Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Observing a Scene

Observe a place near your campus, home, or job and the people who frequent it. Then write a paper that describes the place, the people, and their actions so as to convey the spirit of the place and offer some insight into its impact on the people.

This assignment is meant to start you observing closely enough that you go beyond the obvious. Go somewhere nearby, and station yourself where you can mingle with the people there. Open all your senses so that you see, smell, taste, hear, and feel. Jot down what you immediately notice, especially the atmosphere and its effect on the people there. Take notes describing the location, people, actions, and events you see. Then use your observations to convey the spirit of the scene. What is your main impression of the place? Of the people there? Of the relationship between people and place? Your purpose is not only to describe the scene but also to express thoughts and feelings connected with what you observe.

Three student writers wrote about these observations:

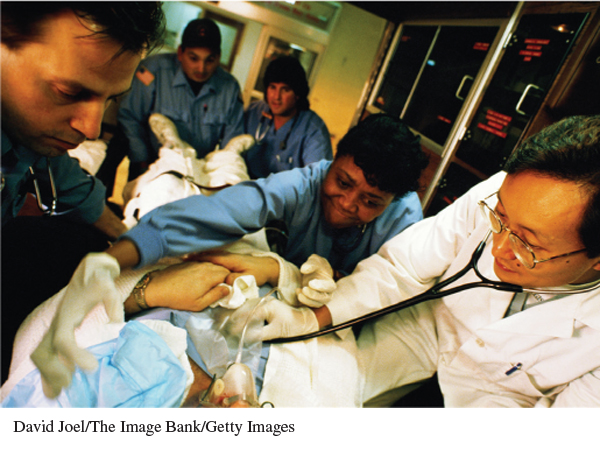

One student, who works nights in the emergency room, observed the scene and the community that abruptly forms when an accident victim arrives: medical staff, patient, friends, and relatives.

Another observed a bar mitzvah celebration that reunited a family for the first time in many years.

Another observed the activity in the stands in a stadium before, during, and after a soccer game.

When you select the scene you wish to observe, find out from the person in charge whether you’ll need to request permission to observe there, as you might at a school, a business, or another restricted or privately owned site.

Facing the Challenge Observing a Scene

The major challenge writers face when writing from observation is to select compelling details that convey an engaging main impression of a scene. As we experience the world, we’re bombarded by sensory details, but our task as writers is to choose those that bring a subject alive for readers. For example, describing an oak as “a big tree with green leaves” is too vague to help readers envision the tree or grasp its unique qualities. Consider:

What colors, shapes, and sizes do you see?

What tones, pitches, and rhythms do you hear?

What textures, grains, and physical features do you feel?

What fragrances and odors do you smell?

What sweet, spicy, or other flavors do you taste?

After recording the details that define the scene, ask two more questions:

What overall main impression do these details establish?

Which specific details will best show the spirit of this scene to a reader?

Your answers will help you decide which details to include in your paper.

Generating Ideas

For more on each strategy for generating ideas in this section or for additional strategies, see Ch. 19.

Although setting down observations might seem cut-and-dried, to many writers it is true discovery. Here are some ways to generate such observations.

Brainstorm. First, choose a scene to observe. What places interest you? Which are memorable? Start brainstorming—listing rapidly any ideas that come to mind. Here are a few questions to help you start your list:

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

Where do people gather for some event or performance (a stadium, a place of worship, a theater, an auditorium)?

Where do people meet for some activity (a gym, a classroom)?

- Page 75

Where do crowds form while people are getting things or services (a shopping mall, a dining hall or student union, a dentist’s waiting room)?

Where do people pause on their way to yet another destination (a light-rail station, a bus or subway station, an airport, a restaurant on the toll road)?

Where do people go for recreation or relaxation (an arcade, a ballpark)?

Where do people gather (a party, a wedding, a graduation, an audition)?

Get Out and Look. If nothing on your list strikes you as compelling, plunge into the world to see what you see. Visit a city street or country hillside, a student event or practice field, a contest, a lively scene—a mall, an airport, a fast-food restaurant, a student hangout—or a scene with only a few people sunbathing, walking dogs, or playing basketball. Observe for a while, and then mix and move to gain different views.

Record Your Observations. Alea Eyre’s essay “Stockholm” began with some notes about her vivid memories of her trip. She was able to mine those memories for details to bring her subject to life.

