Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Supporting a Position with Sources

Identify a cluster of readings about a topic that interests you. For example, choose related readings from this book or from other readings assigned in your class. If your topic is assigned and you don’t begin with much interest in it, develop your intellectual curiosity. Look for an angle, an implication, or a vantage point that will engage you. Relate the topic in some way to your experience. Read (or reread) the selections, considering how each supports, challenges, or deepens your understanding of the topic.

Based on the information in your cluster of readings, develop an enlightening position about the topic that you’d like to share with an audience of college readers. Support this position—your working thesis—using quotations, paraphrases, summaries, and syntheses of the information in the readings as evidence. Present your information from sources clearly, and credit your sources appropriately.

Three students investigated topics of great variety:

One student examined local language usage that combined words from English and Spanish, drawing on essays about language diversity to analyze the patterns and implications of such usage.

Another writer used a cluster of readings about technology to evaluate the privacy issues on a popular social media site.

A third, using personal experience with a blended family and several essays on families, challenged misconceptions about today’s families.

Facing the Challenge Finding Your Voice

For more on evidence, see Ch. 9.

The major challenge that writers face when using sources to support a position is finding their own voice. You create your voice as a college writer through your choice of language and angle of vision. You probably want to present yourself as a thoughtful writer with credible insights, someone a reader will want to hear from.

Finding your own voice may be difficult in a source-based paper. By the time you have supported your position by quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing relevant readings, you may worry that your sources have taken over your paper. You may feel there’s no room left for your own voice and, even if there were, it’s too quiet to jostle past the powerful words of your sources. That, however, is your challenge.

As you develop your voice as a college writer and use it to guide your readers’ understanding, you’ll restrict sources to their proper role as supporting evidence. Don’t let them get pushy or dominate your writing. Use these questions to help you strengthen your voice:

Can you write a list or passage explaining what you’d like readers to hear from your voice? Where could you add more of this in your draft?

Have you used your own voice, not quotations or paraphrases from sources, to introduce your topic, state your thesis, and draw conclusions?

Have you generally relied on your own voice to open and conclude paragraphs and to reinforce your main ideas in every passage?

Have you alternated between your voice and the voices of sources? Can you strengthen your voice if it gets trampled by a herd of sources?

Have you used your voice to identify and introduce source material before you present it? Have you used your voice to explain or interpret source material after you include it?

Have you used your voice to tell readers why your sources are relevant, how they support your points, and what their limits might be?

Have you carefully created your voice as a college writer, balancing passion and personality with rock-solid reasoning?

Whenever you are uncertain about the answers to these questions, make an electronic copy of your file or print it out. Highlight all of the wording in your own voice in a bright, visible color. Check for the presence and prominence of this highlighting, and then revise the white patches (the material drawn from sources) as needed to strengthen your voice.

Generating Ideas

For more strategies for generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Pin Down Your Working Topic and Your Cluster of Readings. Specify what you’re going to work on. This task is relatively easy if your instructor has assigned the topic and the required set of readings. If not, figure out what limits your instructor has set and which decisions are yours.

Carefully follow any directions about the number or types of sources that you are expected to use.

Instead of hunting only for sources that share your initial views about the topic, look for a variety of reliable and relevant sources so that you can broaden, even challenge, your perspective.

For advice about finding and evaluating academic sources, see sections B and C in the Quick Research Guide.

Consider Your Audience. You are writing for an academic community that is intrigued by your topic (unless your instructor specifies another group). Your instructor’s broad goal probably includes making sure that you are prepared to succeed when you write future assignments, including full research papers. For this reason, you’ll be expected to quote, paraphrase, and summarize information from sources. You’ll also need to introduce—or launch—such material and credit its source, thus demonstrating that you have mastered the essential skills for source-based writing.

In addition, your instructor will want to see your own position emerge from the swamp of information that you are reading. You may feel that your ideas are like a prehistoric creature, dripping as it struggles out of the bog. If so, encourage your creature to wade toward dry land. Jot down your own ideas whenever they pop into mind. Highlight them in color on the page or on the screen. Store them in your writing notebook or a special file so that you can find them, watch them accumulate, and give them well-deserved prominence in your paper.

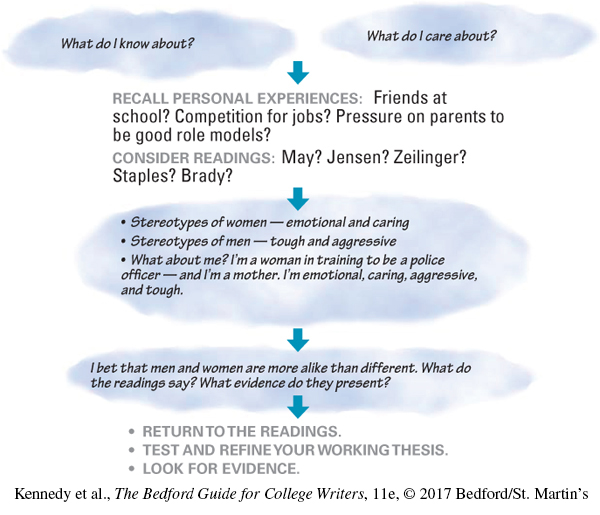

One Student Thinking through a Topic

General subject: Gender

Assigned topic: State and support a position about differences in the behavior of men and women.

