shown in Figures 7-1 through 7-3, a tax on hotel rooms falls equally on consumers and producers, no matter who the tax is levied on. But it’s important to note that this 50–50 split between consumers and producers is a result of our assumptions in this example. In the real world, the incidence of an excise tax usually falls unevenly between consumers and producers, as one group bears more of the burden than the other.

What determines how the burden of an excise tax is allocated between consumers and producers? The answer depends on the shapes of the supply and the demand curves. More specifically, the incidence of an excise tax depends on the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of demand. We can see this by looking first at a case in which consumers pay most of an excise tax, then at a case in which producers pay most of the tax.

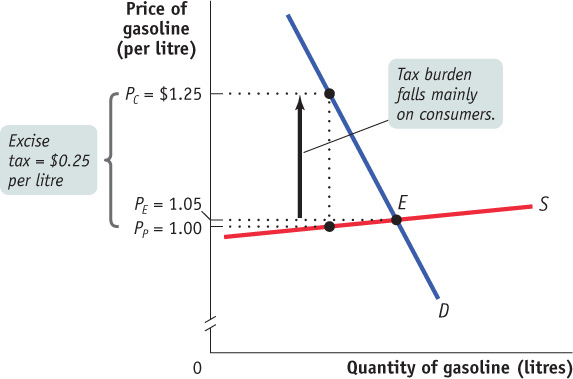

When an Excise Tax Is Paid Mainly by Consumers Figure 7-4 shows an excise tax that falls mainly on consumers: an excise tax on gasoline, which we set at $0.25 per litre. (There really is a federal excise tax on gasoline, though it is actually only $0.10 per litre in Canada. In addition, provinces, territories, and even several cities impose excise taxes between $0.09 and $0.24 per litre. Finally, the GST/HST and, if applicable, provincial sales taxes also apply to gasoline sales.) According to Figure 7-4, in the absence of the tax, gasoline would sell for $1.05 per litre.

Two key assumptions are reflected in the shapes of the supply and demand curves in Figure 7-4. First, the price elasticity of demand for gasoline is assumed to be very low, so the demand curve is relatively steep. Recall that a low price elasticity of demand means that the quantity demanded changes little in response to a change in price—a feature of a steep demand curve. Second, the price elasticity of supply of gasoline is assumed to be very high, so the supply curve is relatively flat. A high price elasticity of supply means that the quantity supplied changes a lot in response to a change in price—a feature of a relatively flat supply curve.

We have just learned that an excise tax drives a wedge, equal to the size of the tax, between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. This wedge drives the price paid by consumers up and the price received by producers down. But as we can see from Figure 7-4, in this case those two effects are very unequal in size. The price received by producers falls only slightly, from $1.05 to $1.00, but the price paid by consumers rises by a lot, from $1.05 to $1.25. In this case consumers bear the greater share of the tax burden.

This example illustrates another general principle of taxation: When the price elasticity of demand is low and the price elasticity of supply is high, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. Why? A low price elasticity of demand means that consumers have few substitutes and so little alternative to buying higher-priced gasoline. In contrast, a high price elasticity of supply results from the fact that producers have many production substitutes for their gasoline (that is, other uses for the crude oil from which gasoline is refined). This gives producers much greater flexibility in refusing to accept lower prices for their gasoline. And, not surprisingly, the party with the least flexibility—in this case, consumers—gets stuck paying most of the tax. This is a good description of how the burden of the main excise taxes actually collected in Canada today, such as those on cigarettes and alcoholic beverages, is allocated between consumers and producers.

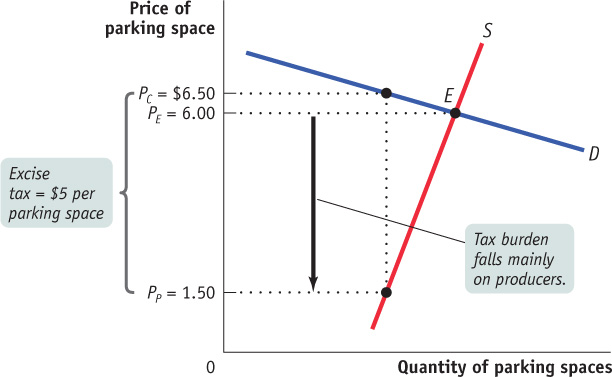

When an Excise Tax Is Paid Mainly by Producers Figure 7-5 shows an example of an excise tax paid mainly by producers, a $5.00 per day tax on downtown parking in a small city. In the absence of the tax, the market equilibrium price of parking is $6.00 per day.

We’ve assumed in this case that the price elasticity of supply is very low because the lots used for parking have very few alternative uses. This makes the supply curve for parking spaces relatively steep. The price elasticity of demand, however, is assumed to be high: consumers can easily switch from the downtown spaces to other parking spaces a few minutes’ walk from downtown, spaces that are not subject to the tax. This makes the demand curve relatively flat.

The tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. In this example, however, the tax causes the price paid by consumers to rise only slightly, from $6.00 to $6.50, but the price received by producers falls a lot, from $6.00 to $1.50. In the end, consumers bear only $0.50 of the $5.00 tax burden, with producers bearing the remaining $4.50.

Again, this example illustrates a general principle: When the price elasticity of demand is high and the price elasticity of supply is low, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on producers. A real-world example is a tax on purchases of existing houses. Just before the recession hit Canada in 2008, the cash-strapped city of Toronto implemented a municipal land transfer tax to raise revenue. A land transfer tax is collected as a percentage of the price at which a residential or commercial property sells. To politicians, the idea was simple: homes sales were strong and in the preceding years prices had steadily risen. The tax rate was designed to rise somewhat as the price increased, so to some degree the higher the price paid the more tax paid in both relative and absolute terms. So besides helping the city meet its budgetary needs, the tax was intended to be paid mostly by well-off outsiders moving into desirable locations and purchasing homes from the less well-off original occupants. But this ignores the fact that the price elasticity of demand for houses in Toronto is often high, because potential buyers can choose to move to other towns. Furthermore, the price elasticity of supply is often low because most sellers must sell their houses due to job transfers or to provide funds for their retirement. So taxes on home purchases are actually paid mainly by the less well-off sellers—not, as Toronto officials may have imagined, by wealthy buyers.2

Putting It All Together We’ve just seen that when the price elasticity of supply is high and the price elasticity of demand is low, an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. And when the price elasticity of supply is low and the price elasticity of demand is high, an excise tax falls mainly on producers. This leads us to the general rule: When the price elasticity of demand is higher than the price elasticity of supply, an excise tax falls mainly on producers. When the price elasticity of supply is higher than the price elasticity of demand, an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. So it is elasticity—not the tax legislation—that determines the incidence of an excise tax.

WHO PAYS CANADA’S PAYROLL TAXES?

Anyone who works for an employer receives a paycheque that itemizes not only the wages paid but also the money deducted from the paycheque for various taxes. For most people, one of the big deductions is for Canada’s various payroll taxes. Nationally these payroll taxes fund the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), a national pension plan for Canada’s workers (workers in Quebec contribute to the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP)), and Employment Insurance (EI), an insurance program that provides assistance to many of Canada’s workers during spells of unemployment. At the provincial level, payroll taxes exist to fund worker compensation systems for injured workers and, in some cases, to help fund provincial health and education spending.

In 2013, most Canadian workers paid 6.83% of about the first $50 000 of their earnings in CPP (4.95%) and EI (1.88%) contributions. But this isn’t even the half of it: each employer is required to pay an amount equal to the CPP contributions and 1.4 times the EI contributions of its employees. And when it comes to the various other provincial payroll taxes, which range from 1.12% to as much as 6.34%, the employer is expected to pay the entire amount.

How should we think about Canada’s payroll taxes? Are they really shared by workers and employers? We can use our previous analysis to answer that question because payroll taxes are like an excise tax—a tax on the sale and purchase of labour. A portion of it is a tax levied on the sellers—that is, workers. The rest is a tax levied on the buyers—that is, employers.

But we already know that the incidence of a tax does not really depend on who actually makes out the cheque. Almost all economists agree that payroll taxes are more costly for workers than for their employers. The reason for this conclusion lies in a comparison of the price elasticities of the supply of labour by households and the demand for labour by firms. Evidence indicates that the price elasticity of demand for labour is quite high, at least 3. That is, an increase in average wages of 1% would lead to at least a 3% decline in the number of hours of work demanded by employers. Labour economists believe, however, that the price elasticity of supply of labour is very low. The reason is that although a fall in the wage rate reduces the incentive to work more hours, it also makes people poorer and less able to afford leisure time. The strength of this second effect is shown in the data: the number of hours people are willing to work falls very little—if at all—when the wage per hour goes down.

Our general rule of tax incidence says that when the price elasticity of demand is much higher than the price elasticity of supply, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on the suppliers. So the burden of Canada’s payroll taxes falls mainly on the suppliers of labour, that is, workers—even though on paper most of these taxes are paid by employers. Payroll taxes are largely borne by workers in the form of lower wages, rather than by employers in the form of lower profits.

This conclusion tells us something important about the Canadian tax system: payroll taxes, rather than the much-maligned income tax, are the main tax burden on families in the lower half of the income distribution. For most workers, payroll taxes amount to more than 15.5% of all wages and salaries up to about $50 000 per year (note that 6.83% + 4.95% + 1.4 × 1.88% + 1.12% = 15.532%). Thus, the great majority of workers in Canada pay at least 15.5% of their wages in payroll taxes. Meanwhile, only middle- and high-income Canadian families pay more than 15% of their income in income tax. In fact, according to the Fraser Institute, the average Canadian household earned an income of $74 113 in 2012 and paid $9195 in income taxes and $6769 in payroll taxes, which represented 29.1% and 21.4% of the total taxes paid by such a family. So for the average family, payroll taxes represent their second largest tax burden.

