Writing Definitions

The world of business and industry depends on clear definitions. Suppose you learn at a job interview that the prospective employer pays tuition and expenses for employees’ job-related education. You would need to study the employee-benefits manual to understand just what the company would pay for. Who, for instance, is an employee? Is it anyone who works for the company, or is it someone who has worked for the company full-time (40 hours per week) for at least six uninterrupted months? What is tuition? Does it include incidental laboratory or student fees? What is job-related education? Does a course about time management qualify? What, in fact, constitutes education?

Definitions are common in communicating policies and standards “for the record.” Definitions also have many uses outside legal or contractual contexts. Two such uses occur frequently:

Definitions clarify a description of a new development or a new technology in a technical field. For instance, a zoologist who has discovered a new animal species names and defines it.

Definitions help specialists communicate with less-knowledgeable readers. A manual explaining how to tune up a car includes definitions of parts and tools.

Definitions, then, are crucial in many kinds of technical communication. All readers, from the general reader to the expert, need effective definitions to carry out their jobs.

ANALYZING THE WRITING SITUATION FOR DEFINITIONS

For more about audience and purpose, see Ch. 4.

The first step in writing effective definitions is to analyze the writing situation: the audience and the purpose of the document. Physicists wouldn’t need a definition of entropy, but lawyers might. Builders know what a molly bolt is, but many insurance agents don’t. When you write for people whose first language is not English, consider adding a glossary (a list of definitions), using Simplified English and easily recognizable terms in your definitions, and using graphics to help readers understand a term or concept.

Think, too, about your purpose. For readers who need only a basic understanding of a concept—say, time-sharing vacation resorts—a brief, informal definition is usually sufficient. However, readers who need to understand an object, process, or concept thoroughly and be able to carry out related tasks need a more formal and detailed definition. For example, the definition of a “Class 2 Alert” written for operators at a nuclear power plant must be comprehensive, specific, and precise.

The appropriate type of definition depends on your audience and purpose. You have three major choices: parenthetical, sentence, and extended.

WRITING SENTENCE DEFINITIONS

The following Guidelines box presents more advice on sentence definitions.

Writing Effective Sentence Definitions

The following five suggestions can help you write effective sentence definitions.

Be specific in stating the category and the distinguishing characteristics. If you write, “A Bunsen burner is a burner that consists of a vertical metal tube connected to a gas source,” the imprecise category—“a burner”—ruins the definition: many types of large-scale burners use vertical metal tubes connected to gas sources.

Don’t describe a specific item if you are defining a general class of items. If you wish to define catamaran, don’t describe a particular catamaran. The one you see on the beach in front of you might be made by Hobie and have a white hull and blue sails, but those characteristics are not essential to all catamarans.

Avoid writing circular definitions—that is, definitions that merely repeat the key words or the distinguishing characteristics of the item being defined in the category. The definition “A required course is a course that is required” is useless: required of whom, by whom? However, in defining electron microscopes, you can repeat microscope because microscope is not the difficult part of the term. The purpose of defining electron microscope is to clarify electron as it applies to a particular type of microscope.

Be sure the category contains a noun or a noun phrase rather than a phrase beginning with when, what, or where.

INCORRECT A brazier is what is used to . . . CORRECT A brazier is a metal pan used to . . . INCORRECT Hypnoanalysis is when hypnosis is used to . . . CORRECT Hypnoanalysis is a psychoanalytical technique in which . . . Consider including a graphic. A definition of an electron microscope would probably include a photograph, diagram, or drawing, for example.

WRITING EXTENDED DEFINITIONS

An extended definition is a more-detailed explanation—usually one or more paragraphs—of an object, process, or idea. Often an extended definition begins with a sentence definition, which is then elaborated. For instance, the sentence definition “An electrophorus is a laboratory instrument used to generate static electricity” tells you the basic function of the device, but it doesn’t explain how it works, what it is used for, or its strengths and limitations. An extended definition would address these and other topics.