Take an Academic Approach. Your experience and imagination are one deep well from which you can draw ideas whenever you need them. For an academic paper, this deep well may help you identify an intriguing topic, raise a compelling question about it, or pursue an unusual slant. For example, you might recall talking with your cousin about her expensive prescriptions and decide to investigate the controversy about importing low-cost medications from other countries.

For more on reading critically, see Ch. 2.

You’ll also be expected to investigate your topic using authoritative sources. These sources—articles, essays, reports, books, Web pages, and other reliable materials—are your second deep well. When one well runs dry for the moment, start pumping the other. As you read critically to tap this second resource, you join the academic exchange. This exchange is the flow of knowledge from one credible source to the next as writers and researchers raise questions, seek answers, evaluate information, and advance knowledge. As you inquire, you’ll move from what you already know to deeper knowledge. Welcome sources that shed light on your inquiry from varied perspectives rather than simply agree with a view you already hold.

Learning by Doing Identifying Suspect Web Information

Learning by Doing Identifying Suspect Web Information

Identifying Suspect Web Information

Examine one of the following Web sites:

Begin with a short summary of the site’s content. Are you persuaded by the arguments presented? Why, or why not? What types of support did you find convincing or weak? Why? Next, look up the tree octopus or dihydrogen monoxide on the hoax-alert Web site snopes.com. What does the Snopes information suggest about the content of the “zapatopi” and “dhmo” sites? What do your findings tell you about how to identify and avoid unreliable Web content?

Skim Your Sources. When you work with a cluster of readings, you’ll probably need to read them repeatedly. Start out, however, by skimming—quickly reading only enough to find out what direction a selection takes.

Leaf through the reading; glance at any headings or figure labels.

Return to the first paragraph; read it in full. Then read only the first sentence of each paragraph. At the end, read the final paragraph in full.

Stop to consider what you’ve already learned.

Do the same with your other selections, classifying or comparing them as you begin to think about what they might contribute to your paper.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

What topic is assigned or under consideration? What ideas about it emerge as you brainstorm, freewrite, or use another strategy to generate ideas?

What cluster of readings will you begin with? What do you already know about them? What have you learned about them simply by skimming?

What purpose would you like to achieve in your paper? Who is your primary audience? What will your instructor expect you to accomplish?

What clues about how to proceed can you draw from the two sample essays in this chapter or from other readings identified as useful models?

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

Start with a Working Thesis. Sometimes you start reading for a source-based paper with a clear position in mind; other times, you begin simply with your initial response to your sources. Either way, try to state your main idea as a working thesis even if you expect to rewrite it—or replace it—later on. Once your thesis takes shape in words, you can assess the richness and relevance of your reading based on a clear main idea.

| FIRST RESPONSETO SOURCES | Joe Robinson, author of “Four Weeks Vacation,” and others say that workers need more vacation time, but I can’t see my boss agreeing to this. |

| WORKING THESIS | Although most workers would like longer vacations, many employers do not believe that they would benefit, too. |

Sometimes a thesis statement for a position paper will push back against common perceptions or stereotypes. This is the approach that Abigail Marchand and Charles M. Blow used for their thesis statements.

| MARCHAND’S THESIS | It is unfortunate that we as a human race allow our own petty ideals to interfere with these simple needs. |

| BLOW’S THESIS | There is an astounding amount of mythology loaded into this stereotype, one that echoes a history of efforts to rob black masculinity of honor and fidelity. |

Learning by Doing Questioning Your Thesis to Aid Your Search for Evidence

Learning by Doing Questioning Your Thesis to Aid Your Search for Evidence

Questioning Your Thesis to Aid Your Search for Evidence

Critically evaluating a working thesis can be a good first step in planning your search for supporting evidence—or for additional evidence if this thesis is based on some initial reading. A student writer asked the following questions about the working thesis statement on longer vacations. Try asking similar questions about your own working thesis to develop an evidence-gathering strategy. Keep these questions, your answers to them, and your notes about evidence gathering handy as you search for sources.

| Questions | Answers | Implications forEvidence Search |

| What parties are involved in the subject or controversy? | Workers and employers | The writer should search for evidence that reflects the concerns of both of these parties. |

| What views might these parties hold on the subject or controversy? | Workers will probably be in favor of longer vacations. Employers will probably be concerned about the costs of increasing vacation days, though it’s possible that such a policy could increase workers’ morale and productivity. | The writer should look for evidence that tests these assumptions, not just supports them. |

| What other parties or factors do I need to consider? | The larger impact of longer vacations. Would they be good for the economy? Bad? Neutral? | The writer should investigate sources that can answer such questions. |

Bear in mind that often material that questions your initial view of a topic proves more valuable than evidence that supports it, prompting you to rethink your thesis, refine it, or counter more effectively whatever challenges it.

Read Each Source Thoughtfully. Before you begin copying quotations, scribbling notes, or highlighting a source, simply read, slowly and carefully. After you have figured out what the source says, you are ready to decide how you might use its information to support your ideas. Read again, this time sifting and selecting what’s relevant to your thesis.

How does the source use its own sources to support its position?

Does it review major sources chronologically (by date), thematically (by topic), or by some other method?

