1.4The Genomic Revolution Is Transforming Biochemistry, Medicine, and Other Fields

The Genomic Revolution Is Transforming Biochemistry, Medicine, and Other Fields

Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA suggested the hypothesis that hereditary information is stored as a sequence of bases along long strands of DNA. This remarkable insight provided an entirely new way of thinking about biology. However, at the time that it was made, Watson and Crick’s discovery, though full of potential, remained to be confirmed and many features needed to be elucidated. How is the sequence information read and translated into action? What are the sequences of naturally occurring DNA molecules and how can such sequences be experimentally determined? Through advances in biochemistry and related sciences, we now have essentially complete answers to these questions. Indeed, in the past decade or so, scientists have determined the complete genome sequences of hundreds of different organisms, including simple microorganisms, plants, animals of varying degrees of complexity, and human beings. Comparisons of these genome sequences, with the use of methods introduced in (Chapter 6), have been sources of many insights that have transformed biochemistry. In addition to its experimental and clinical aspects, biochemistry has now become an information science.

Genome sequencing has transformed biochemistry and other fields

The sequencing of a human genome was a daunting task because it contains approximately 3 billion (3 × 109) base pairs. For example, the sequence

ACATTTGCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGCAACCTCAAACAGACACCATGGTGCATCTGACTCCTGAGGAGAAGTCTGCCGTTACTGCCCTGTGGGGCAAGGTGAACGTGGA…

is a part of one of the genes that encodes hemoglobin, the oxygen carrier in our blood. This gene is found on the end of chromosome 9 of our 24 distinct chromosomes. If we were to include the complete sequence of our entire genome, this chapter would run to more than 500,000 pages. The sequencing of our genome is truly a landmark in human history. This sequence contains a vast amount of information, some of which we can now extract and interpret, but much of which we are only beginning to understand. For example, some human diseases have been linked to particular variations in genomic sequence. Sickle-

18

Determining the first human genome sequences was a great challenge. It required the efforts of large teams of geneticists, molecular biologists, biochemists, and computer scientists, as well as billions of dollars, because there was no previous framework for aligning the sequences of various DNA fragments. One human genome sequence can serve as a reference for other sequences. The availability of such reference sequences enables much more rapid characterization of partial or complete genomes from other individuals. As we will discuss in (Chapter 5), arrays containing millions of target single-

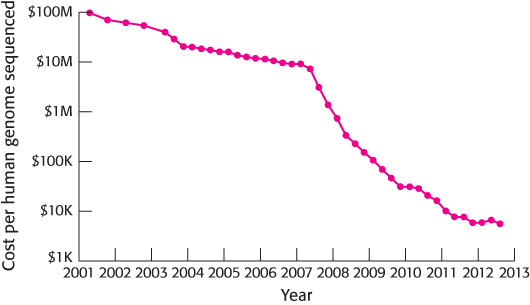

Methods for sequencing DNA have also been improving rapidly, driven by a deep understanding of the biochemistry of DNA replication and other processes. This has resulted in both dramatic increases in the DNA sequencing rate and decreases in cost (Figure 1.19). The availability of such powerful sequencing technology is transforming many fields, including medicine, dentistry, microbiology, pharmacology, and ecology, although a great deal remains to be done to improve the accuracy and precision of the interpretation of these large genomic and related data sets.

Each person has a unique sequence of DNA base pairs. How different are we from one another at the genomic level? Examination of genomic variation reveals that, on average, each pair of individuals has a different base in one position per 200 bases; that is, the difference is approximately 0.5%. This variation between individuals who are not closely related is quite substantial compared with differences in populations. The average difference between two people within one ethnic group is greater than the difference between the averages of two different ethnic groups.