There is no one way to “extend” a definition. Your analysis of your audience and the purpose of your communication will help you decide which method to use. In fact, an extended definition sometimes employs several of the eight techniques discussed here.

Graphics Perhaps the most common way to present an extended definition in technical communication is to include a graphic and then explain it. Graphics are useful in defining not only physical objects but also concepts and ideas. A definition of temperature inversion, for instance, might include a diagram showing the forces that create temperature inversions.

The following passage from an extended definition of additive color shows how graphics can complement words in an extended definition.

The graphic effectively and economically clarifies the concept of additive color.

Additive color is the type of color that results from mixing colored light, as opposed to mixing pigments such as dyes or paints. When any two colored lights are mixed, they produce a third color that is lighter than either of the two original colors, as shown in this diagram. And when green, red, and blue lights are mixed together in equal parts, they form white light.

We are all familiar with the concept of additive color from watching TV monitors. A TV monitor projects three beams of electrons—one each for red, blue, and green—onto a fluorescent screen. Depending on the combinations of the three colors, we see different colors on the screen.

Examples Examples are particularly useful in making an abstract term easier to understand. The following paragraph is an extended definition of hazing activities (Fraternity Insurance and Purchasing Group, 2013).

This extended definition is effective because the writer has presented a clear sentence definition followed by numerous examples.

No chapter, colony, student or alumnus shall conduct or condone hazing activities. Hazing activities are defined as: “Any action taken or situation created, intentionally, whether on or off fraternity premises, to produce mental or physical discomfort, embarrassment, harassment, or ridicule. Such activities may include but are not limited to the following: use of alcohol; paddling in any form; creation of excessive fatigue; physical and psychological shocks; quests, treasure hunts, scavenger hunts, road trips or any other such activities carried on outside or inside of the confines of the chapter house; wearing of public apparel which is conspicuous and not normally in good taste; engaging in public stunts and buffoonery; morally degrading or humiliating games and activities; and any other activities which are not consistent with academic achievement, fraternal law, ritual or policy or the regulations and policies of the educational institution or applicable state law.”

Partition Partitioning is the process of dividing a thing or an idea into smaller parts so that readers can understand it more easily. The following example (Brain, 2005) uses partition to define computer infection.

Types of Infection

When you listen to the news, you hear about many different forms of electronic infection. The most common are:

Viruses—A virus is a small piece of software that piggybacks on real programs. For example, a virus might attach itself to a program such as a spreadsheet program. Each time the spreadsheet program runs, the virus runs, too, and it has the chance to reproduce (by attaching to other programs) or wreak havoc.

Email viruses—An email virus moves around in email messages, and usually replicates itself by automatically mailing itself to dozens of people in the victim’s email address book.

Worms—A worm is a small piece of software that uses computer networks and security holes to replicate itself. A copy of the worm scans the network for another machine that has a specific security hole. It copies itself to the new machine using the security hole, and then starts replicating from there, as well.

Trojan horses—A Trojan horse is simply a computer program. The program claims to do one thing (it may claim to be a game) but instead does damage when you run it (it may erase your hard disk). Trojan horses have no way to replicate automatically.