Does it use sources to supply background for its own position? Does it compare its position or research findings with those of other studies?

What audience does the source address? What was its author’s purpose?

How might you want to use the source?

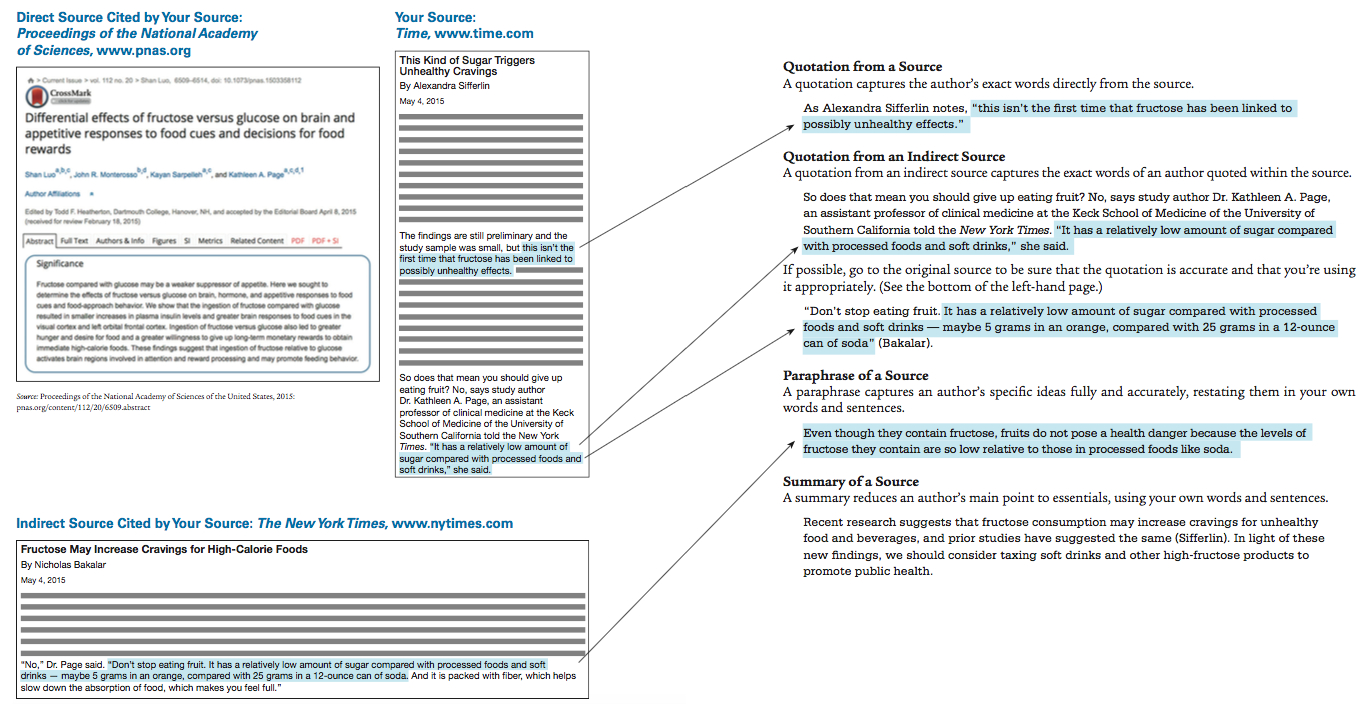

Join the Academic Exchange. A well-researched article that follows academic conventions will identify its sources for several reasons. It gives honest credit to the work on which it relies—work done by other researchers and writers. They deserve credit because their information contributes to the article’s credibility and substantiates its points. The article also informs you about its sources so you, or any other reader, could find them yourself.

The visual below illustrates how this exchange of ideas and information works and how you join this exchange from the moment you begin to use sources in your college writing. The middle of the visual shows the opening of a sample article about the health dangers of one type of sugar: fructose. Because this article appears online, it credits its sources by providing a link to each one. A comparable printed article might identify its sources by supplying brief in-text citations (in parentheses in MLA or APA style), footnotes, numbers keyed to its references, or source identifications in the text itself. To the left of and below the source article are two of its sources. The column to the right of the source article illustrates ways that you might capture information from the source.

For more on plagiarism, see section D in the Quick Research Guide.

Capture Information and Record Source Details. Consider how you might eventually want to capture each significant passage or point from a source in your paper—by quoting the exact words of the source, by paraphrasing its ideas in your own words, or by summarizing its essential point. Keeping accurate notes and records as you work with your sources will help you avoid accidental plagiarism (using someone else’s words or ideas without giving the credit due). Accurate notes also help to reduce errors or missing information when you add the source material to your draft.

For more on citing and listing sources, see section E in the Quick Research Guide.

As you capture information, plan ahead so that you can acknowledge each source following academic conventions. Record the details necessary to identify the source in your discussion and to list it with other sources at the end of your paper.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Plagiarism

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Plagiarism

Reflecting on Plagiarism

You have worked hard on a group presentation that will be a major part of your grade—and each member of the group will get the same grade. Two days before the project is due, you discover that one group member has plagiarized heavily from sources well known to your instructor. First, research your institution’s policy on plagiarism. Now check your syllabus. Is there a stated policy on plagiarism for the course? If so, are there differences between the policy of your institution and the policy of your class? Explain the consequences for each. Do you think there are circumstances that would make plagiarism acceptable under either or both policies? If so, describe them. Why do you think students plagiarize? Do you think it has to do with writing ability, or with something else? What about purchasing an essay? Is that a form of plagiarism? Have you ever plagiarized (accidentally or intentionally)? What were the circumstances? What would you do differently today?