The significance of much of this genetic variation is not understood. As noted earlier, variation in a single base within the genome can lead to a disease such as sickle-

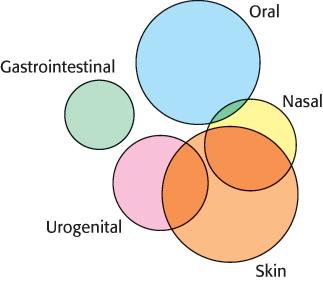

Our own genes are not the only ones that can contribute to health and disease. Our bodies, including our skin, mouth, digestive tract, genitourinary tract, respiratory tract, and other areas, contain large number of microorganisms. These complex communities have been characterized through powerful methods that allow DNA isolated from these biological samples to be sequenced without any previous knowledge of the organisms present. Many of these organisms had not previously been discovered because they can only grow as part of complex communities and thus cannot be isolated through standard microbiological techniques. Remarkably, it appears that we are outnumbered in our own bodies! Each of us contains approximately ten times more microbials cells than human cells and these microbial cells include many more genes than do our own genomes. These microbiomes differ from site to site, from one person to another and over time in the same individual. They appear to play roles in health and in diseases such as obesity and dental caries (Figure 1.20).

19

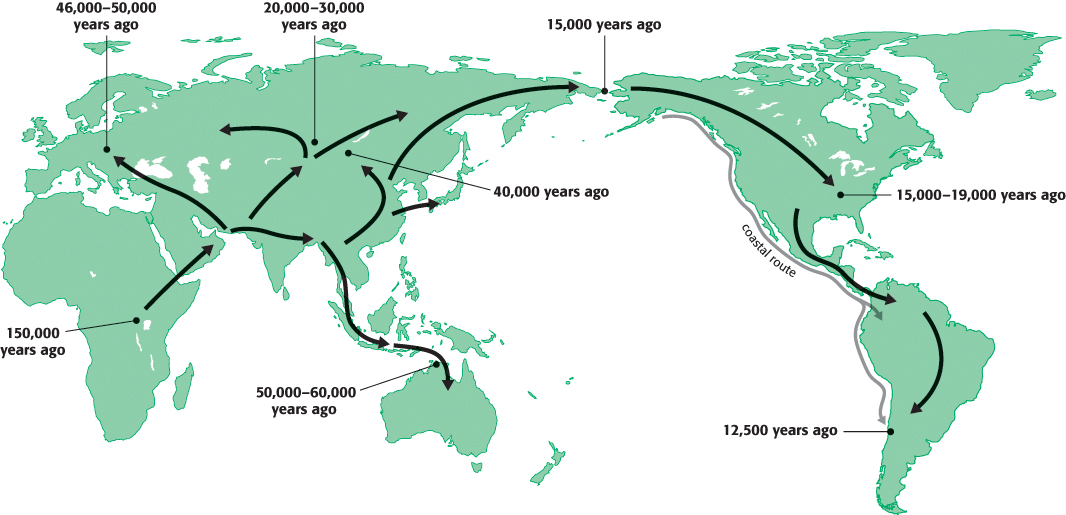

In addition to the implications for understanding human health and disease, the genome sequence is a source of deep insight into other aspects of human biology and culture. For example, by comparing the sequences of different individuals and populations, we can learn a great deal about human history. On the basis of such analysis, a compelling case can be made that the human species originated in Africa, and the occurrence and even the timing of important migrations of groups of human beings can be demonstrated (Figure 1.21). Finally, comparisons of the human genome with the genomes of other organisms are confirming the tremendous unity that exists at the level of biochemistry and are revealing key steps in the course of evolution from relatively simple, single-

20

Environmental factors influence human biochemistry

Although our genetic makeup (and that of our microbiomes) is an important factor that contributes to disease susceptibility and to other traits, factors in a person’s environment also are significant. What are these environmental factors? Perhaps the most obvious are chemicals that we eat or are exposed to in some other way. The adage “you are what you eat” has considerable validity; it applies both to substances that we ingest in significant quantities and to those that we ingest in only trace amounts. Throughout our study of biochemistry, we will encounter vitamins and trace elements and their derivatives that play crucial roles in many processes. In many cases, the roles of these chemicals were first revealed through investigation of deficiency disorders observed in people who do not take in a sufficient quantity of a particular vitamin or trace element. Despite the fact that the most important essential dietary factors have been known for some time, new roles for them continue to be discovered.

