2.4Tertiary Structure: Water-Soluble Proteins Fold into Compact Structures with Nonpolar Cores

Tertiary Structure: Water-Soluble Proteins Fold into Compact Structures with Nonpolar Cores

Let us now examine how amino acids are grouped together in a complete protein. X-

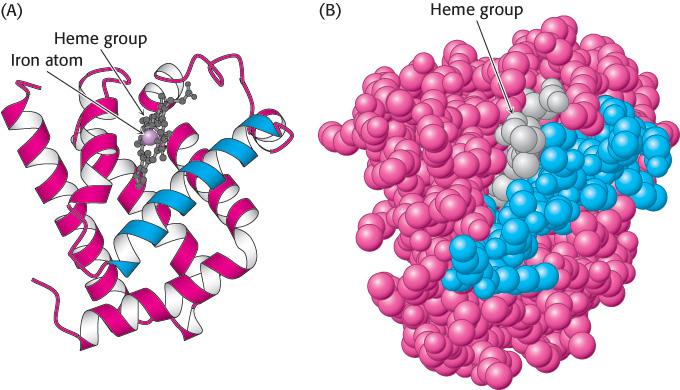

Myoglobin, the oxygen storage protein in muscle, is a single polypeptide chain of 153 amino acids (Chapter 7). The capacity of myoglobin to bind oxygen depends on the presence of heme, a nonpolypeptide prosthetic (helper) group consisting of protoporphyrin IX and a central iron atom. Myoglobin is an extremely compact molecule. Its overall dimensions are 45 × 35 × 25 Å, an order of magnitude less than if it were fully stretched out (Figure 2.43). About 70% of the main chain is folded into eight α helices, and much of the rest of the chain forms turns and loops between helices.

FIGURE 2.43 Three-

FIGURE 2.43 Three-The folding of the main chain of myoglobin, like that of most other proteins, is complex and devoid of symmetry. The overall course of the polypeptide chain of a protein is referred to as its tertiary structure. A unifying principle emerges from the distribution of side chains. Strikingly, the interior consists almost entirely of nonpolar residues such as leucine, valine, methionine, and phenylalanine (Figure 2.44). Charged residues such as aspartate, glutamate, lysine, and arginine are absent from the inside of myoglobin. The only polar residues inside are two histidine residues, which play critical roles in binding iron and oxygen. The outside of myoglobin, on the other hand, consists of both polar and nonpolar residues. The space-

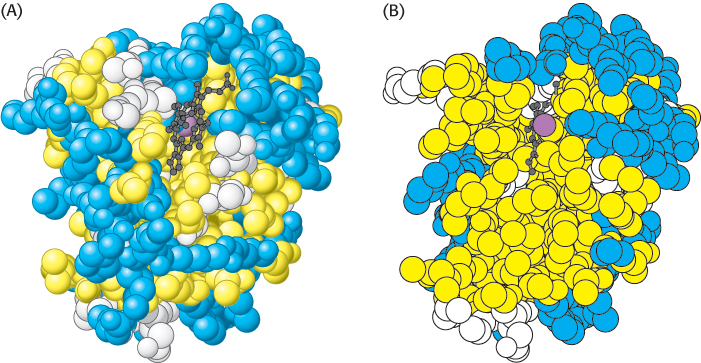

FIGURE 2.44 Distribution of amino acids in myoglobin. (A) A space-

FIGURE 2.44 Distribution of amino acids in myoglobin. (A) A space-47

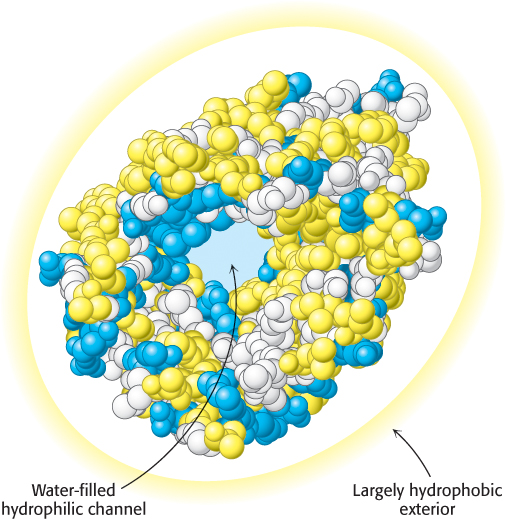

FIGURE 2.45 “Inside out” amino acid distribution in porin. The outside of porin (which contacts hydrophobic groups in membranes) is covered largely with hydrophobic residues, whereas the center includes a water-