The next sections illustrate how to capture and credit your sources, using examples for a paper that connects land use and threats to wildlife. Compare the examples with the original passage from the source.

Identify Significant Quotations. When an author expresses an idea so memorably that you want to reproduce those words exactly, quote them word for word. Direct quotations can add life, color, and authority; too many can drown your voice and overshadow your point.

| ORIGINAL | The tortoise is a creature that has survived virtually unchanged since it first appeared in the geologic record more than 150 million years ago. The species became threatened, however, when ranchers began driving their herds onto Mojave Desert lands for spring grazing, at the very time that the tortoise awakens from hibernation and emerges from its burrows to graze on the greening desert shrubs and grasses. As livestock trampled the burrows and monopolized the scarce desert vegetation, tortoise populations plummeted. (page 152) |

|

Babbitt, Bruce. Cities in the Wilderness: A New Vision of Land Use in America. Island Press-Shearwater, 2005. |

|

| TOO MUCH QUOTATION | When “tortoise populations plummeted,” a species “that has survived virtually unchanged since it first appeared in the geologic record more than 150 million years ago” (Babbitt 152) had losses that helped to justify setting workable boundaries for the future expansion of Las Vegas. |

| MEMORABLE QUOTATION | When “tortoise populations plummeted” (Babbitt 152), an unlikely species that has endured for millions of years helped to establish workable boundaries for the future expansion of Las Vegas. |

ACADEMIC EXCHANGE Suppose that you used the article “This Kind of Sugar Triggers Unhealthy Cravings” (excerpted on the right), to support a position. In turn, your source drew on other writings, two of which are excerpted to the left of and below the article. The various ways you might use this source are shown on the right-hand page.

Information Captured from Your Source

Sample Working Thesis

A clear thesis statement establishes a framework for selecting source material as useful evidence and for explaining its relevance to readers.

| WORKING THESIS | Given growing evidence of the health dangers of high-fructose food and beverages, it is time to think about taxing these items to help discourage their use. |

MLA Works Cited Entry

Writers often begin by highlighting or copying too many quotations as they struggle to master the ideas in the source. The better you understand the reading and your own thesis, the more effectively you’ll choose quotations. After all, a quotation in itself is not necessarily effective evidence; too many quotations suggest that your writing is padded or lacks originality.

For more on quotations, see section D in the Quick Research Guide.

HOW TO QUOTE

Select a quotation that is both notable and pertinent to your thesis.

Record it accurately, writing out exactly what it says. Include its punctuation and capitalization. Avoid abbreviations that might later be ambiguous.

Mark both its beginning and ending with quotation marks.

Note the page or other location where the quotation appears. If the quotation begins on one page but ends on another, mark where the switch occurs so that the credit in your draft will be accurate no matter how much of the quotation you eventually use.

Double-check the accuracy of each quotation as you record it.

For more on punctuating quotations and using ellipsis marks, see section D in the Quick Editing Guide.

Use an ellipsis mark—three spaced dots (. . .) within a sentence or four dots (. . . .), a period and three spaced dots, concluding a sentence—to show where you leave out any original wording. You may omit wording that doesn’t relate to your point, but don’t distort the original meaning. For example, if a reviewer calls a movie “a perfect example of poor directing and inept acting,” don’t quote this comment as “perfect . . . directing and . . . acting.”

Paraphrase Specific Information. Paraphrasing involves restating an author’s ideas in your own language. A paraphrase is generally about the same length as the original. It conveys the ideas and emphasis of the original in your words and sentences, thus bringing your own voice to the fore. A fresh and creative paraphrase expresses your style without awkwardly jumping between it and your source’s style. Be sure to name the source so that your reader knows exactly where you move from one to the other.

Here, again, is the original passage by Bruce Babbitt, followed by a sloppy paraphrase. The paraphrase suffers from a common fault, slipping in too many words from the original. (The borrowed words are underlined in the paraphrase.) Those words need to be expressed in the writer’s own language or identified as direct quotations with quotation marks.

| ORIGINAL | The tortoise is a creature that has survived virtually unchanged since it first appeared in the geologic record more than 150 million years ago. The species became threatened, however, when ranchers began driving their herds onto Mojave Desert lands for spring grazing, at the very time that the tortoise awakens from hibernation and emerges from its burrows to graze on the greening desert shrubs and grasses. As livestock trampled the burrows and monopolized the scarce desert vegetation, tortoise populations plummeted. (page 152) |

|

Babbitt, Bruce. Cities in the Wilderness: A New Vision of Land Use in America. Island Press-Shearwater, 2005. |

|

| SLOPPY PARAPHRASE | Babbitt says that the tortoise is a creature in the Mojave that is virtually unchanged over 150 million years. Over the millennia, the tortoise would awaken from hibernation just in time for spring grazing on the new growth of the region’s shrubs and grasses. In recent years the species became threatened. When cattle started to compete for the same food, the livestock trampled the tortoise burrows and monopolized the desert vegetation while the tortoise populations plummeted (152). |

To avoid picking up language from the original as you paraphrase, state each sentence afresh instead of just changing a few words in the original. If possible, take a short break, and then check each sentence against the original. Highlight any identical words or sentence patterns, and rework your paraphrase again. Proper nouns or exact terms for the topic (such as tortoise) do not need to be rephrased.