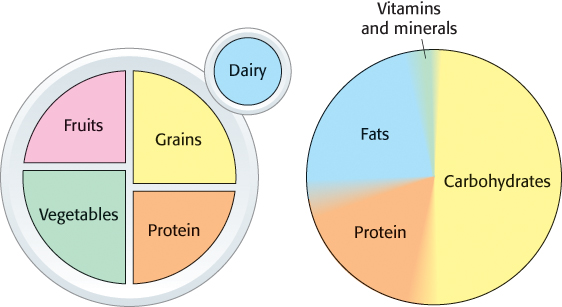

A healthful diet requires a balance of major food groups. In addition to providing vitamins and trace elements, food provides calories in the form of substances that can be broken down to release energy that drives other biochemical processes. Proteins, fats, and carbohydrates provide the building blocks used to construct the molecules of life (Figure 1.22). Finally, it is possible to get too much of a good thing. Human beings evolved under circumstances in which food, particularly rich foods such as meat, was scarce. With the development of agriculture and modern economies, rich foods are now plentiful in parts of the world. Some of the most prevalent diseases in the so-

Chemicals are only one important class of environmental factors. Our behaviors also have biochemical consequences. Through physical activity, we consume the calories that we take in, ensuring an appropriate balance between food intake and energy expenditure. Activities ranging from exercise to emotional responses such as fear and love may activate specific biochemical pathways, leading to changes in levels of gene expression, the release of hormones, and other consequences. Furthermore, the interplay between biochemistry and behavior is bidirectional. Just as our biochemistry is affected by our behavior, so, too, our behavior is affected, although certainly not completely determined, by our genetic makeup and other aspects of our biochemistry. Genetic factors associated with a range of behavioral characteristics have been at least tentatively identified.

Just as vitamin deficiencies and genetic diseases have revealed fundamental principles of biochemistry and biology, investigations of variations in behavior and their linkage to genetic and biochemical factors are potential sources of great insight into mechanisms within the brain. For example, studies of drug addiction have revealed neural circuits and biochemical pathways that greatly influence aspects of behavior. Unraveling the interplay between biology and behavior is one of the great challenges in modern science, and biochemistry is providing some of the most important concepts and tools for this endeavor.

21

Genome sequences encode proteins and patterns of expression

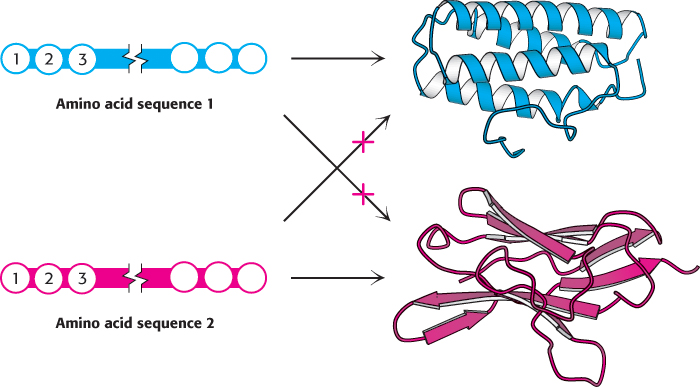

The structure of DNA revealed how information is stored in the base sequence along a DNA strand. But what information is stored and how is it expressed? The most fundamental role of DNA is to encode the sequences of proteins. Like DNA, proteins are linear polymers. However, proteins differ from DNA in two important ways. First, proteins are built from 20 building blocks, called amino acids, rather than just four, as in DNA. The chemical complexity provided by this variety of building blocks enables proteins to perform a wide range of functions. Second, proteins spontaneously fold into elaborate three-

The fundamental unit of hereditary information, the gene, is becoming increasingly difficult to precisely define as our knowledge of the complexities of genetics and genomics increases. The genes that are simplest to define encode the sequences of proteins. For these protein-

On the basis of current knowledge, the protein-

22