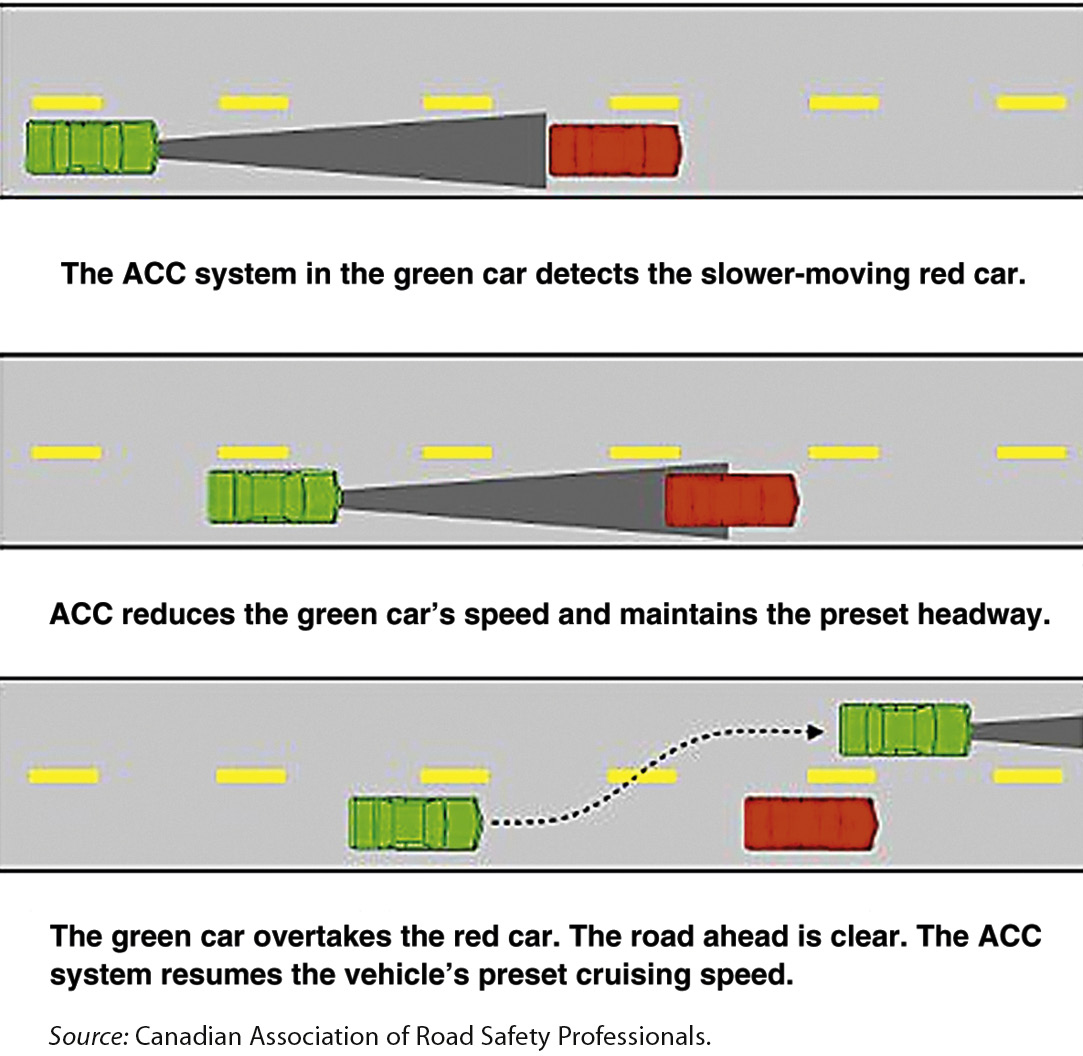

Principle of Operation Describing the principle of operation—the way something works—is an effective way to develop an extended definition, especially for an object or a process. The following excerpt from an extended definition of adaptive cruise control is based on the mechanism’s principle of operation.

Adaptive cruise control (ACC) employs sensing and control systems to monitor the vehicle’s position with respect to any vehicle ahead. When a vehicle equipped with ACC approaches a slower-moving vehicle, the ACC system reduces the vehicle speed in order to maintain a preset following distance (headway). However, when the traffic ahead clears, the ACC system automatically accelerates the vehicle back to the preset travel speed.

ACC systems use forward-looking radar or laser detection (lidar) systems to monitor the vehicle’s position with respect to any vehicle in front and change the speed in order to maintain a preset following distance (headway).

The system typically allows the driver to preset a “following time,” for example a two-second gap between vehicles. The ACC computer makes calculations of speed, distance and time based on the sensor inputs and makes appropriate adjustments to the vehicle’s speed to maintain the desired headway.

Comparison and Contrast Using comparison and contrast, a writer discusses the similarities or differences between the item being defined and an item with which readers are more familiar. The following definition of VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) contrasts this new form of phone service to the form we all know.