The next example avoids parroting the original by making different word choices while reversing or varying sentence patterns.

| PARAPHRASE | As Babbitt explains, a tenacious survivor in the Mojave is the 150-million-year-old desert tortoise. Over the millennia, the hibernating tortoise would rouse itself each spring just in time to enjoy the new growth of the limited regional plants. In recent years, as cattle became rivals for this desert territory, the larger animals destroyed tortoise homes, ate tortoise food, and thus eliminated many of the tortoises themselves (152). |

A common option is to blend paraphrase with brief quotation, carefully using quotation marks to identify any exact words drawn from the source.

| BLENDED | Babbitt describes a tenacious survivor in the Mojave, the 150-million-year-old desert tortoise. Over the millennia, the hibernating tortoise would rouse itself each spring just in time to munch on the new growth of the sparse regional plants. As cattle became rivals for the desert food supply and destroyed the tortoise homes, the “tortoise populations plummeted” (152). |

Even in a brief paraphrase, be careful to avoid slipping in the author’s words or closely shadowing the original sentence structure. If a source says, “the president called an emergency meeting of his cabinet to discuss the crisis,” and you write, “The president called his cabinet to hold an emergency meeting to discuss the crisis,” your words are too close to those of the source. One option is to quote the original, though it doesn’t seem worth quoting word for word. Or, better, you could write, “Summoning his cabinet to an immediate session, the president laid out the challenge before them.”

For more on paraphrases, see section D in the Quick Research Guide.

HOW TO PARAPHRASE

Select a passage with detailed information relevant to your thesis.

Reword the passage: represent it accurately but use your own language.

Change both its words and its sentence patterns. Replace its words with different expressions. Begin and end sentences differently, simplify long sentences, and reorder information.

Note the page or other location where the original appears in your source. If the passage runs from one page onto the next, record where the page changes so that your credit will be accurate no matter how much of the paraphrase you use.

After a break, recheck your paraphrase against the original to be certain that it does not repeat the same words or merely replace a few with synonyms. Revise as needed, placing fresh words in fresh arrangements.

For advice on writing a synopsis of a literary work, see Learning from Another Writer: Synopsis in Ch. 13.

Summarize an Overall Point. Summarizing is a useful way of incorporating the general point of a whole paragraph, section, or work. You briefly state the main sense of the original in your own words and also identify the source. Like a paraphrase, a summary uses your own language. However, a summary is shorter than the original; it expresses only the most important ideas—the essence—of the original. This example summarizes the section of Babbitt’s book containing the passage quoted above.

| SUMMARY | According to Bruce Babbitt, former Secretary of the Interior and governor of Arizona, the isolated federal land in the West traditionally has been open to cattle and sheep ranching. These animals have damaged the arid land by grazing too aggressively, and the ranchers have battled wildlife grazers and predators alike to reduce competition with their stock. Protecting species such as the gray wolf and the desert tortoise has meant limiting grazing, an action supported by the public in order to conserve the character and beauty of the public land. |

For more on summaries, see section D in the Quick Research Guide.

HOW TO SUMMARIZE

Select a passage, an article, a chapter, or an entire book whose main idea bears on your thesis.

Read the selection carefully until you have mastered its overall point.

Write a sentence or a series of sentences that states its essence in your own words.

Revise your summary until it is as concise, clear, and accurate as possible. Replace any vague generalizations with precise words.

Name your source as you begin your summary, or identify it in parentheses.

| Quotation | Paraphrase | Summary | |

| Format for Wording | Use exact words from the source, and identify any additions, deletions, or other changes | Use your words and sentence structures, translating the content of the original passage | Use your words and sentence structures, reducing the original passage to its core |

| Common Use | Capture lively and authoritative wording | Capture specific information while conserving its detail | Capture the overall essence of an entire source or a passage in brief form |

| Advantages | Catch a reader’s attention Emphasize the authority of the source |

Treat specifics fully without shifting from your voice to the source’s | Make a broad but clear point without shifting from your voice to the source’s |

| Common Problems | Quoting too much Quoting inaccurately |

Slipping in the original wording Following the original sentence patterns too closely |

Losing impact by bogging down in too much detail Drifting into vague generalities |

| Markers | Identify source in launch statement or text citation and in final list of sources Add quotation marks to show the source’s exact words Use ellipses and brackets to mark any changes |

Identify source in launch statement or text citation and in final list of sources | Identify source in launch statement or text citation and in final list of sources |

Credit Your Sources Fairly. As you quote, paraphrase, or summarize, be certain to note which source you are using and exactly where the material appears in the original. Carefully citing and listing your sources will give credit where it’s due as it enhances your credibility as a careful writer.