Quick Review

An excise tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and that received by producers, leading to a fall in the quantity transacted. It creates inefficiency by distorting incentives and creating missed opportunities.

The incidence of an excise tax doesn’t depend on whom the tax is officially levied on. Rather, it depends on the price elasticities of demand and of supply.

The higher the price elasticity of supply and the lower the price elasticity of demand, the heavier the burden of an excise tax on consumers. The lower the price elasticity of supply and the higher the price elasticity of demand, the heavier the burden on producers.

Check Your Understanding 7-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 7-1

Question 7.1

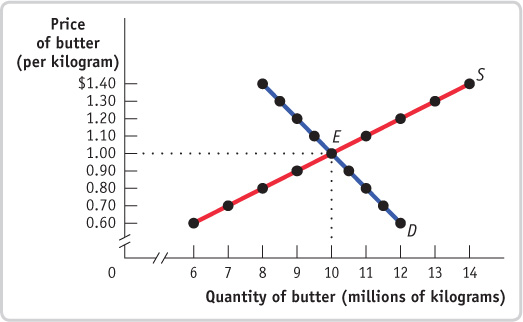

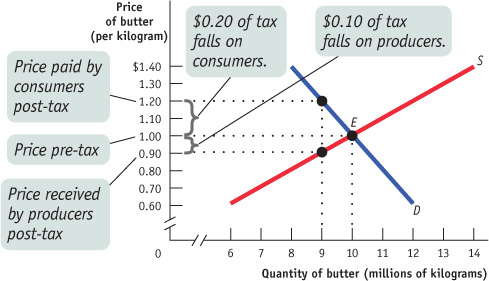

Consider the market for butter, shown in the accompanying figure. The government imposes an excise tax of $0.30 per kilogram of butter. What is the price paid by consumers post-tax? What is the price received by producers post-tax? What is the quantity of butter transacted? How is the incidence of the tax allocated between consumers and producers? Show this on the figure.

The following figure shows that, after introduction of the excise tax, the price paid by consumers rises to $1.20; the price received by producers falls to $0.90. Consumers bear $0.20 of the $0.30 tax per kilogram of butter; producers bear $0.10 of the $0.30 tax per kilogram of butter. The tax drives a wedge of $0.30 between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. As a result, the quantity of butter bought and sold is now 9 million kilograms.

Question 7.2

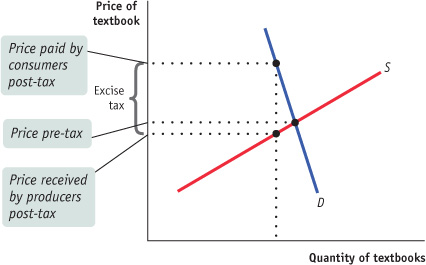

The demand for economics textbooks is very inelastic, but the supply is somewhat elastic. What does this imply about the incidence of an excise tax? Illustrate with a diagram.

The fact that demand is very inelastic means that consumers will reduce their demand for textbooks very little in response to an increase in the price caused by the tax. The fact that supply is somewhat elastic means that suppliers will respond to the fall in the price by reducing supply. As a result, the incidence of the tax will fall heavily on consumers of economics textbooks and very little on publishers, as shown in the accompanying figure.

Question 7.3

True or false? When a substitute for a good is readily available to consumers, but it is difficult for producers to adjust the quantity of the good produced, then the burden of a tax on the good falls more heavily on producers.

True. When a substitute is readily available, demand is elastic. This implies that producers cannot easily pass on the cost of the tax to consumers because consumers will respond to an increased price by switching to the substitute. Furthermore, when producers have difficulty adjusting the amount of the good produced, supply is inelastic. That is, producers cannot easily reduce output in response to a lower price net of tax. So the tax burden will fall more heavily on producers than consumers.

Question 7.4

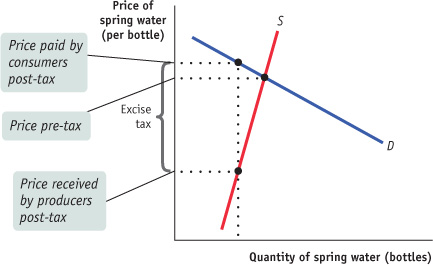

The supply of bottled spring water is very inelastic, but the demand for it is somewhat elastic. What does this imply about the incidence of a tax? Illustrate with a diagram.

The fact that supply is very inelastic means that producers will reduce their supply of bottled water very little in response to the fall in price caused by the tax. Demand, on the other hand, will fall in response to an increase in price because demand is somewhat elastic. As a result, the incidence of the tax will fall heavily on producers of bottled spring water and very little on consumers, as shown in the accompanying figure.

Question 7.5

True or false? Other things equal, consumers would prefer to face a less elastic supply curve for a good or service when an excise tax is imposed.

True. The lower the elasticity of supply, the more the burden of a tax will fall on producers rather than consumers, other things equal.