FIGURE 2.45 “Inside out” amino acid distribution in porin. The outside of porin (which contacts hydrophobic groups in membranes) is covered largely with hydrophobic residues, whereas the center includes a water-This contrasting distribution of polar and nonpolar residues reveals a key facet of protein architecture. In an aqueous environment, protein folding is driven by the strong tendency of hydrophobic residues to be excluded from water. Recall that a system is more thermodynamically stable when hydrophobic groups are clustered rather than extended into the aqueous surroundings. The polypeptide chain therefore folds so that its hydrophobic side chains are buried and its polar, charged chains are on the surface. Many α helices and β strands are amphipathic; that is, the α helix or β strand has a hydrophobic face, which points into the protein interior, and a more polar face, which points into solution. The fate of the main chain accompanying the hydrophobic side chains is important, too. An unpaired peptide NH or CO group markedly prefers water to a nonpolar milieu. The secret of burying a segment of main chain in a hydrophobic environment is to pair all the NH and CO groups by hydrogen bonding. This pairing is neatly accomplished in an α helix or β sheet. Van der Waals interactions between tightly packed hydrocarbon side chains also contribute to the stability of proteins. We can now understand why the set of 20 amino acids contains several that differ subtly in size and shape. They provide a palette from which to choose to fill the interior of a protein neatly and thereby maximize van der Waals interactions, which require intimate contact.

Some proteins that span biological membranes are “the exceptions that prove the rule” because they have the reverse distribution of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids. For example, consider porins, proteins found in the outer membranes of many bacteria (Figure 2.45). Membranes are built largely of hydrophobic alkane chains (Section 12.2). Thus, porins are covered on the outside largely with hydrophobic residues that interact with the neighboring alkane chains. In contrast, the center of the protein contains many charged and polar amino acids that surround a water-

48

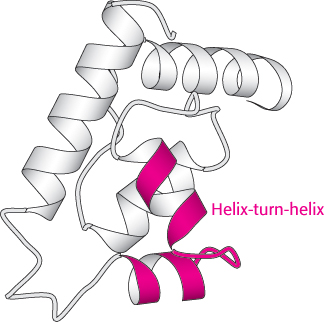

Certain combinations of secondary structure are present in many proteins and frequently exhibit similar functions. These combinations are called motifs or supersecondary structures. For example, an α helix separated from another α helix by a turn, called a helix-

FIGURE 2.46 The helix-

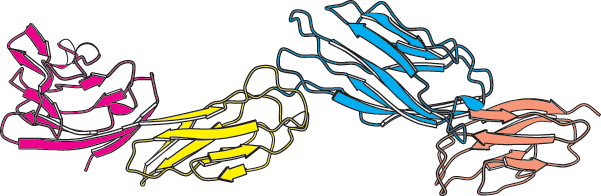

FIGURE 2.46 The helix-Some polypeptide chains fold into two or more compact regions that may be connected by a flexible segment of polypeptide chain, rather like pearls on a string. These compact globular units, called domains, range in size from about 30 to 400 amino acid residues. For example, the extracellular part of CD4, a protein on the surface of certain cells of the immune system (Section 34.4), comprises four similar domains of approximately 100 amino acids each (Figure 2.47). Proteins may have domains in common even if their overall tertiary structures are different.

FIGURE 2.47 Protein domains. The cell-

FIGURE 2.47 Protein domains. The cell-