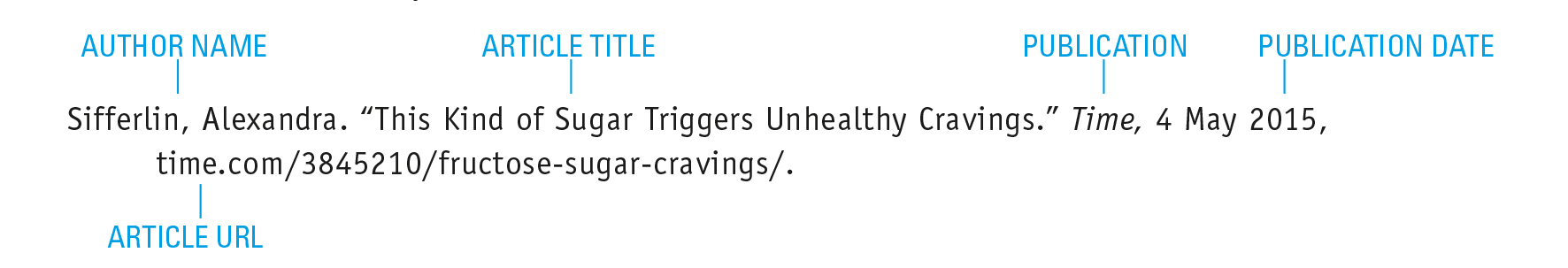

Although academic fields prefer specific formats for their papers, MLA style is widely used in composition, English, and other humanities courses. In MLA style, you credit your source twice. First, identify the author’s last name (and the page number in the original) in the text as you quote, paraphrase, summarize, or refer to the source. Often you will simply mention the author’s name (or a short version of the title if the author is not identified) as you introduce the information from the source. If not, note the name and page number of the original in parentheses after you present the material: (Walton 88). Next, fully identify the source in an alphabetical list at the end of your paper.

For sample source citations and lists, see Learning from Other Writers and the MLA and APA examples in section E in the Quick Research Guide, and in section A in the Quick Format Guide.

Right now, the methods for capturing information and crediting sources may seem complicated. However, the more you use them, the easier they become. Experienced writers also know some time-tested secrets. For example, how can you save time, improve accuracy, and avoid last-minute stress about sources? The answer is easy. Include in your draft, even your very first one, both the source identification and the location. Add them at the very moment when you first add the material, even if you are just dropping it in so you don’t forget it. Later on, you won’t have to hunt for the details.

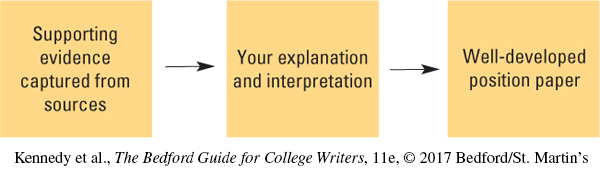

Let Your Draft Evolve. No matter how many quotations, paraphrases, and summaries you assemble, chunks of evidence captured from sources do not—on their own—constitute a solid paper. You need to interpret and explain that evidence for your readers, helping them to see exactly why, how, and to what extent it supports your position.

To develop a solid draft, many writers rely on one of two methods, beginning either with the evidence or with the position they wish to support.

Method 1. Start with your evidence. Use one of these strategies to arrange quotations, paraphrases, and summaries in a logical, compelling order.

Cut and paste the chunks of evidence, moving them around in a file until they fall into a logical order.

Print each chunk on a separate page, and arrange the pages on a flat surface like a table, floor, or bed until you reach a workable sequence.

Label each chunk with a key word, and use the key words to work out an informal outline.

Once your evidence is organized logically, add commentary to connect the chunks for your readers: introduce, conclude, and link pieces of evidence with your explanations and interpretations. (Ignore any leftovers from sources unless they cover key points that you still need to integrate.) Let your draft expand as you alternate evidence and interpretation.

Method 2. Start with your position or your conclusion, selecting a way to focus on how you want your paper to present it.

You can state your case boldly and directly, explaining your thesis and supporting points in your own words.

If you feel too uncertain to take that step, you can write out directions, telling yourself what to do in each part of the draft (in preparation for actually doing it).

Either way, use this working structure to identify where to embed the evidence from your sources. Let your draft grow as you pull in your sources and expand your comments.

DEVELOPMENT CHECKLIST

Have you quoted only notable passages that add support and authority?

Have you checked your quotations for accuracy and marked where each begins and ends with quotation marks?

Have you paraphrased accurately, reflecting both the main points and the supporting details in the original?

Does each paraphrase use your own words without repeating or echoing the words or the sentence structure of the original?

Have you briefly stated supporting ideas that you wish to summarize, sticking to the overall point without bogging down in details or examples?

Has each summary remained respectful of the ideas and opinions of others, even if you disagree with them?

Have you identified the source of every quotation, paraphrase, summary, or source reference by noting in parentheses the last name of the writer and the page number (if available) where the passage appears in the source?

Have you ordered your evidence logically and effectively?

Have you interpreted and explained your evidence from sources with your own comments in your own voice?

Revising and Editing

For more on revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

As you read over the draft of your paper, remember what you wanted to accomplish: to develop an enlightening position about your topic and to share this position with a college audience, using sources to support your ideas.