Voice over Internet Protocol is a form of phone service that lets you connect to the Internet through your cable or DSL modem. VoIP service uses a device called a telephony adapter, which attaches to the broadband modem, transforming phone pulses into IP packets sent over the Internet.

In this excerpt, the second and third paragraphs briefly compare VoIP and traditional phone service.

VoIP is considerably cheaper than traditional phone service: for as little as $20 per month, users get unlimited local and domestic long-distance service. For international calls, VoIP service is only about three cents per minute, about a third the rate of traditional phone service. In addition, any calls from one person to another person with the same VoIP service provider are free.

However, sound quality on VoIP cannot match that of a traditional land-based phone. On a good day, the sound is fine on VoIP, but frequent users comment on clipping and dropouts that can last up to a second. In addition, sometimes the sound has the distant, tinny quality of some of today’s cell phones.

Analogy An analogy is a specialized kind of comparison. In a traditional comparison, the writer compares one item to another, similar item: an electron microscope to a light microscope, for example. In an analogy, however, the item being defined is compared to an item that is in some ways completely different but that shares some essential characteristic. For instance, the central processing unit of a computer is often compared to a brain. Obviously, these two items are very different, except that the relationship of the central processing unit to the computer is similar to that of the brain to the body.

The following example from a definition of decellularization (Falco, 2008) shows an effective use of an analogy.

The writer of this passage uses the analogy of gutting a house to clarify the meaning of decellularization.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota were able to create a beating [rat] heart using the outer structure of one heart and injecting heart cells from another rat. Their findings are reported in the journal Nature Medicine. Rather than building a heart from scratch, which has often been mentioned as a possible use for stem cells, this procedure takes a heart and breaks it down to the outermost shell. It’s similar to taking a house and gutting it, then rebuilding everything inside. In the human version, the patient’s own cells would be used.

Negation A special kind of contrast is negation, sometimes called negative statement. Negation clarifies a term by distinguishing it from a different term with which readers might confuse it. The following example uses negation to distinguish the term ambulatory from ambulance.

An ambulatory patient is not a patient who must be moved by ambulance. On the contrary, an ambulatory patient is one who can walk without assistance from another person.

Negation is rarely the only technique used in an extended definition; in fact, it is used most often in a sentence or two at the start. Once you have explained what something is not, you still have to explain what it is.

Etymology Citing a word’s etymology, or derivation, is often a useful and interesting way to develop a definition. The following example uses the etymology of spam—unsolicited junk email—to define it.

For many decades, Hormel Foods has manufactured a luncheon meat called Spam, which stands for “Shoulder Pork and hAM”/“SPiced hAM.” Then, in the 1970s, the English comedy team Monty Python’s Flying Circus broadcast a skit about a restaurant that served Spam with every dish. In describing each dish, the waitress repeats the word Spam over and over, and several Vikings standing in the corner chant the word repeatedly. In the mid-1990s, two businessmen hired a programmer to write a program that would send unsolicited ads to thousands of electronic newsgroups. Just as Monty Python’s chanting Vikings drowned out other conversation in the restaurant, the ads began drowning out regular communication online. As a result, people started calling unsolicited junk email spam.

Etymology is a popular way to begin definitions of acronyms, which are abbreviations pronounced as words:

RAID, which stands for redundant array of independent (or inexpensive) disks, refers to a computer storage system that can withstand a single (or, in some cases, even double) disk failure.

Etymology, like negation, is rarely used alone in technical communication, but it provides an effective way to introduce an extended definition.