Your notes on a subject—or tentative subject—can be taken in any order or methodically. To draw up an “observation sheet,” fold a sheet of paper in half lengthwise. Label the left column “Objective,” and impartially list what you see, like a zoologist looking at a new species of moth. Label the right column “Subjective,” and list your thoughts and feelings about what you observe. The quality of your paper will depend in large part on the truthfulness and accuracy of your observations. Your objective notes will trigger more subjective ones.

| Objective | Subjective |

| The ticket holders form a line on the weathered sidewalk outside the old brick hall, standing two or three deep all the way down the block. | This place has seen concerts of all kinds—you can feel the history as you wait, as if the hall protects the crowds and the music. |

| Groups of friends talk, a few couples hug, and some guys burst out in staccato laughter as they joke. | The crowd seems relaxed and friendly, all waiting to hear their favorite group. |

| Everyone shuffles forward when the doors open, looking around at the crowd and edging toward the entrance. | The excitement and energy grow with the wait, but it’s the concert ritual—the prelude to a perfect night. |

Include a Range of Images. Have you captured not just sights but sounds, textures, odors? Have you observed from several vantage points or on several occasions to deepen your impressions? Have you added sketches or doodles to your notes, perhaps drawing the features or shape of the place? Can you begin writing as you continue to observe? Have you noticed how other writers use images, evoking sensory experience, to record what they sense? In the memoir Northern Farm, naturalist Henry Beston describes a remarkable sound: “the voice of ice,” the midwinter sound of a whole frozen pond settling and expanding in its bed.

Sometimes there was a sort of hollow oboe sound, and sometimes a groan with a delicate undertone of thunder. . . . Just as I turned to go, there came from below one curious and sinister crack which ran off into a sound like the whine of a giant whip of steel lashed through the moonlit air.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Sensory Details

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Sensory Details

Reflecting on Sensory Details

Step outside with your notebook. Take a deep breath and observe your surroundings. Writing as quickly as you can for five minutes, create a list of sensory details (what you see, hear, smell, feel, and so on). Return to the classroom and write a reflection paragraph that describes your experience using the sensory details you recorded.

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

After recording your observations, look over your notes, circling whatever looks useful. Maybe you can rewrite your notes into a draft, throwing out details that don’t matter, leaving those that do. Maybe you’ll need a plan to help you organize all the observations, laying them out graphically or in a simple scratch outline.

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

Start with a Main Impression or Thesis. What main insight or impression do you want to convey? Answering this question will help you decide which details to include, which to omit, and how to avoid a dry list of facts.

| PLACE OBSERVED | Smalley Green after lunch |

| MAIN IMPRESSION | relaxing activity is good after a morning of classes |

| WORKING THESIS | After their morning classes, students have fun relaxing on Smalley Green with their dogs and Frisbees. |

If all the details that you’ve gathered seem to be overwhelming your ability to arrive at a main impression, take a break (and maybe a walk) and try to think of a statement that sums things up. One good example of a summary statement is Alea Eyre’s “As soon as I stepped off the plane ramp, I was enveloped into a brand new world.”

For more organization strategies, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

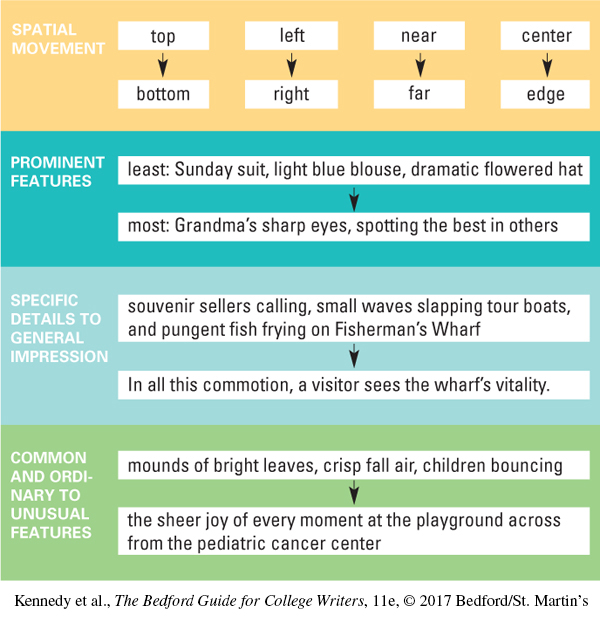

Organize to Show Your Audience Your Point. How do you map out a series of observations? Your choice depends on your purpose and the main impression you want to create. Whatever your choice, add transitions—words or phrases to guide the reader from one vantage point, location, or idea to the next.