Strengthen Your Thesis. As you begin revising, you may decide that your working thesis is ambiguous, poorly worded, hard to support, or simply off the mark. Revise it so that it clearly alerts readers to your main idea.

| WORKING THESIS | Although most workers would like longer vacations, many employers do not believe that they would benefit, too. |

| REVISED THESIS | Despite assumptions to the contrary, employers who increase vacation time for workers also are likely to increase creativity, productivity, and the bottom line. |

THESIS CHECKLIST

Is your thesis, or main idea, clear?

Have you made it as specific as possible?

Is it distinguished from the points made by your sources?

Does it take a strong position?

Does it need to be refined or qualified in response to evidence that you’ve gathered or to any rethinking of your original position?

For more about launching sources, see section D in the Quick Research Guide.

Launch Each Source. Whenever you quote, paraphrase, summarize, or refer to a source, launch it with a suitable introduction. An effective launch sets the scene for your source material, prepares your reader to accept it, and marks the transition from your words and ideas to those of the source. As you revise, confirm that you launch all of your source material well.

In a launch statement, often you will first identify the source—by the author’s last name or by a short version of the title when the author isn’t named—in your introductory sentence. If not, identify the source in parentheses, typically to end the sentence. Then try to suggest why you’ve mentioned this source at this point, perhaps noting its contribution, its credibility, its vantage point, or its relationship to other sources. Vary your launch statements to avoid tedium and to add emphasis. Boost your credibility as a writer by establishing the credibility of your sources.

Here are some typical patterns for launch statements:

As Yung demonstrates, . . .

Although Zeffir maintains . . ., Matson suggests . . .

Many schools educated the young but also unified the community (Hill 22). . . .

In Forward March, Smith’s study of the children of military personnel, . . .

Another common recommendation is . . . (“Safety Manual”).

Making good use of her experience as a travel consultant, Lee explains . . .

When you quote or paraphrase from a specific page, include that exact location.

The classic definition of . . . (Bagette 18).

Benton distinguishes four typical steps in this process (248–51).

Learning by Doing Launching Your Sources

Learning by Doing Launching Your Sources

Launching Your Sources

Make a duplicate file of your draft or print it. Add highlights in one color to mark all your source identifications; use another color to mark source material:

The problem of unintended consequences is well illustrated by many environmental changes over recent decades. For instance, if using the Mojave Desert for cattle grazing seemed efficient to ranchers, it also turned out to be destructive for long-time desert residents such as tortoises (Babbitt 152).

Now examine your draft. How do the colors alternate? Do you find color globs where you simply list sources without explaining their contributions? Do you find material without source identification (typically the author’s name) or without a location in the original (typically a page number)? Fill in whatever gaps you discover.

Synthesize Several Sources. Often you will compare, contrast, or relate two or three sources to deepen your discussion or to illustrate a range of views. When you synthesize, you pull together several sources in the same passage to build a new interpretation or reach a new conclusion. You go beyond the separate contributions of the individual sources to relate the sources to each other and to connect them to your thesis. A synthesis should be easy to follow and use your own wording.

HOW TO SYNTHESIZE

Summarize each of the sources you want to synthesize. Boil down each summary to its essence.

Write a few sentences that state in your own words how the sources are linked. For example, are they similar, different, or related? Do they share assumptions and conclusions, or do they represent alternatives, opposites, or opponents? Do they speak to chronology, influence, logical progression, or diversity of opinion?

Write a few more sentences stating what the source relationships mean for your thesis and the position you develop in your paper.

Refine your synthesis statements until they are clear and illuminating for your audience. Embed them as you move from one source summary to the next and as you reach new interpretations or conclusions that go beyond the separate sources.

Use Your Own Voice to Interpret and Connect. By the time your draft is finished, you may feel that you have found relevant evidence in your sources but that they now dominate your draft. As you reread, you may discover passages that simply string together ideas from sources.

DRAFT

|

Writers Lisa Jo Rudy and Giulia Rhodes say that video games, television, and other screen-based activities can benefit children on the autism spectrum. Simon Baron Cohen, a professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge, says: “We can use computers to teach emotion recognition and to simplify communication by stripping out facial and vocal emotional expressions and slowing it down using e-mail instead of face-to-face real-time modes” (Rhodes). Christopher R. Engelhardt, a researcher at the University of Missouri-Columbia, says, “In-room media access was associated with about 1.5 fewer hours of sleep per night in the group with autism” (Doyle). |

Whole passage repeats “say”/ “says” Jumps from one source to the next without explanations or transitions |

When your sources overshadow your thesis, your explanations, and your writing style, revise to restore balance. Try strategies such as these to regain control of your draft:

Add your explanation and interpretation of the source information so that your ideas are clear.

Add transitions, and state the connections that you assume are obvious.

Arrange information in a logical sequence, not in the order in which you read it or recorded notes about it.

Clarify definitions, justify a topic’s importance, and recognize alternative views to help your audience appreciate your position.

Reword to vary your sentence openings, and avoid repetitive wording.

Thoughtful revision can help readers grasp what you want to say, why you have included each source, and how you think that it supports your thesis.