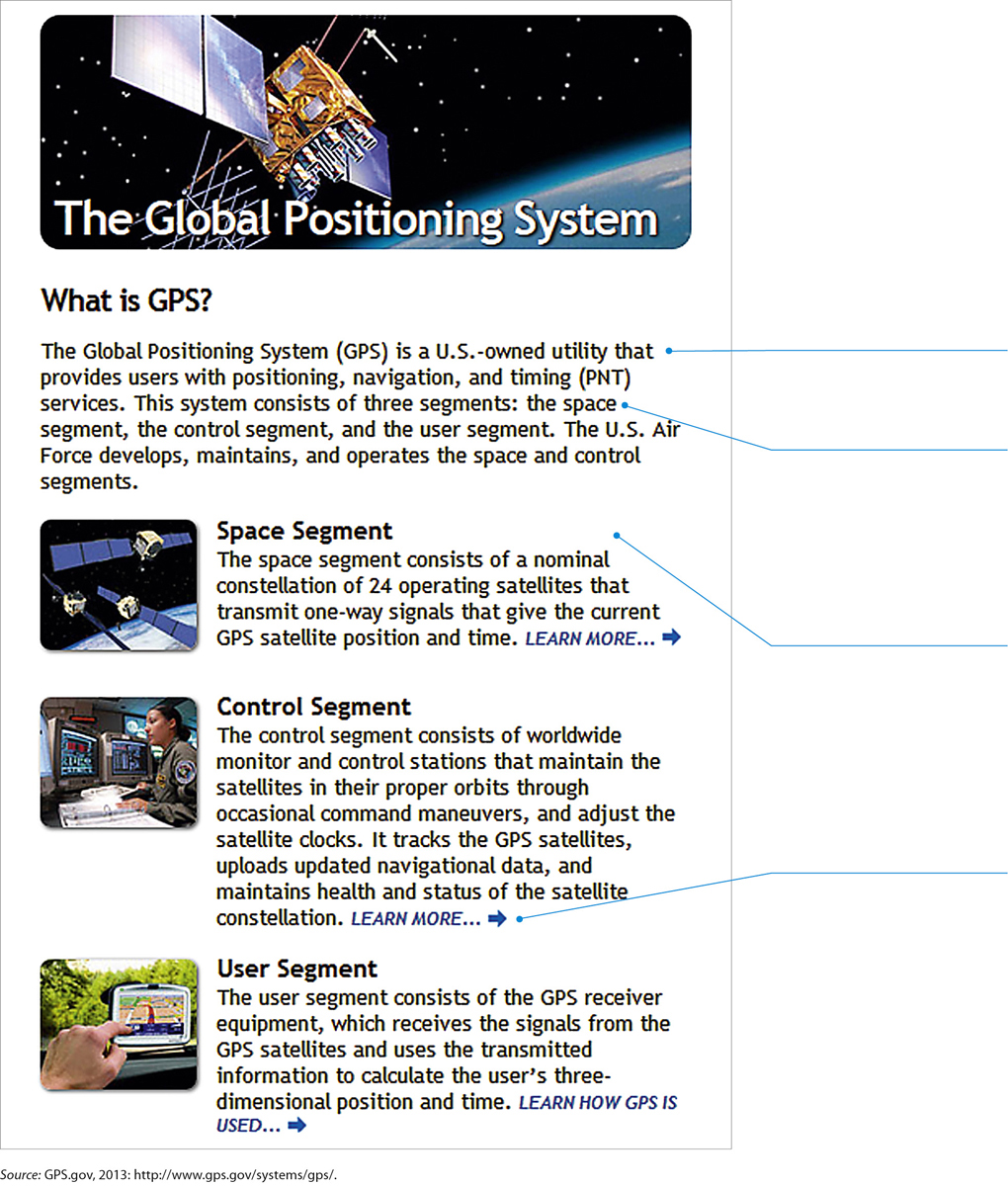

A Sample Extended Definition Figure 14.1 is an example of an extended definition addressed to a general audience.

The first paragraph of this extended definition of GPS begins with a sentence definition.

The second sentence serves as an advance organizer for the definition, explaining that the definition will be extended by partition: GPS consists of three segments.

The body of this extended definition consists of three sections, each of which is introduced by a graphic and a topic sentence explaining the segment.

Links lead the reader to much more information about each segment, including more text, diagrams, and videos.