For transitions that mark place or direction, see Adding Cues and Connections in Ch. 21.

As you create your “picture,” you bring a place to life using the details that capture its spirit. If your instructor approves, consider whether adding a photograph, sketch, diagram, or other illustration—with a caption—would enhance your written observation.

Learning by Doing Experimenting with Organization

Learning by Doing Experimenting with Organization

Experimenting with Organization

Take a second look at the arrangement of the details in your observation. Select a different yet promising sequence, and test it by outlining your draft in that order. Ask classmates for reactions as you consider which sequence most effectively conveys your main impression.

Revising and Editing

For more revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

Your revising, editing, and proofreading will be easier if you have accurate notes on your observations. But what if you don’t have enough detail for your draft? If you have doubts, go back to the scene to take more notes.

Focus on a Main Impression or Thesis. As you begin to revise, have a friend read your observation, or read it yourself as if you had never seen the place you observed. Note gaps that would puzzle a reader, restate the spirit of the place, or sharpen the description of the main impression you want to convey in your thesis.

| WORKING THESIS | After morning classes, students have fun relaxing on Smalley Green with their dogs and Frisbees. |

| REVISED THESIS | When students, dogs, and Frisbees accumulate on Smalley Green after lunch, they show how much campus learning takes place outside of class. |

THESIS CHECKLIST

Does thesis convey your main impression?

Does thesis (and the essay) offer an insight into the subject that you are observing?

Could you make thesis more vivid or specific based on details or insights you’ve gathered while planning, drafting, and developing your essay?

Learning by Doing Strengthening Your Main Impression

Learning by Doing Strengthening Your Main Impression

Strengthening Your Main Impression

Complete these two sentences: The main impression that I want to show my audience is ________. The main insight that I want to share is _________. Exchange sentences with a classmate or small group, and then each read aloud that draft while the others listen for the impression and insight the writer wants to convey. After each reading, discuss with the writer cuts, additions, and other changes to strengthen that impression.

Add Relevant and Powerful Details. Next, check your selection of details. Does each detail contribute to your main impression? Should any be dropped or added? Should any be rearranged so that your organization, moving point to point, is clearer? Could some observations be described more vividly, powerfully, or concretely? Could vague words such as very, really, great, or beautiful be replaced with more specific words? (Use Find to locate repetition, so you can reword for variety.)

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Observing a Scene

Peer Response Observing a Scene

Observing a Scene

Let a classmate or friend respond to your draft, suggesting how to use detail to convey your main impression more powerfully. Ask your peer editor to answer questions such as these about writing from observation:

What main insight or impression do you carry away from this draft?

Which sense does the writer use particularly well? Are any senses neglected?

Can you see and feel what the writer experienced? Would more detail be more compelling? Put check marks wherever you want more details.

How well has the writer used evidence from the senses to build a main impression? Which sensory impressions contribute most strongly to the overall picture? Which seem superfluous?

If this paper were yours, what one thing would you work on?

To see where your draft could need work, consider these questions:

REVISION CHECKLIST

Have you accomplished your purpose—to convey to readers your overall impression of your subject and to share some telling insight about it?

What can you assume your readers know? What do they need to be told?

Page 80Have you gathered enough observations to describe your subject? Have you observed with all your senses when possible—even smell and taste?

Have you been selective, including details that effectively support your overall impression?

Which observations might need to be checked for accuracy? Which might need to be checked for richness or fullness?

Is your organizational pattern the most effective for your subject? Is it easy for readers to follow? Would another pattern work better?

For more on editing and proofreading strategies, see Editing and Proofreading in Ch. 23.

After you revise your essay, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems. If you added details, consider whether they’re sufficiently blended with the ideas already there. Some questions to get you started:

EDITING CHECKLIST

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide and Quick Format Guide.

A7Have you used an adjective when you describe a noun or pronoun? Have you used an adverb when you describe a verb, adjective, or adverb? Have you used the correct form to compare two or more things?

B1Is it clear what each modifier in a sentence modifies? Have you created any dangling or misplaced modifiers?

B2Have you used parallel structure wherever needed, especially in lists or comparisons?