Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Explaining Causes and Effects

Pick a disturbing fact or situation that you have observed, and seek out its causes and effects to help you and your readers understand the issue better. You may limit your essay to the causes or the effects, or you may include both but emphasize one more than the other. Yun Yung Choi uses the last approach when she identifies the cause of the status of Korean women (Confucianism) but spends most of her essay detailing effects of this cause.

The situation you choose may have affected you and people you know well, such as student loan policies, the difficulty of working while going to school, or a challenge facing your family. It might have affected people in your city or region—a small voter turnout in an election, decaying bridge supports, or dog owners not picking up their pets’ waste. It may affect society at large—identity theft, immigration laws, or the high cost of health care. It might be gender or racial stereotypes on television, binge drinking, teenage suicide, climate change, or student debt. Don’t think you must choose an earthshaking topic to write a good paper. On the contrary, you will do a better job if you are personally familiar with the situation you choose.

These students selected topics of personal concern for causal analysis:

One student cited her observations of the hardships faced by Indians in rural Mexico as one cause of rebellions there.

Another analyzed the negative attitudes of men toward women at her workplace and the resulting tension, inefficiency, and low production.

A third contended that buildings in Miami are not constructed to withstand hurricanes due, in part, to an inadequate inspection system.

Facing the Challenge Causes and Effects

The major challenge writers face when exploring causal relationships is how to limit the subject. When you explore a given phenomenon—whether local unemployment or the success of your favorite band—devoting equal space to all possible causes and effects will either overwhelm your readers or put them to sleep. Instead, you need to decide what you want to show your readers—and then emphasize the causal relationships that help achieve this purpose.

Rely on your purpose to help you decide which part of the relationship—cause or effect—to stress and how to limit your ideas to strengthen your overall point. If you are writing about your family’s financial stresses, for example, you may be tempted to discuss all the possible causes and then analyze all the effects the stresses have had on you. Your readers, however, won’t want to know about every single complication. Both you and your readers will have a much easier time if you make some decisions about your focus:

Do you want to concentrate on causes or effects?

Which of your explanations are most and least compelling?

How can you emphasize the points that are most important to you?

Which relatively insignificant or irrelevant ideas can you omit?

Generating Ideas

For more strategies for generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

Find a Topic. What familiar situation would be informative or instructive to explore? This assignment leaves you the option of writing from what you know, what you can find out, or a combination of the two. Begin by letting your thoughts wander over the results of a particular situation. Has the situation always been this way? Or has it changed in the last few years? Have things gotten better or worse?

When your thoughts begin to percolate, jot down likely topics. Then choose the idea that you care most about and that promises to be neither too large nor too small. A paper confined to the causes of a family’s move from New Jersey to Montana might be a single sentence: “My father’s company transferred him.” But the subsequent effects of the move on the family might become an interesting essay. On the other hand, you might need hundreds of pages to study all the effects of gangs in urban high schools. Instead, you might select just one unusual effect, such as gang members staking out territory in the parking lot of a local school.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

Has a difficult situation resulted from a change in your life (a lost job or a new one; a fluctuation in income; personal or family upheaval following death, divorce, accident, illness, or good fortune; a new school)?

Has the environment changed (due to a drought, a flood or a storm, a fire, a new industry, the collapse of an old industry)?

Has a disturbing situation been caused by an invention (the tablet, the e-reader, social-media platforms, the smartphone)?

Do certain employment trends cause you concern (for women in management, for young people in rural areas, for men in nursing)?

Is a situation on campus or in your neighborhood, city, or state causing problems for you (traffic, housing, access to healthy food, health care)?

Learning by Doing Determining Causes and Effects

Learning by Doing Determining Causes and Effects

Determining Causes and Effects

Working by yourself, determine the cause and effect of each of these situations:

Because Taylor studied, she earned an A on her test.

Due to the lack of rainfall in Texas, water restrictions are in effect.

Janine was injured in a roller derby bout because she was not wearing all her safety equipment.

Although Austin had parked for only five minutes in a handicapped parking spot, he received a ticket because he didn’t have the required placard.

Because Denmark’s homes and businesses are powered solely by wind, its residents enjoy a lower cost of energy.

List Causes and Effects. After noting causes and effects, consider which are immediate (evident and close at hand), which are remote (underlying, more basic, or earlier), and how you might arrange them in a logical sequence or causal chain.

| Focus on Causal Chain | ||||||||

| Remote Causes | → | Immediate Causes | → | Situation | → | Immediate Effects | → | Remote Effects |

| Foreign competition | → | Sales, profits drop | → | Clothing factory closing | → | Jobs vanish | → | Town flounders |

For more on thinking critically, see Ch. 3.