REVISION

|

As the parent of a child on the autism spectrum, I have long questioned whether I should limit my son’s screen time in some way. Based on my recent research, I have concluded that it is probably beneficial to allow him to play video games, one of his favorite activities, but that I should place some restrictions on his access to them. Page 241

Clearly, playing video games, watching television, and participating in other screen-based activities can provide certain benefits for children on the autism spectrum. For example, these activities can aid these children’s learning, help them connect with peers, and give them a greater sense of control over their environment (Rudy, Rhodes). Simon Baron Cohen, a professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge, has noted the benefits of computers to people with autism: “We can use computers to teach emotion recognition and to simplify communication by stripping out facial and vocal emotional expressions and slowing it down using e-mail instead of face-to-face real-time modes” (Rhodes). However, unrestricted screen access is not without drawbacks. Recently, for example, a group of researchers at the University of Missouri-Columbia found that boys on the autism spectrum who had bedtime access to television, computers, and video games slept less each night (Engelhardt, Mazurek, and Sohl). According to Christopher R. Engelhardt, the researcher who led the study, “In-room media access was associated with about 1.5 fewer hours of sleep per night in the group with autism” (Doyle). |

Identifies author’s experience to add to credibility; draws conclusions based on her research Adds a transition and introduces a summary Introduces a quotation Adds more transitions and introduces additional source material |

List Your Sources as College Readers Expect. When you use sources in a college paper, you’ll be expected to identify them twice: briefly when you draw information from them and fully when you list them at the end of your paper, following a conventional system. The list of sources for the draft and revision in the previous section would include these entries.

Doyle, Kathryn.“Bedroom Computers, TV May Add to Autism Sleep Issues.” Reuters, 18 Nov. 2013, www.reuters.com/

Engelhardt, Christopher R., et al.“Media Use and Sleep Among Boys with Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, or Typical Development.” Pediatrics, vol. 132, no. 6, Dec. 2013, pp. 1081–89.

Rhodes, Giulia.“Autism: How Computers Can Help.” TheGuardian.com, 26 Feb. 2012, www.theguardian.com/

Rudy, Lisa Jo.“Top 10 Good Reasons for Allowing Autistic Children to Watch TV and Videos.” About.com, 13 May 2015, autism.about.com/

Learning by Doing Checking Your Presentation of Sources

Learning by Doing Checking Your Presentation of Sources

Checking Your Presentation of Sources

Use your software to improve the presentation of source materials in your draft. For example, search for all quotation marks in your paper. Make sure that each is one of a pair surrounding every quotation. Also, be sure each quotation’s source and location are identified. Try color highlighting in your final list of sources to help you spot and refine details, especially common personal errors. For instance, if you forget periods after names of authors or mix up semicolons and colons, highlight those marks so you slow down and focus on them. Then correct or add marks as needed. After you check your entries, remove the highlighting.

Use the Take Action chart below to figure out how to improve your draft. Skim the left-hand column to identify questions you might ask about integrating sources in your draft. When you answer a question with “Yes” or “Maybe,” move straight across to Locate Specifics for that question. Use the activities there to pinpoint gaps, problems, or weaknesses. Then move straight across to Take Action. Use the advice that suits your problem as you revise.

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Supporting a Position with Sources

Peer Response Supporting a Position with Sources

Supporting a Position with Sources

Have several classmates read your draft critically, considering how effectively you have used your sources to support a position. Ask your peer editors to answer questions such as these:

Can you state the writer’s position on the topic?

Do you have any trouble seeing how the writer’s points and the supporting evidence from sources connect? How might the writer make the connections clearer?

How effectively does the writer capture the information from sources? Would you recommend that any of the quotations, paraphrases, or summaries be presented differently?

Are any of the source citations unclear? Can you tell where source information came from and where quotations and paraphrases appear in a source?

Is the writer’s voice clear? Do the sources drown it out in any spots?

If this paper were yours, what is the one thing you would be sure to work on before handing it in?

Take Action Integrating Source Information Effectively

Ask each question listed in the left-hand column to determine whether your draft might need work on that issue. If so, follow the ASK—LOCATE SPECIFICS—TAKE ACTION sequence to revise.

| 1 ASK | 2 LOCATE SPECIFICS | 3 TAKE ACTION |

| Have I tossed in source material without preparing my audience for it? Do I repeat the same words in my launch statements? |

|

|

| Is my own voice lost? Have I allowed my sources to take over my draft? Have I strung together too many quotations? |

|

|

| Have I identified a source only once or twice even though I use it throughout a section? |

|

|

REVISION CHECKLIST

Do you speak in your own voice, interpreting and explaining your sources instead of allowing them to dominate your draft?

Have you moved smoothly back and forth between your explanations and your source material?

Have you credited every source in the text and in a list at the end of your paper? Have you added each detail expected in the format for listing sources?

Have you been careful to quote, paraphrase, summarize, and credit sources accurately and ethically? Have you hunted up missing details, double-checked quotations, and rechecked the accuracy of anything prepared hastily?

After you have revised your paper, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems you find. Be certain to check the punctuation with your quotations, making sure that each quotation mark is correctly placed and that you have used other punctuation, such as commas, correctly.

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide. Also see to the Quick Format Guide.

EDITING CHECKLIST

A4Do all the verbs agree with their subjects, especially when you switch from your words to those of a source?

A6Do all the pronouns agree with their antecedents, especially when you use your words with a quotation from a source?

C1Have you used commas correctly, especially where you integrate material from sources?

C3Have you punctuated all your quotations correctly?