Once you figure out the basic causal relationships, focus on complexities or implications. Probe for contributing, related, or even hidden factors. As you draft, these ideas will be a rich resource, allowing you to focus on the most important causes or effects and to skip any that are minor.

| Focus on Immediate Effects | Focus on Remote Effects | ||

| Factory workers lose jobs | → | Households curtail spending | Town economy undermined |

| Grocery and other stores suffer | → | Businesses fold | Food pantry, social services overwhelmed |

| Workers lose health coverage | → | Health needs ignored | Hospital limits services and doctors leave |

| Retirees fear benefits lost | → | Confidence erodes | Unemployed and young people leave |

Learning by Doing Making a Cause-and-Effect Table

Learning by Doing Making a Cause-and-Effect Table

Making a Cause-and-Effect Table

Use the Table menu in your word processor or draw on paper a four-column table to help you assess the importance of causes and effects. Divide up your causes and effects, making entries under each heading. Refine your table as you relate, order, or limit your points.

| Major Cause | Minor Cause | Major Effect | Minor Effect |

For advice on finding a few pertinent sources, see section B in the Quick Research Guide.

Consider Sources of Support. After identifying causes and effects, note your evidence next to each item. You can then see at a glance exactly where you need more material. Star or underline any causes and effects that stand out as major ones. Ask, How significant is this cause? Would the situation not exist without it? (This major cause deserves a big star.) Or would the situation have arisen without it, for some other reason? (This minor cause might still matter but be less important.) Has this effect had a resounding impact? How much detail do you need to give about the results?

As you set priorities—identifying major causes or effects and noting missing information—you may wish to talk with others, use a search engine, or browse the library Web site for sources of supporting ideas, details, and statistics. You might look for illustrations of the problem, accounts of comparable situations, or charts showing current data and projections.

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

Read Choi's complete essay. For more about informal outlines, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

Start with a Scratch Outline and Thesis. Yun Yung Choi’s “Invisible Women” follows a clear plan based on a brief scratch outline that simply lists the effects of the change:

Intro—Personal anecdote

–Tie with Korean history

–Then add working thesis: The turnabout for women resulted from the influence of Confucianism in all aspects of society.

Comparison and contrast of status of women before and after Confucianism

Effects of Confucianism on women

Confinement

Little education

Loss of identity in marriage

No property rights

Conclusion: Impact still evident in Korea today but some hints of change

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

The paper makes its point: it identifies Confucianism as the reason for the status of Korean women and details four specific effects of Confucianism on women in Korean society. And it shows that cause and effect are closely related: Confucianism is the cause of the change in the status of Korean women, and Confucianism has had specific effects on Korean women.

Organize to Show Causes and Effects to Your Audience. Your paper’s core—showing how the situation came about (the causes), what followed as a result (the effects), or both—likely will follow one of these patterns:

| I. The situation | I. The situation | I. The situation |

| II. Its causes | II. Its effects | II. Its causes |

| III. Its effects |

Try planning by grouping causes and effects, then classifying them as major or minor. If you are writing about why more students accumulate credit-card debt now than a generation ago, you might list the following:

available credit for students

high credit limits and interest

reduced or uncertain income

excessive buying

On reflection you might decide that available credit, credit limits, and interest rates are determined by the credit card industry, government regulation, and current economic conditions. These factors certainly affect students, but you are more interested in causes and effects that individual students might be able to influence in order to minimize their debt. You consider whether your own growing debt is due to too little income or too many expenses. You could then organize the causes from least to most important, giving the major one more space and the final place. When your plan seems logical, discuss it or share a draft with a classmate, a friend, or your instructor. Ask whether your organization will make sense to someone else.

Introduce the Situation. Begin your draft by describing the situation you want to explain in no more than two or three paragraphs. Tell readers your task—explaining causes, effects, or both. Instead of doing this in a flat, mechanical fashion (“Now I am going to explain the causes”), announce your task casually, as if you were talking to someone: “At first, I didn’t realize that keeping six pet cheetahs in our backyard would bother the neighbors.” Or tantalize your readers as one writer did in a paper about her father’s sudden move to a Trappist monastery: “The real reason for Father’s decision didn’t become clear to me for a long while.”

Learning by Doing Focusing Your Introduction

Learning by Doing Focusing Your Introduction

Focusing Your Introduction

Read aloud the draft of your introduction for a classmate or small group, or post it for online discussion. Ask your readers first to identify where you state the main point of your essay—why you are explaining causes or effects. Then ask them to share their observations about the clarity of that statement or about any spots where your introduction bogs down in detail or skips over essentials.

For more on using sources for support, see Ch. 12 or the Quick Research Guide.

Work in Your Evidence. Some writers want to rough out a cause-and-effect draft, positioning all the major points first and then circling back to pull in supporting explanations and details. Others want to plunge deeply into each section—stating the main point, elaborating, and working in the evidence all at once. Tables, charts, and graphs can often consolidate information that substantiates or illustrates causes or effects. Place any graphics near the related text discussion, supporting but not duplicating it.

Revising and Editing

For more revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

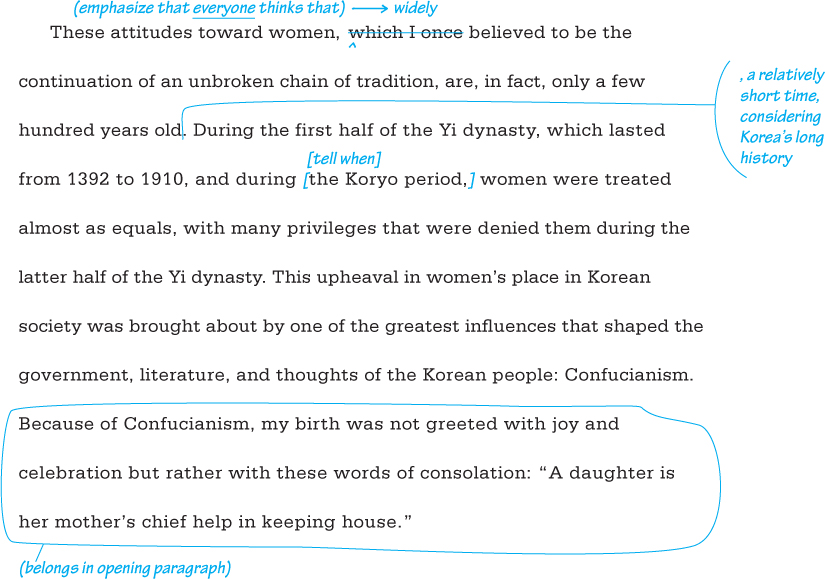

Because explaining causes and effects takes hard thought, set aside plenty of time for rewriting. As Yun Yung Choi approached her paper’s final version, she wanted to rework her thesis for greater precision with more detail.

| WORKING THESIS | The turnabout for women resulted from the influence of Confucianism in all aspects of society. |

| REVISED THESIS | This turnabout in women’s place in Korean society was brought about by one of the greatest influences that shaped the government, literature, and thoughts of the Korean people—Confucianism. |

Taking a cue from Choi, ask yourself the following questions about your thesis when you revise any cause-and-effect paper.

THESIS CHECKLIST

Is the purpose of your cause-and-effect analysis clear from your thesis? Is thesis (and the rest of the paper) focused on this purpose?

Could thesis be more specific about the causes or effects you will be discussing?

Could you make thesis more compelling based on details that you gathered while planning, drafting, or developing your essay?

Choi also faced a problem pointed out by classmates: how to make a smooth transition from recalling her own experience to probing causes.

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Explaining Causes and Effects

Peer Response Explaining Causes and Effects

Explaining Causes and Effects

Have a classmate or friend read your draft, considering how you’ve analyzed causes or effects. Ask your peer editor to answer questions such as the following:

For an explanation of causes:

Does the writer explain, rather than merely list, causes?

Do the causes seem logical and possible?

Are there other causes that the writer might consider? If so, list them.

For an explanation of effects:

Do all the effects seem to be results of the situation the writer describes?

Are there other effects that the writer might consider? If so, list them.

For all cause-and-effect papers:

What is the writer’s thesis? Does the explanation of causes or effects help the writer accomplish the purpose of the essay?

Is the order of supporting ideas clear? Can you suggest a better organization?

Are you convinced by the writer’s logic? Do you see any logical fallacies?

Are any causes or effects hard to accept?

Do the writer’s evidence and detail convince you? Put stars where more or better evidence is needed.

If this paper were yours, what is the one thing you would be sure to work on before handing it in?

REVISION CHECKLIST

Have you shown your readers your purpose in presenting causes or effects?

Is your explanation thoughtful, searching, and reasonable?

Where might you need to reorganize or add transitions so your paper is easy for readers to follow?

If you are tracing causes,

Have you made it clear that you are explaining causes?

Do you need to add any significant causes?

For more on evidence, see Assemble Supporting Evidence in Ch. 9. For more on mistakes in thinking called logical fallacies, see Learning by Writing in Ch. 9.

At what points might you need to add more evidence to convince readers that the causal relationships are valid, not just guesses?

Do you need to drop any remote causes you can’t begin to prove? Or any assertions made without proof?

Have you oversimplified by assuming that only one small cause accounts for a large outcome or that one thing caused another just by preceding it?

If you are determining effects,

Have you made it clear that you are explaining effects?

What possible effects have you left out? Are any of them worth adding?

At what points might you need more evidence that the effects occurred?

Could any effect have resulted not from the cause you describe but from some other cause?

For more on editing and proofreading strategies, see Editing and Proofreading in Ch. 23.

After you have revised your cause-and-effect essay, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems you find.

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide and Quick Format Guide.